English local elections on 3 May take place as migrants might be finding a less divided political voice than at any time since the vote in favour of leaving the European Union. In particular, London borough elections are set to give greater voice to migrant voters than ever before, argues Joachim Wehner (LSE).

The Brexit referendum created deep uncertainty about the rights and prospects of more than three million EU citizens living in the country. Yet others were attracted by arguments that leaving the EU might bring opportunities to strengthen Britain’s ties with Commonwealth countries. The Leave campaign actively fostered this impression in the battle for votes. Priti Patel famously announced a “Save the British Curry Day” and argued that “[by] voting to leave the EU we can take back control of our immigration policies [and] save our curry houses.” Keeping out the Europeans, it seemed, would create more space for migrants from former colonies.

This was always unlikely. As Simon Hix, Eric Kaufmann and Thomas Leeper show, UK voters, including Leavers, care more about reducing non-EU than EU migration. Instead of a new openness towards Commonwealth countries, the Windrush scandal highlights their role at the very centre of the government’s efforts to reduce the number of migrants in Britain. Over the past months, the Guardian has published a string of harrowing stories of deportation, destitution and denial of critical medical treatment resulting from Theresa May’s infamous (and now rebranded) “hostile environment” policy for undocumented immigrants. The policy initially appeared to claim predominantly Black victims among long-term residents with migration backgrounds who Amber Rudd’s Home Office, in pursuit of ambitious removal targets, deemed unable to document their status. Now the scandal is spreading to non-Caribbean Commonwealth-born citizens. This shameful treatment heightens anxiety about their prospects for migrants in general.

Former Greater London Council offices, Copyright Chris Allen and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Former Greater London Council offices, Copyright Chris Allen and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

The local elections afford many migrants a formal opportunity to make their voices heard. Under Britain’s electoral rules, citizens of Commonwealth and EU countries who are resident in the UK are eligible to register to vote in certain UK elections. While EU nationals have no voting rights in parliamentary elections (and could not vote in the 2016 referendum), they do have voting rights in local elections. Nowhere in Britain does this matter more than in London. The 2011 Census counted more than three million Londoners who were born abroad, out of a total of 8.2 million. Yet surprisingly little is known about the voting behaviour in particular of EU migrants in local elections. Later this year, Elena Pupaza, a doctoral researcher at the LSE, and I will publish results from a study that sheds more light on this neglected aspect, but here is the first glimpse of an interesting pattern.

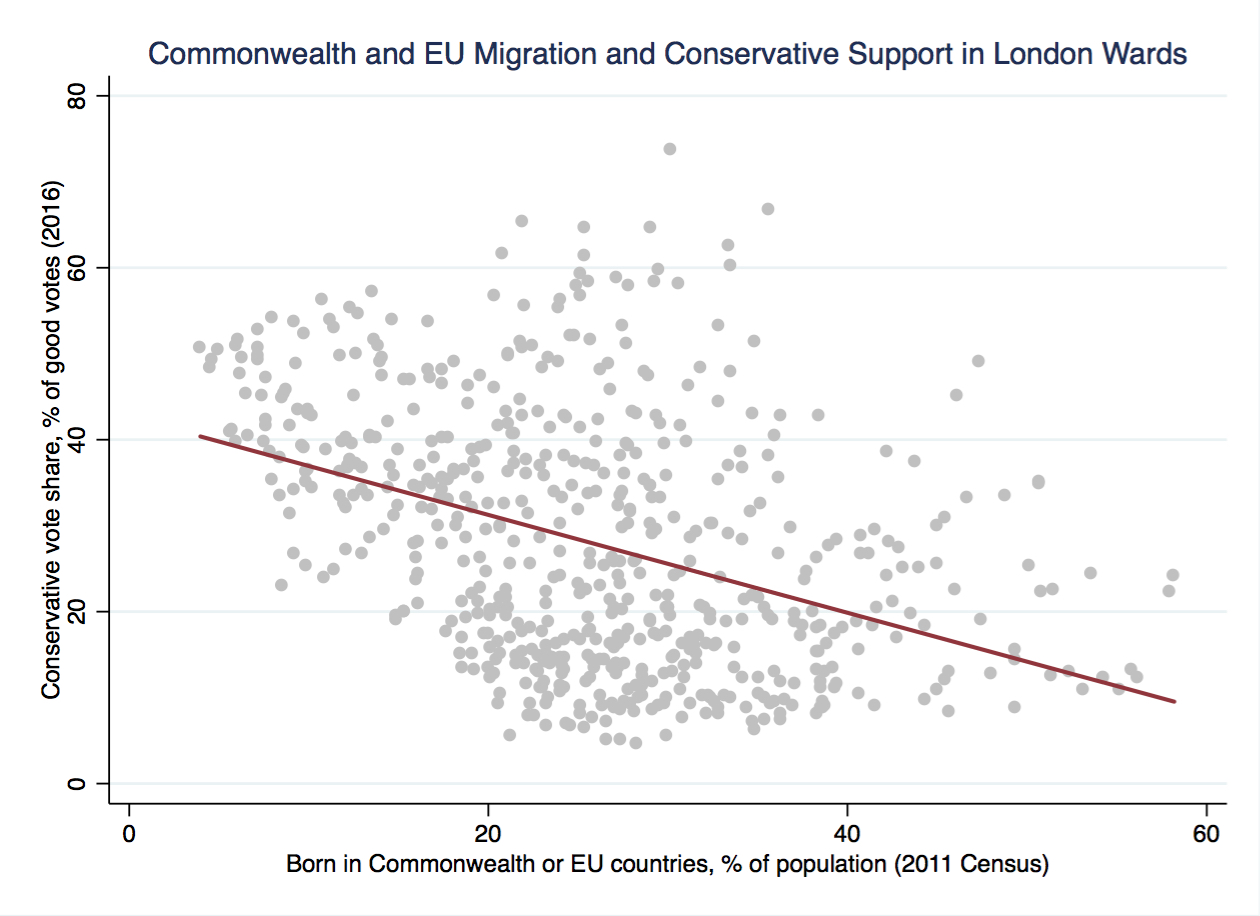

According to ward-level data from the 2011 Census, about a quarter of the population in the median London ward was born in a Commonwealth or EU country. The flagship Tory-governed boroughs of Westminster and Wandsworth have similar numbers. There is a negative relationship between the share of these migrants in the population and levels of support for the Conservative party across London. This is illustrated in the figure below that plots the relationship using ward-level data from the 2016 London election. The fitted line shows declining Tory support in a ward as the share of EU and Commonwealth migrants increases. At the same time, there is substantial variation, which suggests that voting patterns among this heterogeneous group, as well as of other voters living in a ward, are more complex than this simple perspective can reveal.

Source: Pupaza and Wehner (forthcoming) based on London ward-level data for country of birth (2011 Census, Office for National Statistics) and party vote shares (2016 London Assembly elections) from the London Datastore. The Electoral Commission provides a list of Commonwealth and EU countries whose citizens can participate in elections once they reach the voting age, which we used to calculate their ward-level share of the population.

Source: Pupaza and Wehner (forthcoming) based on London ward-level data for country of birth (2011 Census, Office for National Statistics) and party vote shares (2016 London Assembly elections) from the London Datastore. The Electoral Commission provides a list of Commonwealth and EU countries whose citizens can participate in elections once they reach the voting age, which we used to calculate their ward-level share of the population.

What this historical pattern means for Thursday’s election will partly depend on the turnout of registered migrant voters. Have they become disillusioned, or will Brexit and the Windrush scandal motivate them to cast a ballot? The Conservative party is unlikely to have gained support among migrant voters, so with significant participation, they could play a crucial role in the more contested wards and boroughs. The question then is who they will support. The Liberal Democrats, in particular, have been targeting EU voters, but historically other parties have profited more from the presence of migrant populations.

In the longer term, much depends on the voting rights of migrants going forward. Those of EU migrants in a post-Brexit Britain, which Rob Ford discusses in an insightful piece, are uncertain. Historically few EU migrants have sought to acquire British citizenship and the wider voting rights this entails, but this is rapidly changing. For some Commonwealth migrants, in particular, one challenge may come from the introduction of voter identification measures piloted in these elections. Rightly condemned by the Electoral Reform Society, ID requirements are notorious in the United States, where they have been used in deliberate attempts to manipulate elections by depressing the participation of minority voters.

For some, these local elections are predominantly about potholes, parking and fly-tipping, but others may see a first chance to use their electoral voice following the 2016 referendum. The results from London boroughs, in particular, will offer an indication of whether and how migrants might use their voting rights to engage in Brexit Britain’s politics.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It has concurrently appeared on the Euro Crisis in the Press blog.

Joachim Wehner is Associate Professor in Public Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Amongst others, his current research examines the consequences of expansions and restrictions of the right to vote.

british passport holder mandatory. like it is in France. there, they don’t let any blow ins vote, you cannot just turn up live 6 months and vote. all the voting i ever witnessed in France when i lived there (1987-2006) it was on presentation of french I.d. card or passport.

catch up uk!- better still, copy/ paste Australian migration policy. that would really solve any issues in under 2 years.

Not everyone gets a chance to travel, so many UK citizens do not have a passport. The ONS reports that 9.5 million residents of England and Wales in 2011 said they did not hold a passport. Voter impersonation is not a problem in this country, so who benefits when it gets more difficult for certain people to vote?

Labour opposes any idea of a national ID system to be used for election voting qualification. I don’t even know if there’s any other country in the world where you don’t need any form of ID to vote. This is a joke at the point!

As for the UK copying the Points System migration policy as done by Australia, fat chance of that happening when we get news leaks today about Theresa May personally vetoing requests by THREE CABINET MINISTERS to grant extra visas to non-EU doctors to work in the NHS! How much more stupid can she get?

– exactly why i saw the clusterf***k coming 6 years ago and emigrated to Australia. i live here on the gold coast, in security, and have 1st class free medical, and retire here later if i decide to work in the UK. actually i know several doctors here in Australia who had to jump through hoops to get residency. one is french, others from india, china.. my french doctor tells me he had to produce records from schooling and university plus all the police and health checks. decades of doors open to anyone has brought this situation to the UK the UK terrible migration policys, border controls and appalling law enforcement. I actually lived 19 years in paris, and I.d. is checked by police in the street on a regular basis, in pubs, building sites in fact any public area. you must show french i.d. to vote aswell (theres a novelty..). its been like that since i moved there in 1987.