In The Language of Brexit: How Britain Talked its Way Out of the European Union, Steve Buckledee analyses and compares the linguistic features of both sides of the UK ‘Brexit’ debate, placing these discursive techniques in wider social and historical context. Combining an accessible writing style and thoughtful analyses, the book will help open up and advance the academic discussion of Brexit as a linguistic phenomenon, writes Erica Frazier.

The Language of Brexit: How Britain Talked its Way Out of the European Union. Steve Buckledee. Bloomsbury. 2018.

Steve Buckledee’s latest book, The Language of Brexit, is a detailed exploration of one of the most divisive issues of modern politics in the United Kingdom. It is an account of a fight in which one side’s desire to proceed with caution failed to inspire, while the other knew very well it was fighting an uphill battle with nothing to lose. Buckledee does an excellent job of not only analysing and comparing linguistic features from both sides of the Brexit debate, but also placing these discursive techniques in their wider social and historical contexts. Moreover, because the book was released so quickly after the UK began negotiations for leaving the European Union, Buckledee’s work can be seen as helping to open the academic discussion of Brexit as a linguistic phenomenon.

Despite the field of linguistics’ reputation for being nearly inaccessible for the lay-reader, Buckledee’s writing is straightforward, concise and even humorous at times. He does an admirable job of explaining key concepts and showing their relevance to the way the Remain and Leave campaigns communicated. In just 210 pages, readers can see detailed examples of some of the most important discursive features that shaped the debate around the UK’s future relationship with the EU.

The book includes a very extensive index and a well-structured introduction to help readers navigate the material with ease. The text is organised into two halves encompassing a series of short chapters. The first eight incorporate linguistic analyses covering key features of the debate, such as the use of ‘we’, hedging and modality, as well as the way emotionally charged words such as ‘democracy’ and ‘free’ were deployed. Buckledee also takes care to highlight inaccuracies and critique examples of discourse from both sides of the Brexit debate. The second portion of the book discusses broader subjects, such as the media’s agenda-setting role in the UK, and compares Brexit with the 1975 European Economic Community and 2014 Scottish referendums.

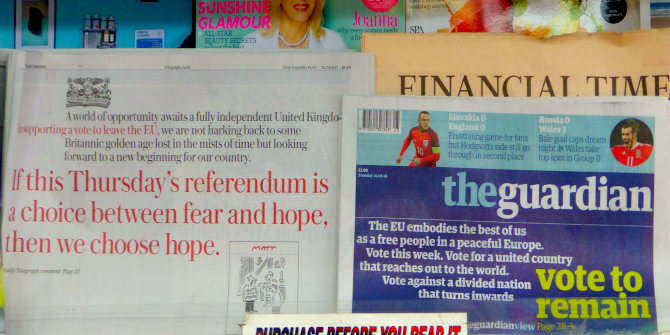

Image Credit: British newspapers, 21 June 2016 (Democracy International CC BY SA 2.0)

Image Credit: British newspapers, 21 June 2016 (Democracy International CC BY SA 2.0)

In the first half of the book, Buckledee transitions seamlessly from academic references to different, juxtaposed examples of the chapter’s linguistic theme. Chapters Three and Four are good illustrations of what makes this linguistic portion of the book such an engaging read. The former features an informative introduction to imperative structures with examples of differences between English and other languages. Although this extensive setup may feel quite remedial for those more familiar with linguistics, it is helpful for those who are learning about these concepts for the first time. This working description of imperative structures is then applied to examples of discourse taken from the Brexit debate in order to demonstrate their impact on meaning. Chapter Three also features reproductions of posters from the Leave campaign, which offer a nice visual element to Buckledee’s analyses. Chapter Four discusses the ways words such as ‘we’ and ‘they’ were used to signal belonging and/or exclusion, particularly in the discourse of the Leave campaign. These analyses are interesting in that they explore some less obvious linguistic techniques that had a significant impact on meaning by alternately building solidarity and othering. The chapter also exposes some of the sexist language used to discount the opinions of ‘outspoken’ women.

Chapter Nine is a good example of the content covered in the second half of the book. It describes broader historical events by outlining some of the parallels and differences between the Scottish and Brexit referendums. The chapter opens with concise descriptions of the main parties that pushed for the two votes respectively: namely, the Scottish National Party and UK Independence Party. It then builds a persuasive case to explain the very different outcomes in 2014 and 2016, arguing that while pushing fear of the unknown worked in the first case, it was ultimately a misguided strategy in the second.

Throughout the text Buckledee draws upon an impressive variety of sources, incorporating solid academic references as well as the expected citations of key newspapers and the official Remain and Leave campaign materials. There are also some more surprising references to message boards, social media hashtags and tongue-in-cheek parodies of the tabloid press, which add some levity and a ‘real-world feel’ to the material. Buckledee also helps readers from outside the UK access bits of slang with which they might not be familiar, such as the expression ‘The Sun wot won it once again’.

Additionally, certain portions of the book offer a very human, personal perspective. Buckledee is open regarding his personal stake in the Brexit debate as a British academic living and working in another EU member state. However, he also approaches those who voted to leave without the kind of condescension ‘Remainers’ were so often accused of displaying. Readers get the impression that this way of writing is due not only to hindsight or geographical distance from the thick of British politics, but also to the author’s compassion and desire to understand the ‘ordinary’ people he is writing about and treat them with dignity.

Because the book’s linguistic analyses are derived from a group of examples meant to highlight key features of a given discourse—all selected by the author himself—critics could argue that the text is simply an example of Buckledee’s own interpretation of events. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that another researcher would have included all of the same quotes and posters to analyse or draw out each of the linguistic features Buckledee chooses to cover. However, the text’s arguments are sound and well-supported. Rather, it seems that the book’s main shortcoming—as with so many Brexit discussions—is its very limited discussion of Northern Ireland, a jurisdiction which arguably played the role of kingmaker following the General Election of 2017, and will likely continue to raise concerns as the terms of Brexit are negotiated. However, this gap could easily be filled by subsequent work by Buckledee or other scholars.

Overall, the book’s accessible style would appeal to anyone interested in examining Brexit as a social and linguistic phenomenon. In the introduction, Buckledee outlines the study’s limitations and sets out some potential research projects for the future, including the way the media will portray the final settlement concluding Britain’s membership within the EU. Buckledee’s engaging writing and the thoughtful analyses he advances to unravel the discourse of the Brexit debate have left at least one reader looking forward to a follow-up text.

This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Brexit or the London School of Economics.

Erica Frazier recently completed a joint PhD in political science under the direction of Prof. John Barry at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland and Prof. Karin Fischer with the REMELICE laboratory at the Université d’Orléans, France.

Find this book:

Find this book: