The right to move and work freely in the EU is a key point of contestation in the Brexit negotiations. But what effect will leaving the EU have on the ways and means in which EU migrants keep in touch with their relatives? Kathy Burrell (University of Liverpool) and Matt Badcock (Leeds Beckett University) explore the virtual and physical networks that EU enlargement enabled – especially the flights opened up by Open Skies – and the way they have shaped migrants’ decisions about where to live and work.

The right to move and work freely in the EU is a key point of contestation in the Brexit negotiations. But what effect will leaving the EU have on the ways and means in which EU migrants keep in touch with their relatives? Kathy Burrell (University of Liverpool) and Matt Badcock (Leeds Beckett University) explore the virtual and physical networks that EU enlargement enabled – especially the flights opened up by Open Skies – and the way they have shaped migrants’ decisions about where to live and work.

Brexit, even before it has happened, is a significant presence in the lives of EU nationals in the UK. At its most fundamental it has generated new worries about how easy it is going to be to stay in the UK afterwards. Then come uncertainties about more general future plans, family arrangements, work, housing and healthcare access – all tangled up in a sense of being rejected by the country you had started to call home.

But lurking behind these prominent issues are further vulnerabilities which are not immediately obvious. Not least is the impact Brexit could wreak on a series of ‘secondary mobilities’, the things which have made rich and plentiful transnational connections relatively accessible for EU nationals in the UK, and which have become central to many of the lives being lived here. Three types of secondary mobility may be under threat, and we consider these with Polish migrants in mind especially.

Virtual communication

Much has been made of the new (hyper)mobility regime within the EU, which was heralded by enlargement in 2004. No less important has been the accompanying technological revolution which has transformed the ways and ease of keeping in touch across long distances. Migrants no longer rely on ‘cheap calls’: they can text, Skype, FaceTime and connect through social media, such as Facebook, at little cost, more spontaneously, and for longer durations. What is worth noting about this ‘secondary mobility’ is that Brexit is unlikely to affect it too much; these developments largely sit outside of national and supranational frameworks. Notwithstanding any new increases in phone roaming charges after Brexit, a harder border arrangement with the EU should not have a major impact on virtual, communication mobilities.

Physical trips

If virtual secondary mobilities stay intact, what about the physical ones, reliant on the material structures of borders, ports and roads? While distance may still be crossed virtually, there may be new configurations in the corporeal journeys people make back and forth. Faced with new border arrangements, those qualitative experiences of travelling – passport queues, being quizzed about documentation – could become much more uncomfortable, and closer to those which current non-EU nationals endure.

And then there are the effects that new, as yet unclear, customs deals could have on car, coach and lorry travel and all the intercontinental cargomobilities (‘continental’ shops, courier services) EU enlargement has spawned and EU arrangements have governed. Concerns about how a port such as Dover will manage post-Brexit have wider implications for lives and livelihoods sustained through European road links. If the hope of new ‘frictionless’ customs e-borders does not materialise, the whole experience of travelling and transporting, as well as trading, could involve much more friction.

The liberalisation of air travel

Finally – and thinking about Polish migration in particular – perhaps the transnational connection most under threat is the dense low-cost airline infrastructure built up since the 2006 European Common Aviation Area (ECAA) treaty, a liberalising bilateral agreement which established a single market for European aviation services.

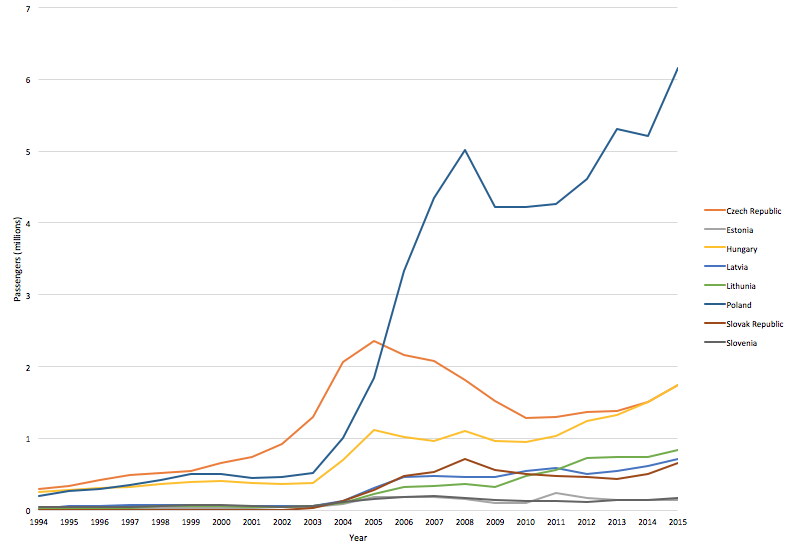

Figure 1: A8 countries/ UK passenger numbers, 1994-2015

Source: derived from CAA UK airport data

Crucially, this ‘Open Skies’ treaty allowed an airline from any ECAA member state to fly between any member state airport (the so-called ‘seventh freedom’), meaning that ‘foreign’ airlines could provide both domestic flights within another member country and international flights between any other two countries within the treaty zone. This development enabled low cost airlines such as Ryanair, easyJet and Wizz Air to expand, free from national and hub obligations. The significance for Polish/UK migration here is enormous. Most basically, there has been a clear correlation between migration from Poland to the UK and air passenger numbers in the period after 2004 (figure 1). While coach and car travel were key routes for migration journeys, air travel has become a hugely significant component of this new mobility.

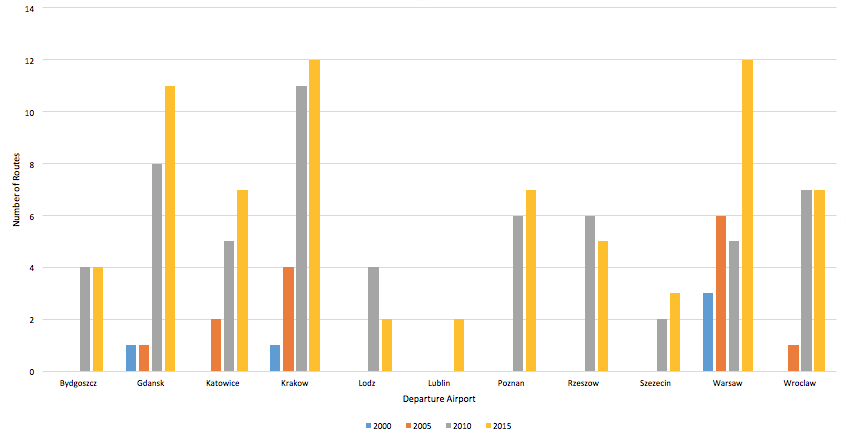

Figure 2: Number of UK destinations from Polish airports

Source: derived from CAA UK airport data

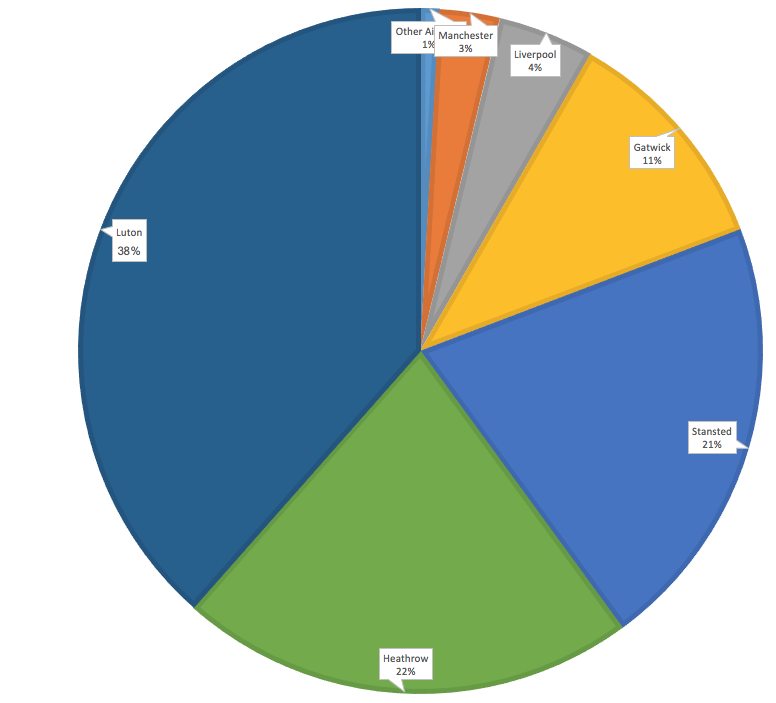

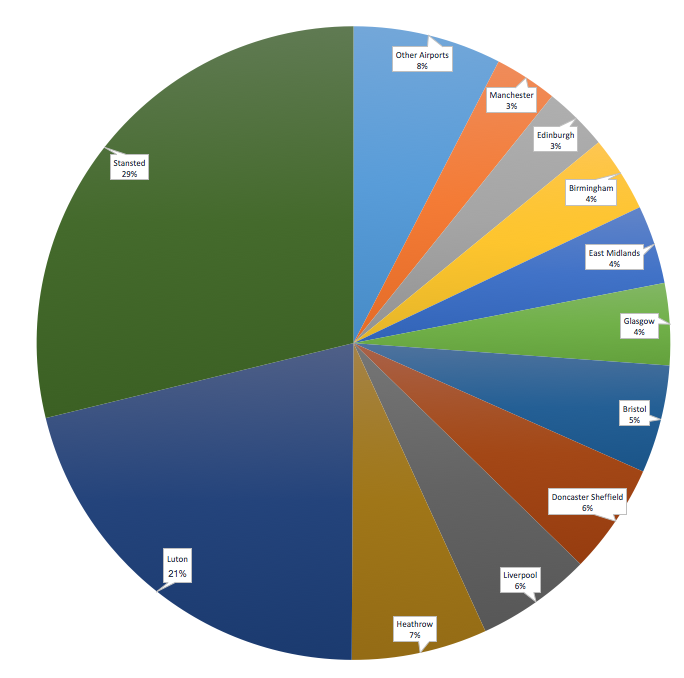

And, as a result of this new liberalisation and the demands of migration, the period since EU expansion has seen flight links between the two countries proliferate, creating a new regional geography of translocal routes, and a new infrastructure of mobility and migration. Regional airports in Poland have been transformed into international hubs (figure 2), with flights to the UK transporting migrants to an increasingly wide range of airports – not just those around London (figures 3 and 4). The latter trend has mirrored the very significant (and largely historically unprecedented for a migrant group) widespread settlement of Poles across the whole of the country.

Figure 3: Share of passengers to/from Poland through UK airports, 2005

Source: derived from CAA UK airport data

This is important because it has meant that migrating from Poland to the UK has become quicker, cheaper, and generally more convenient. While these low cost routes have created their own tensions, indignities and costs, translocal lives have been built with the help of this aviation infrastructure. You can fly between Doncaster and Katowice (Wizz Air), Birmingham and Bydgoszcz (Ryanair), reducing the practical distance between towns and cities in Poland and in the UK. Research has shown that this has mattered – it has figured in people’s decisions about where to migrate to, and how easily they can return for visits.

Figure 4: Share of passengers to/from Poland through UK airports, 2015

Source: derived from CAA UK airport data

Brexit brings real uncertainties for these connections. If the UK leaves the EU and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, it would also mean leaving the ECAA. At the moment there is no clarity on what a post-Brexit aviation deal would look like, and what it would mean for these low cost airlines especially. The implications for Ryanair, an Irish company offering the largest number of links between the UK and Poland, and with its main hub at Stansted, could be enormous; the airline could potentially lose its right to serve EU and ECAA countries from the UK. Doubts have already been raised by Ryanair about how much capacity it will devote to the UK market in the future because of the continuing uncertainty. Suddenly, some of those regional flight connections could look vulnerable.

Real and imaginative mobilities and distance

Kajsa Ellegård and Bertil Vilhelmson have argued that ‘the friction of distance is still of great importance for most people in daily life’. While none of these secondary mobilities are likely to impact on the fundamental legal rights and situations of EU nationals, the friction of distance is likely to be felt more keenly after Brexit for EU migrants living in the UK, and vice versa. It could jeopardise some of the relative ease of movement which has underpinned post-accession migration. And with this, there is the possibility that the emotional, imagined distance could increase too, for migrants who still want to connect back. Moreover, even if Brexit affects these secondary mobilities very little, it is apparent how much the mobility EU expansion afforded has been taken for granted. This migration has not happened in a vacuum – as well as being governed by legal and political landscapes, it has also been shaped by infrastructural developments and regulations. Brexit reminds us of the layered, intersectional and complex nature of migration and transnational connections, their fragility, and the social and emotional dynamics that are tied up with them.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Dr Kathy Burrell is a Senior Lecturer in Social and Cultural Geography at the University of Liverpool.

Dr Matt Badcock is Head of Sociology at Leeds Beckett University.

“ways and means in which EU migrants keep in touch with their relatives”

Use a visa like everyone else

I agree with JCantss

but getting Visa of every country is a tuff job.