Brexit has been very divisive for the Left in Britain. While some socialist intellectuals claim that it is a prize within reach for the Labour movement, it remains largely a neo-colonial project of a ‘Global Britain’, writes Peter J. Verovšek. He argues that the case for Lexit ignores the right-wing roots of the EU referendum, and that it will be no prize for Labour.

Brexit has been very divisive for the Left in Britain. While some socialist intellectuals claim that it is a prize within reach for the Labour movement, it remains largely a neo-colonial project of a ‘Global Britain’, writes Peter J. Verovšek. He argues that the case for Lexit ignores the right-wing roots of the EU referendum, and that it will be no prize for Labour.

Much like support for Europe, Euroscepticism cuts across the political spectrum rather than through it. The rifts within the Conservative Party – whose members have to take decisions while in government – are obvious. However, Brexit is equally divisive for the Labour Party. While some took to the streets of Liverpool outside the party’s conference calling for a ‘people’s vote’ to stop Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn has remained conspicuously silent.

In contrast to the reticence of the Labour leadership, some socialist intellectuals have claimed – and continue to claim – that ‘Brexit is a prize within reach for the British left’. The ‘left case for Brexit’ is based on the idea that it reempowers the democratic state, which these thinkers argue the left has historically been able to use to further its agenda. Noting the importance of nationalisation – which is prohibited under EU laws against state aid – as a tool of the left, the principled argument for Lexit notes that a new socialist agenda can only be achieved once the UK is free from the quasi-constitutional constraints of the EU.

While these arguments are compelling, they are also dangerous. First, the statist, nation-based character of Brexit betrays the internationalist principles that have grounded the left. Second, Lexit threatens to undermine the left’s core beliefs by bringing it into a political coalition with free market Tories, the anti-immigrant UKIP, and the Murdoch press, all of whom threaten to coopt the leftist project with their neo-colonial vision of a ‘Global Britain’.

The Left is an International Project

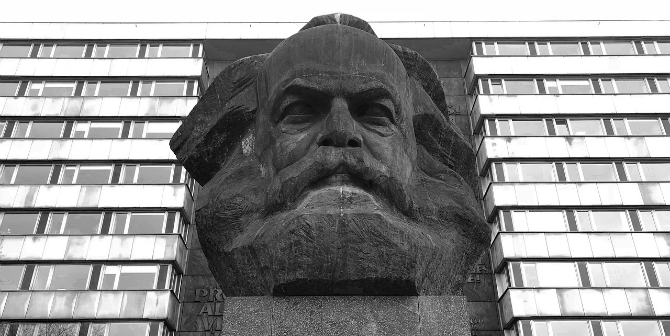

Since Marx, the left has been a self-consciously international movement that seeks to transcend both the nation and the state. As regards the former, the traditional left sees nationalism as an ideology that tricks workers into siding with local elites rather than questioning the power structures that oppress them. As a result, socialism seeks to ‘bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality’. Given Brexit’s entanglement with English nationalism and its scapegoating of foreigners, it hardly seems an appropriate vehicle for the left.

Similarly, leftists are sceptical of the institution of the state. As Marx points out, the state ‘is nothing more than the form of organization which the bourgeois necessarily adopt both for internal and external purposes, for the mutual guarantee of their property and interests’. While it does in fact do more than just serve as a committee of the bourgeoisie, the implications of the division of peoples into states is still clear: at the bottom, the institution of the state remains a mechanism for pitting individuals who should be working together for their common interests against each other.

It is true Marx believed that England – with its omnicompetent Parliament – is a place ‘where the workers can attain their goal by peaceful means’. All the British left needs to do is to take over Parliament and it can achieve its objectives through the legal process. In this sense, the Lexiteers are right that the EU’s constitutionalisation of the right to property – which prevents nationalisation through expropriation – is a fetter on socialism.

The NHS is the paradigmatic example of how the goals of socialism can be achieved through nationalisation. However, while I agree that this is a great achievement, it is unclear that the NHS sets a proper historical precedent, as it was created in an ‘exceptional rather than representative’ moment following World War II. Additionally, fact that Parliament’s omnicompetence allows for rapid and thorough transformation to occur legally also means that these changes are just as easily reversed after the next election.

Thus, although nationalisation is a powerful tool for the achievement of some of the short-term goals of socialism, Engels notes that ‘is not the solution’ since ‘state ownership does not do away with the capitalistic nature of the productive forces’. If the left is to live up to its internationalist ideals, it should be fighting the fetishism of the nation-state – an opportunity that the supranational project of European integration at least potentially offers – rather than retrenching them by supporting a statist, nationalist initiative like Brexit.

Lexit Undermines the Left

In addition to betraying the international principles of socialism, the left case for Brexit is also an example of bad political judgment. To start, it is unclear that EU regulations are the primary fetter on traditional socialism today. Many EU member-states manage to be much less neoliberal than the UK, endorsing precisely the policies – including virtually free university tuition and public control over rail and other transport infrastructure – that the Lexiteers desire and which European law does nothing to hinder.

Moreover, while the EU may frustrate some leftist initiatives, within the UK European regulations actually often serve leftist goals by protecting consumers, worker’s rights, and the environment. The situation is different in Greece, where the EU has indeed enforced brutal market liberalisation. However, England is not Greece and the EU’s effects differ depending on the national context. This explains why the majority of the UK’s left-wing parties (Labour, Green, Scottish National, Plaid Cymru, SDLP, Sinn Féin and Left Unity) and trade unions not only campaigned for Remain, but also continue to oppose Brexit.

Most importantly, the case for Lexit ignores the right-wing roots of the EU referendum. It is true that the left case for Brexit is not based on the kinds of xenophobic, intolerant, anti-migrant rhetoric that exemplifies support for Britain’s exit from the EU on the right. However, supporting the same policies as the far right means that Lexit can conceivably be coopted by these unsavoury elements.

This fear is not merely theoretical. The rapid transformation of the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) from a Euroskeptic party focused on the problems of the euro into a far movement sets a worrying precedent. In arguing for the breakup of the Eurozone, the AfD quickly attracted voters and support from the ultra-nationalist right. As a result, a movement that started out making cogent economic arguments – arguments many on the left share – soon turned into a vehicle for ethnic hatred and nationalism as its leadership of academic economist was replaced by supporters of the far right and anti-migrant protesters.

The same outcome threatens the British left if it abandons its international, cosmopolitan orientation. In trying to woo Brexit voters by promising to limit immigration to the UK the left also distracts from its actual diagnosis of the pathologies of the present. Insofar as Labour truly believes that an overreliance on market mechanisms – such as deregulation and privatisation – is to blame for the current situation, it needs to make this argument without scapegoating migrant workers in order to woo English nationalists.

Conclusion

Does this mean that the EU is a social democratic paradise? By no means. Like many on the left, I oppose European directives requiring competition in the provision of public services, court decisions that imperil international collective bargaining, as well as its suppression of Greek democracy. However, these are problems and policies that are best opposed from within the EU.

Given the global nature of contemporary problems – including rising inequality, capital flight and tax avoidance, as well as global climate change – it is irresponsible to abandon supranational European political institutions that offer some hope for politics to ‘catch up’ with global markets. Instead of counterproductively supporting Brexit, the British left should push for change within the EU where it can make a real difference at the global, systemic level.

This post represents the views of the author and neither those of the LSE Brexit blog nor of the LSE.

Dr Peter J. Verovšek is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Politics/International Relations at the Department of Politics, University of Sheffield.

Nationalisation is absolutely not prohibited by EU laws on state aid. Commercial investments are allowed providing they are done on an arms length basis and indeed I have been involved in several.

Non-commercial investments that are state aid are frequently allowed too but do need to be approved first.

Granting monopolies to nationalised companies would generally by prohibited. But that’s a very different point.

Yes and it is wrong and unimaginative to assume that Nationalisation is the only way to achieve public ownership.

There are many forms of Mutuals that exit to create social ownership.

This Marx but also Lassalle, the State is not only an instrument of the bourgeoisie, it is up to the people to change it, the ideas that predominate in the people. And this depends a lot on the work of the parties. G, DHCole is a good example The Marx of 1844 defended the individual identity against collectivization, The problem of national and European identity with respect to immigration should be treated in more depth. There is a threat to democracy

many on the ‘left’, which should be constantly up for negotiation and it’s meaning not set in stone, must recognise that the nhs and the whole ‘socialist ‘ post war project was at the expense of the brutal exploitation of the colonised world

The bottom line for me when I voted to leave is the 200mile fishing waters lost when the UK joined the EU.and the devestation it has caused in Northern seafishing towns. 12 miles is hardly enough to take a fishing line to.let alone to sustain a community. The second was my gut fury about the attitude London has to the rest of us. The 2008 crash disgusted me. I would like nothing better than to see London’s wings clipped , as very little of the City’s behaviour has changed.since then as far as I can see.London hides behind the screen of being a World City. which somehow evokes a liberal generous aura.when in fact it is more greedy immoral. than it ever was.in the past.Gina Millar,, for instance, a financial investment advisor, so beatified by London Remainers comes from Guyana,the country whereI grew up,and went to school. Guyana is now much poorer than it was when it was a colony, Even it’s sugar price is undercut by cheaper beet from the EU.All educated people seem to have left Guyana for Germany ,Canada and the UK. The small coastal towns,including the capital are quite likely to be lost to the sea as Guyana is below sea level.Guyana is mostly untouched rain forest as big as the Uk yet the country has being ignored even though it is trying to avoid logging and oil extraction. I think there is a great hypocracy when Bookers, the Guyana sugar traders are still so villified considering that the UK depends on cheap imports from Third World countries produced by people who are working for next to nothing..I would like to know what the EU is doing about that injustice. The EU was a great idea once, when the Uk was on it’s uppers in the 70s and still struggling after the second world war, but now it run by a bunch by bullies. not much different from the tyrants of recent hystory so beloved by the LSEI am beginning to think that a hard Brexit will be ok

To conflate London and “The City of London” is rather lazy. I live in Lambeth in the area around Brixton and Camberwell, our daily socio-economic reality couldn’t be further from the reality on Canary Wharf or Bishopsgate. But my area, like so many around us in Southwark, Lewisham, etc, voted overwhelmingly to Remain in the EU … only to subsequently be tossed into the same bin as ‘city traders’. When Thatcher died people were celebrating on the streets of Brixton because they had not forgotten … many Leave constituencies who were equally hard hit by the policies of the Tory 80’s and 90’s instead lent their vote to a nationalist far-right project.

Yes I agree that EU agricultural policies have hurt farmers outside of the EU. Partially this is because the EU also has farmers to protect, partially this is because it has made selfish agricultural policies. Don’t believe for one minute that by signing up along with fascists to a break from the EU you will get a chance to do anything about those injustices. Instead you will just multiply them. I am amazed how naïve Lexitters are.

Eurozone needs to be dismantled. I’d rather see France, Italy, Spain get out of the common currency than Britain rip up agreements and have nothing to replace them with.

The detriment to the argument is we have a process with a name called ‘BREXIT’ which is a place holder for group of legislation which dictates how the UK interacts in a plethora of ways with its neighbours in Europe.

Brexit could entail nothing more than repealing the 1972 european communities act. Or it can be any variation between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ forms.

Underlying problem is that you’ve have (non brit speaking) a plethora of different flavours of Thatcher over the last 30 years, thats more destructive than even a ‘hard’ brexit. Uk has already fallen off the cliff and now the debate about damage is how much damage adding an extra 10 meters to the drop will be when we’re dealing with an velocity squared formula.

Although i agree with the majority of whats been said, linked stuff like this:

“Does this mean that the EU is a social democratic paradise? By no means.” Is an understatement.

“British left should push for change within the EU where it can make a real difference at the global, systemic level.” Unfortunately we’ve had 10 years of Europhile strategy to somehow pressure the European Commission to get on with it, achieved zero so far.

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=37653