Does online campaigning foster ‘echo chambers’ and exacerbate the polarisation of society? On Facebook, Leave and Remain supporters behaved very differently. Pro-Remain users commented mainly on like-minded Facebook pages. By avoiding confrontation with their political opponents, Remainers showed behaviour characteristic of an ‘echo chamber’. In contrast, Leavers spread their messages on pages spanning the ideological spectrum, and they sought to incite confrontation by frequently posting on the walls of their ideological adversaries. Michael Bossetta (University of Copenhagen), Anamaria Dutceac Segesten (Lund University) and Hans-Jörg Trenz (University of Copenhagen) chart citizens’ media and campaign cross-posting behaviour to examine patterns of political participation on Facebook.

Does online campaigning foster ‘echo chambers’ and exacerbate the polarisation of society? On Facebook, Leave and Remain supporters behaved very differently. Pro-Remain users commented mainly on like-minded Facebook pages. By avoiding confrontation with their political opponents, Remainers showed behaviour characteristic of an ‘echo chamber’. In contrast, Leavers spread their messages on pages spanning the ideological spectrum, and they sought to incite confrontation by frequently posting on the walls of their ideological adversaries. Michael Bossetta (University of Copenhagen), Anamaria Dutceac Segesten (Lund University) and Hans-Jörg Trenz (University of Copenhagen) chart citizens’ media and campaign cross-posting behaviour to examine patterns of political participation on Facebook.

The explosive Cambridge Analytica scandal is the latest instalment in the ongoing saga about social media’s impact on elections. Much of the recent hype has focused on campaigns and their use of dubiously acquired data to target voters on Facebook. The role of citizens, however, and the undercurrent of political activity that they generate in Facebook comment fields, has largely been overlooked. If we think of campaigns as the tactical leaders who devise online strategy, it is ordinary citizens who form the infantry and fight for their opinions in the trenches.

But how did this digital battle unfold during the Brexit referendum? Broadly speaking, there are two possible scenarios. The first is that citizens engage with a variety of political content across the ideological spectrum. The second scenario is that citizens would tend to read sources they already agree with, primarily engaging in discussions with the like-minded. This latter scenario would indicate so-called ‘echo chambers’, whose existence might lead to the increasing polarisation of society.

In a recent study, we sought to evaluate whether citizens’ commenting activity around the referendum indicated a cross-pollination of opinion or conversely, a trend towards political polarisation. We collected data from the Facebook pages of six British media and three political campaigns, in order to analyse the commenting patterns of citizens across both types of pages.

In traditional campaigning, politicians diffuse messages through the media. However, on Facebook politicians campaign alongside the media. In other words, media and campaigns are competing for engagement on the same digital platform. We therefore aimed to uncover whether there was any connection between citizens’ commenting across media and campaign pages. Does citizens’ engagement with political news drive them to become involved in online campaigns? Or is it the campaigns that lead people to take their political opinions into the comment fields of the news?

To answer these questions, we traced the commenting activity of Facebook accounts that left a comment to a post issued by a British media outlet (Guardian, Independent, Daily Mail, Daily Express, Telegraph, or Times) or one of three political campaigns (Stronger In, Vote Leave, or Leave.EU). Using the VoxPopuli data harvester, we collected all posts and comments from these pages over an 18 month period (June 1, 2015 – November 30, 2016). Overall, we collected nearly 34m comments from 7m unique users. (We studied users’ activity only through their anonymous user identification numbers. We did not report any personally identifiable information in the study, in order to safeguard the privacy of users.)

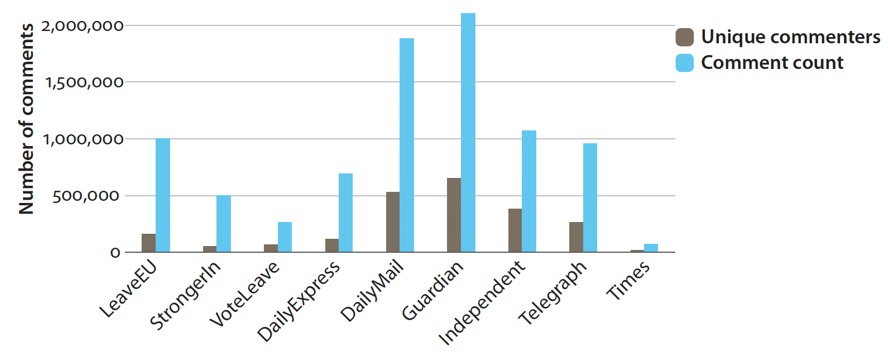

Not all of the posts we collected from the media dealt with politics. We therefore built a dictionary of political keywords to capture only political news stories from the media. We found that approximately a quarter of the British media’s Facebook posts were related to political news. After removing non-political media posts, we retained 8.5m comments from 1.9m users. Below is the overall breakdown of comments for this political dataset.

Figure 1: Commenting activity (political posts)

Figure 1 reveals three findings of our study. First, a relatively small number of users were responsible for the majority of comments. In fact, 70% of the users in our dataset left only one comment over the 18 months studied. Second, in terms of the political campaigns, Leave.EU appears to drive the most activity (although it should be noted that this campaign was active the longest). Third, political commentary on Facebook overwhelmingly took place in British media pages – not on those of political campaigns. This can be partially explained by the fact that the media pages have been around longer, and therefore have larger subscriber bases. Moreover, our political keywords included topics outside of the immediate Brexit debate, such as the rise of ISIS and the American election.

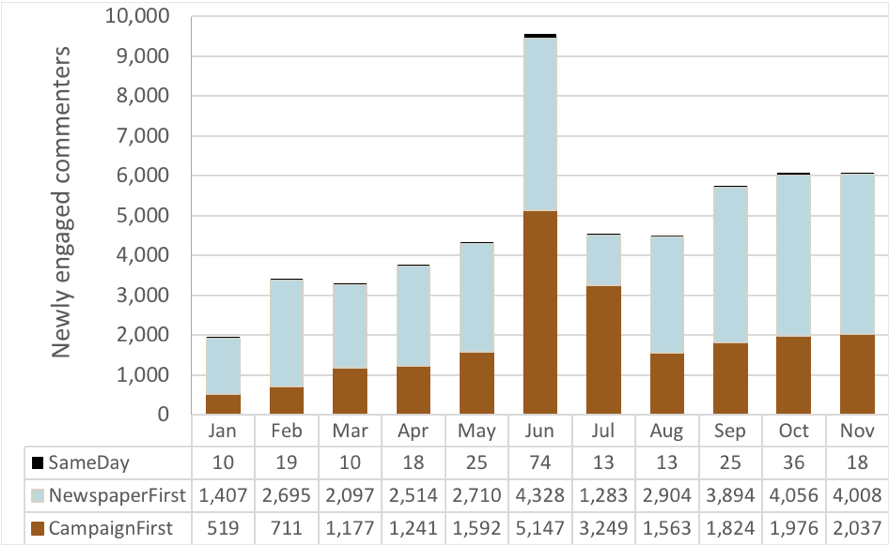

We cast a wide net of political keywords to see whether those interested in political news broadly – not just news about Brexit – were more or less active on the political campaign pages. The next figure reports what we refer to as “cross-posters”: those users who commented on both a political news story and a post from one of the campaigns. We divided cross-posters into two groups, based on whether they first commented on a media post (“Newspaper First”) or campaign post (“Campaign First”). To be counted as a cross-poster, the user could not have been present in our dataset previously and must have commented on both types of pages within the same month.

Figure 2: Cross-posters by Newspaper First and Campaign First

As mentioned above, most users left only one comment. The population of cross-posters is therefore relatively small (only 3.6% of users in our dataset). Interestingly, however, cross-posters were by far the most active in political commenting. They left an average of 13.2 comments, compared to an average of 4.5 from users who only commented on media or campaign pages. Figure 2 shows that cross-posters tend to first comment on the news, and then become engaged with political campaigns. This suggests that the media retain their agenda-setting role on Facebook, and that political interest in the news drives users to engage with campaigns.

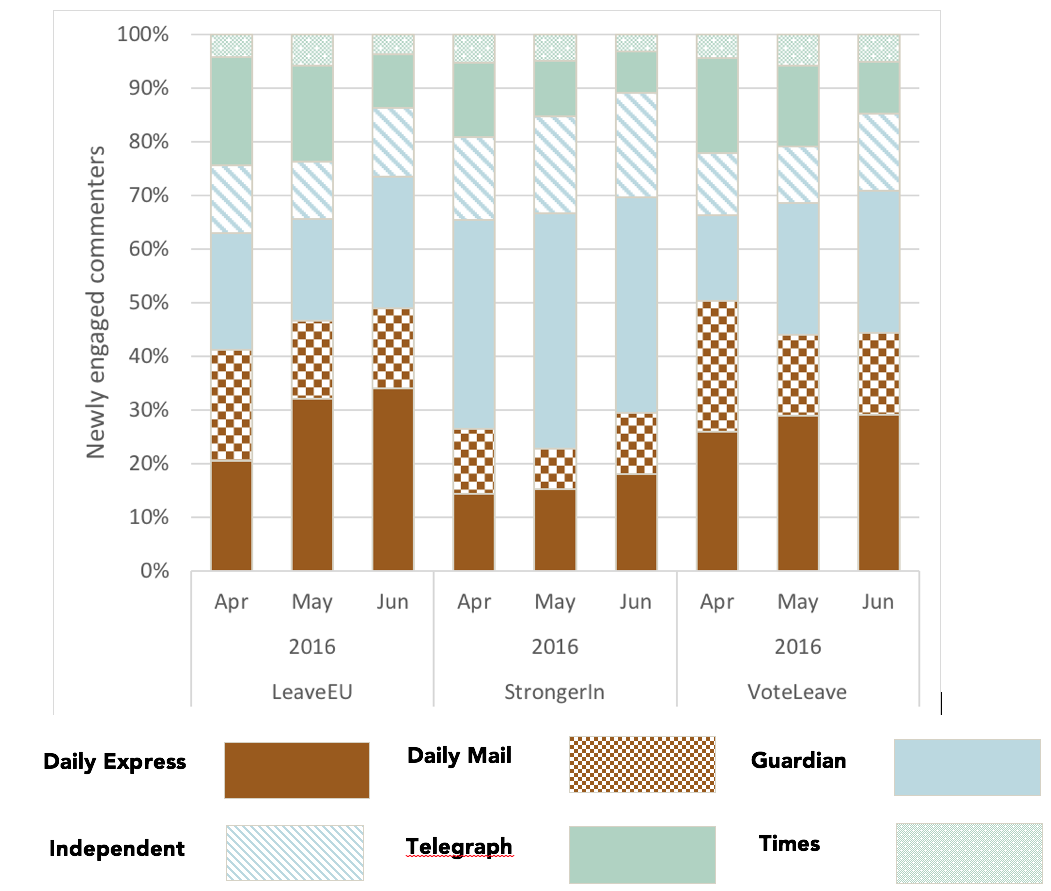

In a last step, we honed in on the “Campaign First” cross-posters to find out which media they posted to after commenting on a campaign. The aim here was to gauge whether cross-posting activity indicated high or low levels of polarisation. If users posted on media outlets ideologically similar to the campaign, this would indicate high polarisation. If users tended to engage with news outlets that held a different opinion on Brexit than the campaign they were commenting on, this would indicate low polarisation.

Figure 3: Cross-posting from campaign to newspapers

We find, as shown in Figure 3, that users who first comment to Stronger In then post to pro-Remain outlets like The Guardian and The Independent. Conversely, those who first comment on the Leave campaigns tend to post to news outlets across the ideological spectrum. This would suggest that commenters on the Remain page form an ideological echo chamber, whereas Leave commenters post across different media.

We are currently working on a follow-up study that confirms this behaviour. In that project, we divide users into Leave and Remain supporters based on whether they “Liked” or “Loved” a post by the respective campaigns. We show that Brexiteers left 80% of comments to the Stronger In page, demonstrating a high level of cross-ideological posting from Leave to Remain (but not the other way around). One potential explanation may be the “challenger effect”, according to which those against the status quo are more invested and mobilised in their campaigning style. We are also testing whether certain emotional charges are influencing these comment patterns.

In sum, the Brexit battle lines on Facebook were drawn differently depending on which side of the referendum you were on. We find divergent patterns of commenting activity, with Remain supporters exhibiting echo chamber behaviour and Leavers engaged in cross-ideological posting. It appears that the polarisation and echo chamber phenomena are more complex than previously assumed.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Michael Bossetta is a PhD student in Political Science at the University of Copenhagen and producer of the Social Media and Politics podcast.

Anamaria Dutceac Segesten is Senior Lecturer in European Studies at Lund University, Sweden.

Hans-Jörg Trenz is EURECO Professor for Modern European Studies at the University of Copenhagen.

I am 100% British, but classed as a member of an “Immigrant household” by UK Stats.

My Wife is a non-EU Naturalised British Citizen.

We Toyed with the Idea of a Leave vote, but have always been Leaning towards Remain.

About halfway through the Ref Campaign I pretty much called time on open mindedness as I was (still am) follower of many, many Brexit Supporters, on the Daily Mail and Daily Express Mailing Lists, Farage’s FB Page & Twitter.

I was not anywhere near in a polarised or Echo Chamber during the ref. I was in so many different discussions. I’d noticed a prevalence of Fake Accounts (there was a tell, which actually also pointed to “non-british origin” of the accounts) , and their main purpose was to shout down anyone who disagreed with them.

First time I knew there was trouble was when a Leave supporter said “Leaving will bring back the traditional British High Street”, and I’d asked “how would that help with Economies of Scale for nationwide chains buying in goods cheaper, and online retail giants undercutting shops when UK is almost entirely cost driven market?”.

The Abuse I got from this (allegedly 60 year old) man was breathtaking.

The whole concept of Leave was to shut out logical conversation, to threaten and shame people into silence.

I’m still on these discussions, and it’s not got any better, though they do all change tactic with alarming synchronicity.

So, in summary, Leave campaigners engaged in more trolling.

Makes perfect sense.

Kindof, though they might see it as “Were more evangelical and spread the word…”

The Leave sites were one hell of a lot more hostile than the Remain sites. They were also more likely to just “shout you down” even if you were having an intelligent conversation, there would be someone who immediately broke up that intelligent conversation posting multiple times “OUT OUT OUT!” or some similar nonsense.

It was really difficult to talk facts to people with that sort of behaviour.

> The Leave sites were one hell of a lot more hostile than the Remain sites. They were also more likely to just “shout you down” even if you were having an intelligent conversation

And the Leave voters would shout you down on Remain sites, too. Endlessly.

Yes.

I had relatively few conversations with people being polite, and the ones who were polite were either really poorly informed or putting up very weak arguments.

Notably:

The Irish guy in sunglasses from the “£350m per week” bus. He portrayed Brexit as “freedom and more choice” but every case he argued was actually less choice, which he conceded when I pointed it out to him.

Local UKiP MEP : I asked him for reasons why something was said, he forwarded a 40 page PDF which was both dubious and irrelevent.

There were a few online discussions which were clearly wrong on almost every point they argued.

Yes, all of that. And even the calm, apparently rational ones with the pile of canned arguments would, by the time you’d pointed them to sources debunking each and every one of them, just mumble ‘But… brown people’…

There has been no mention of bots in this article (unless I missed it, for which I apologise). I suppose it’s impossible to determine whether the users in your study were genuine. It would be interesting to know, and how their behaviour differed from that of genuine human users.

Hi Laura,

Yes, we did not account for bots or duplicate/fake accounts in this study. You’re right in that they are difficult to detect on Facebook (it’s a bit easier on Twitter). By looking at the most active users, we did observe some ‘inhuman’ levels of posting that would suggest bots, but I don’t think it detracts from the overall patterns of activity reported here.