What do tweets posted in the run-up to the EU referendum reveal about the motivations for the vote? Marco Bastos and Dan Mercea (City, University of London) found that nationalist and economic concerns dominated people’s concerns, but populist sentiments were less apparent. As the referendum got closer, there was an upsurge in globalist tweets.

What do tweets posted in the run-up to the EU referendum reveal about the motivations for the vote? Marco Bastos and Dan Mercea (City, University of London) found that nationalist and economic concerns dominated people’s concerns, but populist sentiments were less apparent. As the referendum got closer, there was an upsurge in globalist tweets.

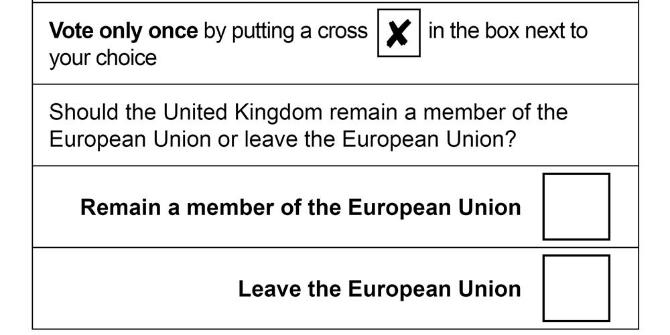

The political cleavages revealed by the referendum continue to divide the Conservative and Labour parties, exposing a major realignment in British politics. While the Scottish vote may have anticipated a shift in favour of civic nationalism, it was reportedly the Brexit vote that was driven by nativist and populist sentiments, respectively defined in opposition to internationalist and evidence-based policies.

Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris (2016) summarised the problem by way of two hypotheses: economic insecurity, or cultural backlash. The former argues that the economic decline of the blue-collar working class and a lack of access to public services such as health, education, housing, and social welfare explains the political upheaval. The latter hypothesis posits that once-predominant sectors of the population became increasingly inward-looking and averse to progressive value change, with the possibility that socio-economic hardship and resistance to cultural change may mutually reinforce each other.

We sought to test these hypotheses with a proof–of–concept study using social media signals to capture ideological shifts in British society. Geographically-rich Twitter data and machine learning algorithms were used to map the political value space of more than half a million tweets in the UK’s 650 parliamentary constituencies. We found a significant incidence of nationalist sentiments and references to economic hardship in the debate, which persisted throughout the campaign and were only offset in the last days – when a globalist upsurge brought the Twittersphere closer to a divide between nationalism and globalism.

As such, the Brexit debate on Twitter was largely motivated by nationalist and economic concerns, with three quarters of messages (74 per cent) displaying nationalist sentiments, such as the desire for the country to be self-governing, as opposed to 26 per cent that expressed globalist values, such as universal individual rights and international cooperation. Indeed, our algorithm found the conversation to be much less driven by populist and globalist issues, despite the upsurge in globalist values as the referendum approached.

Similarly, almost two-thirds of tweets (62 per cent) focused on economic issues underpinning Brexit, like trade policy, instead of expressing populist sentiments (38 per cent), such as voters taking back control from elites. In short, we found that outrage at material inequality and a nationalist upsurge helped explain the vote more than populist sentiments did. Perhaps surprisingly, tweets embracing nationalist content did not originate from economically fragile areas that were generally supportive of Brexit, like northern England, but from various other regions across the country, including remain-backing areas like Scotland.

To be sure, we did find and manually coded several thousand messages with populist sentiments. Indeed, nearly 40 per cent of tweets contained populist sentiments, but these messages were concentrated in a small number of constituencies. In only 10 per cent of the parliamentary constituencies did populist sentiments prevail, compared with economic issues, and in less than 5 per cent globalist sentiments dominated, compared with nationalist sentiments.

For example, all 72 constituencies with overwhelming support for Leave (65 per cent voting to leave, or higher) presented predominantly nationalist sentiments. Conversely, only 17 of these constituencies had a Twitter debate predominantly defined by populist sentiments, with 55 of them being classified as concerned with the economic outlook. These were regions in which Brexit was wholeheartedly embraced – and yet populist sentiments were not predominant in these regions on Twitter.

In the end, the model we built was relatively robust and accounted for nearly half of the variance found in the referendum results, but only after we combined Twitter data with demographic variables for each region that are known to be associated with Leave or Remain voters, such as the unemployment rate. If anything, the study is an indication that the social media signal does not yet offer a reliable depiction of social anxieties.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

For more information about the study, contact Ed Grover at ed.grover@city.ac.uk. The paper, Parametrizing Brexit: Mapping Twitter Political Space to Parliamentary Constituencies, was published in the journal Information, Communication & Society and is available online.

Marco Bastos (marco.bastos@city.ac.uk) is Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication at City, University of London.

Dan Mercea (dan.mercea.1@city.ac.uk) is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at City, University of London.

I find it difficult to distinguish nationalist sentiments from populist sentiments. I think the real distinction is between people whose vote was mainly influenced by feelings of economic satisfaction or dissatisfaction on one hand and those who were motivated by nationalist/populist sentiments on the other hand. In this context there is an inclination in assessments such as this one to concentrate on constituencies where a substantial majority voted leave – or indeed remain – and the conclusion that economic issues were to the fore is easily drawn. However this was a national vote and it is arguable that substantial leave votes in constituencies (mainly in the south east) were really the decisive factor in the overall result. In these cases I would assert that economic issues were certainly not to the fore. New Forest, North Devon, Bournemouth and Sevenoaks for example returned a majority for leave. While Guildford and Woking voted remain there was an identical substantial leave vote of 43.8%.