Did hate crime spike after the referendum? While there is no doubt the number of reported crimes increased, they are always more frequent in June and July and after other significant events, like terror attacks. After controlling for these factors, Daniel Devine (University of Southampton) finds the referendum was associated with a statistically significant rise in hate crime. But how much, and what was it about the vote that had such a powerful effect?

Did hate crime spike after the referendum? While there is no doubt the number of reported crimes increased, they are always more frequent in June and July and after other significant events, like terror attacks. After controlling for these factors, Daniel Devine (University of Southampton) finds the referendum was associated with a statistically significant rise in hate crime. But how much, and what was it about the vote that had such a powerful effect?

Soon after the Leave vote, the United Nations’ committee on the elimination of racial discrimination argued that ‘British politicians helped fuel a steep rise in racist hate crimes during and after the EU referendum campaign’. Conservative Home disagreed, and the Daily Mail called it the ‘Great Brexit Hate Crime Myth’. The debate did not go away. As recently as October 2017, Labour MP Stella Creasy claimed there was ‘no doubt’ about Brexit’s impact, and German newspaper Deutsche Welle asked if the UK’s ‘racist hate crime problem is out of control’.

Despite this huge and polarised media coverage of an undeniably important topic, there was little, if any, rigorous analysis of this possibility. As The Spectator concluded:

Perhaps the referendum did lead to a rise in hate crime. Then again, perhaps it didn’t. But despite the angry reports blaming Brexit, the only thing that is clear is that there is little proof either way.

In a recent working paper, I have sought to answer precisely this question. In October 2017, the Home Office released data about the number of racial and religious hate crimes in England and Wales. Exceptionally, they released not only monthly data over a period of four years but also daily data over nearly two years. These include the referendum, but also significant terror attacks on UK and international soil. Because of the length of the time covered and quality of data available, it is possible to control for the random fluctuations and wider trends of hate crime and get close to a causal estimation of the impact of the referendum.

Brexit and hate crimes

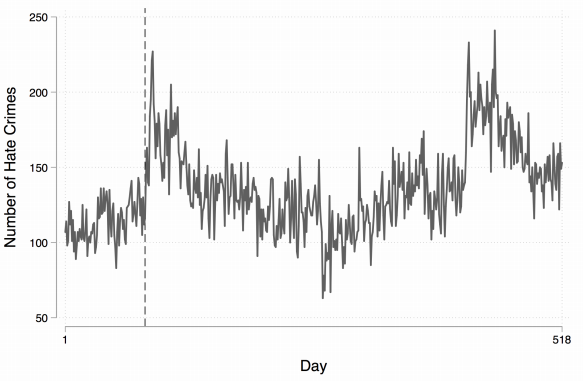

Firstly, Figures 1 and 2 show the trends of hate crime for the daily and monthly data, with the dashed vertical line showing when the referendum occurred. Figure 1 is most striking, showing the sudden increase in hate crime coming soon after the referendum and lasting for some time before declining back to (and below) pre-referendum levels. Towards the end of the graph, hate crimes increase again following a spate of terror attacks within two months of each other: Finsbury Park mosque, London Bridge, Westminster and Manchester. Again, even following this, hate crimes decline soon after.

Figure 1: Daily Hate Crime

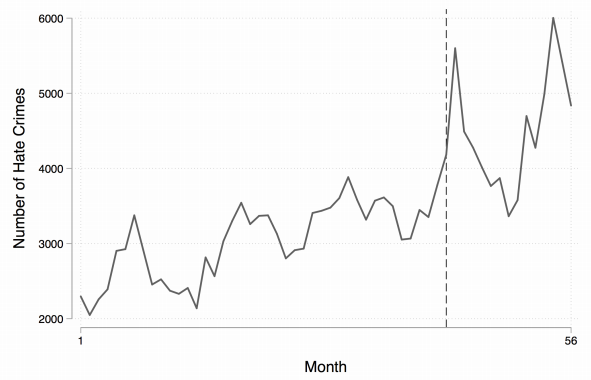

The same pattern is observed in the monthly data in Figure 2, with the referendum being followed by a large spike in attacks. Yet the graph also reveals an issue highlighted by those sceptical of the impact of the referendum: hate crimes have been on an upward trend since 2013, and always increase a lot in June and July – precisely when the referendum occurred. Is the increase in 2016, then, just another seasonal increase that had been observed before?

Figure 2: Monthly Hate Crime

To study this, I used a method called time series intervention modelling, which allows us to control for these sorts of trends as well as all other identified events in the data. I therefore controlled for all plausible events, such as the terror attacks mentioned and the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox a week before the referendum. Since the monthly data covers such a long period, I also control for the Paris and Charlie Hebdo attacks, amongst others. Finally, I also control for immigration salience using Ipsos Mori’s ‘issue index’. Even accounting for these other events, the results show that the referendum led to a statistically significant increase in hate crimes, potentially even larger than the Manchester and London terror attacks. The models show that the referendum increased hate crimes by 31 a day, or 638 in a month, depending which data is used. These estimates are remarkably robust to a large range of alternative specifications, and only loses significant if we believe the referendum can only matter in the three days following the vote.

But why? The role of the media and immigration

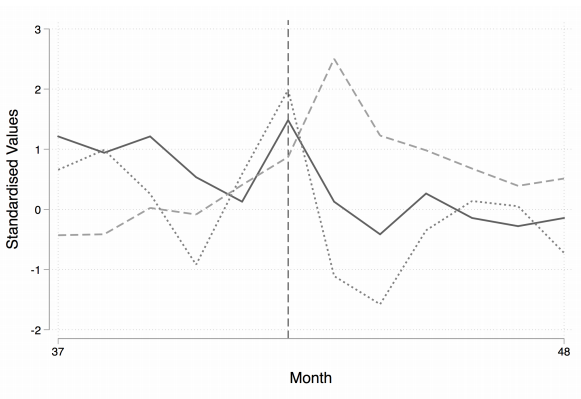

The evidence on all available data points to the referendum causing a significant increase in hate crimes. But there remains the question of why. Elections and referendums happen all the time across Europe without historically remarkable increases in race-hate crime. Whilst it isn’t possible to offer a conclusive answer to this in this post, there is a potential clue in the dynamics of public opinion, media coverage and hate crimes. Figure 3 shows the number of articles in UK national newspapers containing variations of the words “immigrants” or “migrants” (dotted line), the salience of immigration (solid line) and hate crimes (dashed line), for each month in 2016. These values are standardised to fit on the same graph.

Figure 3: Immigration Salience, Coverage and Hate Crimes

The graph has an interesting pattern. Both salience and coverage of immigration increase before the referendum (during the campaign) and peak during it. Hate crimes follow in July, peaking about a week after the referendum. All three then decline. Since we know the media has a potent effect on anti-immigrant attitudes and right-wing party support, and that events and media coverage have a large impact on hate crimes, it is not implausible that this dynamic of media coverage and immigration linked the referendum with hate crime, particularly if one considers the dominance of immigration and immigrants as an issue during the campaign. Similar evidence has also been found following Donald Trump’s election in the US. The subject merits further research. Since the data used does not include hate crimes against White British individuals (though this is still classified as a hate crime), we can be sure it isn’t a ‘backlash’ effect.

This data is from ‘reported’ hate crimes, and require no confirmation (or conviction). There is still an argument that it was awareness of hate crimes and increased reporting that led to the rise, rather than actual crimes. This cannot be ruled out. Yet, it would also mean that the same ‘increased reporting’ effect existed after terror attacks and happened in a seasonal trend. Both of these seem unlikely, given the evidence.

Conclusion

Many of the arguments against putting the blame at the referendum’s door rely on the fact that hate crimes have been increasing over the last three years, and always peak in June and July. However, even controlling for these and other events, the evidence strongly supports the conclusion that the referendum led to an increase in hate crimes – potentially even more than the terrorist attacks in Manchester and London did. But why? What was it about the referendum as an event (rather than the campaign) that led to such a powerful effect? A plausible answer lies in the negative framing and focus of immigrants during the campaign, which came to a head during the referendum.

The conclusion that the referendum led to such a large increase in hate crimes should be concerning. That the media may have played a fundamental role in linking a meaningful democratic event with prejudicial violence should be even more so.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Daniel Devine is an ESRC-funded PhD researcher at the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Southampton.

This all points, rather, to the Party-Political reinforcement of the case made for ‘Leave’ by Partys/MPs unequivocal support of the Referendum ‘result’.

It was this that signaled that xenophobia/race-hate was legitimate. This has NOT abated since.

While it would be impossible to differentiate between the announcement of the tally of responses to the referendum & the Party-Political backing for it (& so for the arguments that led to it) with regards to timing;as all of this was accomplished in the morning of June 24th 2016, a great deal of weight has to be placed upon the Party-Political signing-off on ‘a legitimacy’ for hate & all things anti-immigration. Not least because MPs/Partys retreated from their own role in assessing the responses in light of the conduct of the campaigns; as they waved ‘Brexit’ on.

In other words, reported hate crimes (and don’t forget a hate crime is as determined by the person reporting it, and this doesn’t have to be the victim, and also includes hate crimes which are based on a persons sexuality, gender, religious beliefs etc. and does not include white people who have been subjected to racial abuse) rose and fell over the last couple of years and while there is no evidence whatsoever that this had anything to do with the referendum, every tenuous link has been included to imply that asking the people of this country if they wanted to leave the EU or remain in it, gave rise to a wave of racial discrimination which was fanned by politicians and the media.

I think the point of the article was the referendum did have some impact and he showed a linkage by doing various statistical analyses and controls. He showed at least a reasonable probability of a causal link.

Still completely hung-up on the word “race.” It’s not race that people are against – it’s CULTURE. Until you realise that, all your arguments and discussions are pointless. “Race” is just a word used by the advocates of the EU/NWO to demonise those who do not want their country subsumed by Islam – a perfectly valid desire. Once more, I say “wake up.”

Since the announcement of the referendum result opponents of Brexit have sought every opportunity to declare the Leave vote as a racist one, and Brexiters as racist or “more likely” to be racist. That opponents should be so keen to label Brexiters or Leave voters as racist suggests the seriousness of the accusation of racism is today and just how unacceptable racism has become in contemporary British society. It shows how anti-racism is being used as a rather blunt weapon with which to attack Leave voters and Brexit. It is aimed at de-ligitimising Brexit without further discussion or argument, and may be even be an excuse to dismiss the democratic vote itself. It provides a convenient diversion from putting formward an argument for why Britain should remain in the EU or even how racism might be tackled. It is perhaps then not surprising that official Home Office crime records should be used so un-critically to prove a surge in racism is associated with Brexit. We might note that there is a very substantial literature that is very critical of official crime statistics, how notorious they are in terms of accuracy, reliability and lack of representativeness, how data is gathered and how a crime is defined, and to what extent a “crime report” can be considered evidence of a crime being committed. In that critical tradtion we might question how we define a “hate crime” and the context in which these hate crimes were recorded: the day after the referendum opponents of Brexit were calling on people to report and record incidences of racism. Not surprising really that we might find an increase. Perhaps more importantly it has been documented how official crime figures have been used legitimise particular political perspectives and criminalise sections of our community. These same official crime figures in the not so distant past were used by the police and right wing politicians to suggest that black people were responsible for an epidemic of muggings and other petty crimes. Thankfully there were people with sufficient critical acumen to debunk these kinds of moral panics. In the past analysts and commentators took official crime records at the very least with a large pinch of salt. In the enthusiasm to condemn a particular point of view let’s not abandone on our critical edge.

I long for the day, post Brexit, when we can all consider ourselves British and united whatever our origins. Unfortunately I am sure that low life will continue with their hate crimes whether its religion, politics, origins or just the way you look…