Etain Tannam, from Trinity College Dublin, gives her first impressions on the UK Position Paper on Northern Ireland and Ireland. She contends that while it represents a cross-cutting consensus on certain aspects of the Irish border (including the Good Friday Agreement), it is vague about exactly how the border will be managed and it seems to attempt to link resolving the border issue with EU agreement to the UK’s trade preferences.

The UK position paper issued on 16 August deals with 4 key issues systematically ( if not always in great depth): upholding the Good Friday Agreement, maintaining the Common Travel Area (CTA), avoiding a hard border for movement of goods and preserving North-South and East-West cooperation, including in energy. It calls for Irish citizens in Northern Ireland to continue to have EU citizens’ rights. It praises the EU’s support for the peace process in Northern Ireland, through EU Peace Funds and calls for Peace funding to continue post-Brexit. The language used echoes the logic and rationale of the Good Friday Agreement and the paper highlights identity as being at the heart of divisions in Northern Ireland, rather than reverting to sole reliance on ‘technical’ solutions, or absolutist arguments. The paper proposes that there be no customs posts on the border and argues that small scale businesses should be allowed trade freely, but that larger ones would be subject to monitoring, thus attempting to respond to fundamental fear felt by many living along the border who rely on trade and travel for their livelihood, as well as needing cross-border access to hospitals and ambulance services. Similarly, the paper emphasises protecting a single energy market on the island (to lower energy costs), viewed as essential for businesses.

some aspects of the paper reflect Irish governmental preferences

Overall, some aspects of the paper reflect Irish governmental preferences. In particular, the UK government’s opposition to customs posts was welcomed by the Irish foreign minister Simon Coveney, although the UK position paper, supporting unionist preferences, did rule out the Irish foreign minister’s earlier call for a sea border between Northern Ireland, Ireland and Britain (and the idea was later revoked by the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar). Similarly, the emphasis of the paper on the border issue as being a political issue with implications for identity and of the centrality of the Good Friday Agreement, will no doubt be welcomed by the Irish government. Indeed, the Irish government and its diplomats have been lobbying EU and UK officials to emphasise the fundamentally political nature of the border and its high sensitivity, rather than it being a technical issue.

Of course, apart from the Irish government’s role in the Good Friday Agreement, Ireland, as an EU state has a veto in the EU-UK negotiations over moving to the next stage of Brexit negotiations, so its influence in UK policy towards Northern Ireland in the Brexit negotiations is significant. In addition, the EU recognised Northern Ireland as one of the top 3 priorities in the Brexit negotiations in large part because of intensive Irish lobbying and because of EU recognition that the EU supported Northern Ireland’s peace process financially and is committed to peace. The negotiating schedule is that Northern Ireland, citizens’ rights and the Brexit ‘bill’ will be dealt with first and then if progress is made, negotiations will move to the second stage, where customs will be negotiated. The UK government’s preference was to deal with the customs issue and the other 3 issues simultaneously, so a key Irish government and EU concern has been that the UK government will attempt to link the Northern Ireland issue to the customs issue, thus dealing with both issues simultaneously, not according to the EU schedule. In this way, Northern Ireland would become a bargaining chip for the UK.

Indeed, the position paper follows its list of criteria for future border arrangements with a section on various customs scenarios to help achieve those criteria. In other words, the Northern Ireland issue is being clearly linked in the paper to customs negotiations. Thus, the Irish government, in response to the position paper stated that unless progress is made on Northern Ireland, Brexit negotiations will not continue to the next phase – customs.

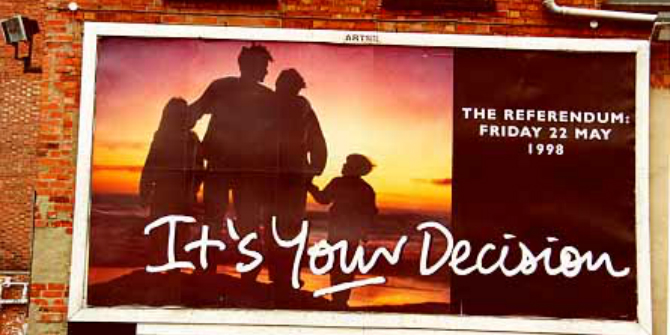

Referenda in Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland, Friday 22 May 1998. Image: Public Domain.

Referenda in Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland, Friday 22 May 1998. Image: Public Domain.

Therefore, the position paper represents a cross-cutting consensus on some general points. However, it is vague about exactly how the border will be managed and it tends to set out aspirations (for example, paragraphs 44, 45). There are huge issues of, for example, how to prevent smuggling, how to ensure food safety standards and quality control, how to manage terrorism between a state in the EU bordering one outside and these are not tackled adequately. If the UK were to be in a Customs Union with the EU, many of the issues would be resolved, but in the absence of this, the current plan fails to deal with very large problems and appears to link Northern Ireland’s future to the UK receiving the perks of a customs unions, without the obligations. The EU will be willing to seek a bespoke arrangement for Northern Ireland, but it will be firmly opposed to any UK attempt to link the two issues. It is noticeable that the Irish government’s response emphasises that there are ‘unanswered questions’. As always, the devil is in the detail.

*Thanks to Ben Tonra for guiding me on Ireland’s veto power in the Brexit negotiations.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Brexit blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Etain Tannam is Assistant Professor in International Peace Studies, Trinity College Dublin and Associate P.I. Trinity’s Long Room Hub for Arts and Humanities, Trinity College Dublin.