How did the leaflets circulated before the EU referendum talk about migrants? Alexandra Bulat (UCL SSEES) examines the LSE’s collection and finds – on both sides – a distinction between ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ migrants, whether from within or outside the EU. At no point were the views of the migrants themselves heard.

How did the leaflets circulated before the EU referendum talk about migrants? Alexandra Bulat (UCL SSEES) examines the LSE’s collection and finds – on both sides – a distinction between ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ migrants, whether from within or outside the EU. At no point were the views of the migrants themselves heard.

Researchers agree that immigration, alongside economics, were the top two issues for campaigners and voters alike during the EU referendum. But the rapidly emerging literature on Brexit lacks a detailed analysis on the nature of immigration arguments. Apart from brief references to campaign material and some discussion around the official government EU referendum leaflet (for instance, in a recent book by Andrew Glencross), there is not much analysis of ephemera as a form through which ideas and arguments about immigration were communicated.

Yet millions of leaflets were distributed during the campaign on high streets, in neighbourhoods, at events across the country, by post, and by other means. Usually, these leaflets summarise a campaigner’s key arguments, with more detail presented through other media, such as televised interviews, debates, and campaign websites.

Fully 40% of the 177 individual digitised items in the LSE Brexit collection of referendum ephemera mentioned immigration. The sample details are available here. What types of people were mentioned, and what arguments were made?

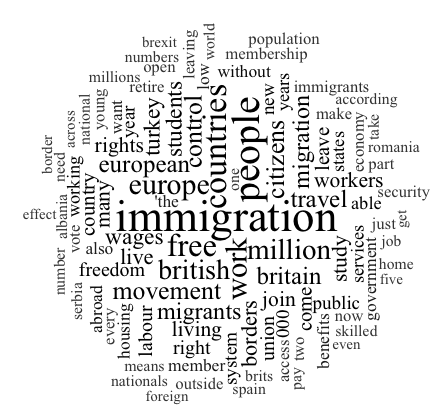

As you would expect in a referendum on the UK’s continuing EU membership, most content is about freedom of movement within the EU, comprising over two-thirds of the total. The remaining third is about non-EU migration, including references to Commonwealth migration, but also ‘future EU migration’ (such as from Turkey). There are a few references to refugees and asylum seekers (described as migrants too), and also terrorists.

However, there are also mentions of EU students and researchers, NHS professionals, framed in what Jürgen Habermas identifies as a different type of utilitarian frame – namely economic prosperity. Those arguments emphasise the contributions made by migrants and the need for migrant workers. EU students and researchers are also mentioned within the context of multiculturalism, with Remain campaigners supporting ‘an international, outward looking culture’ (a leaflet by Universities for Europe), as opposed to a nationalistic stance discouraging this diversity. ‘The brightest and the best’ migrants, as one of the leaflet’s headlines reads, were praised by Remain campaigners, but ‘the rest’ were left to be criticised in their adversaries’ campaign materials.

Meanwhile, in the same debate about freedom of movement, references to British people were almost entirely positive. Remain campaigners stressed the benefits of free movement for UK citizens who wish to ‘travel, work, study, and retire in the EU, without visas’ (a leaflet by Wales Stronger In Europe). The official national Remain campaign insisted that freedom of movement was ‘great for pensioners’, ‘great for young people’ and ‘great for holidaymakers’ (Image 3). It perhaps failed to recognise that those groups (British retirees living abroad, students and younger people, and those who travel frequently) did not necessarily represent key voters who needed much persuasion to vote Remain.

Moreover, some Leave campaigners insisted that the rights of British citizens living in other EU states will not change after Brexit. ‘If we left the EU would we still be able to travel, take holidays, work, study and own property in Europe?’, asks a detailed FAQ-style leaflet from the UK Independence Party. ‘Britons were able to do all these things long before we joined the EU, and we will be able to do them after we leave’, the answer reads. These assurances are of little use now to British people abroad (and also EU citizens in the UK) who feel a great deal of uncertainty about the outcome of the Brexit negotiations on their future rights.

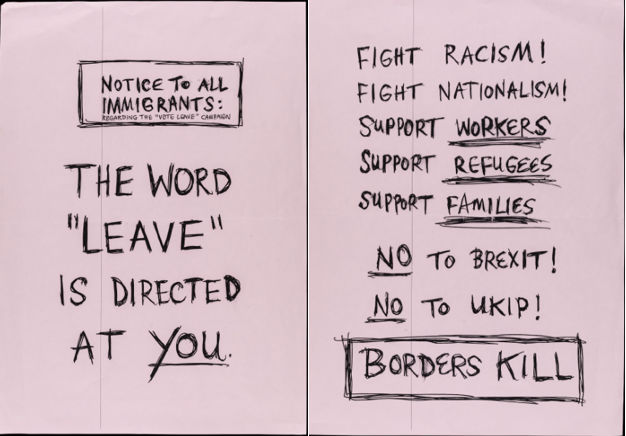

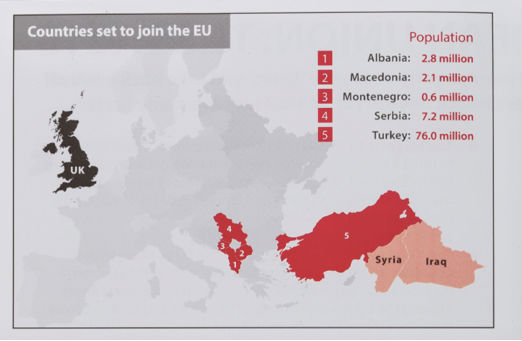

Apart from freedom of movement, the leaflets spoke about non-EU migration and refugees. There are two contrasting portrayals. One is the image of migrants within a security frame. Taking for granted that the EU would expand – including frequent mentions of Turkey joining the EU (e.g. Image 4) – this depiction plays into security fears of another wave of mass migration, but also the increased risk of terrorism in the UK. The security frame comes with the ‘solution’: the UK needs to control its borders by voting to Leave.

The positive case for non-EU migration is about the Commonwealth. Leave campaigners criticise an unfair immigration system giving preference to ‘low-skilled’ EU migrants over highly qualified ‘Commonwealth friends’.

Overall, two observations apply to all migration-related leaflets: the obsession with the scale of migration and the lack of migrants as sources. Despite the fact that the UK’s EU migration figures are based on estimates (usually passenger survey data) and they are not exact numbers of people coming to and leaving the UK, leaflets on both sides claim precise numbers of different types of migrants. This leads to various figures being communicated by different campaigners when describing the same type of migration. Leave campaigners use different time frames (e.g. migration since 2004) to speak about EU migration as ‘equivalent to a city the size of’ (e.g. Manchester, Newcastle, York), depending on where the leaflet is distributed. Lastly, on sources, although quotes from experts and members of the public are employed in some leaflets, both sides failed to include opinions from EU migrant organisations or the non-UK EU residents themselves. This suggests ‘EU migrants’ were spoken for and, in addition to not having a say at the ballot box, did not have their own voice in the campaign leaflets which made claims about them.

Cherrypicking different types of migrants to suit pre-existing arguments created a selective debate, which was unfair for the migrant population as a whole. Three main categories emerge from the leaflets. First, there is ‘us’, British-born people, some of whom are believed to benefit from free movement. Second, there are ‘desirable’ migrations, such as the free movement of ‘the brightest and the best’ EU students and NHS workers contributing to the economy, from a Remain perspective, and high-skilled Commonwealth migration, from a Leave standpoint. Third, there is ‘the rest’, those ‘undesirable’ flows of people, such as ‘low-skilled Eastern Europeans’, for instance, or refugees (who are portrayed in an even more negative light). Who is included in the latter two categories very much depends on the agenda of the organisation publishing the leaflets.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Alexandra Bulat is an ESRC-funded research student at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES), University College London (UCL). Her doctoral research focuses on attitudes towards EU migration in Stratford (London) and Clacton-on-Sea. Alexandra tweets @alexandrabulat.

2 Comments