Despite protestations to the contrary, it’s clear that the process of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU has not been going to plan. It’s time we discussed ‘How (not) to talk about Brexit.’ Tim Oliver (University of Loughborough) suggests seven rules.

Despite protestations to the contrary, it’s clear that the process of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU has not been going to plan. It’s time we discussed ‘How (not) to talk about Brexit.’ Tim Oliver (University of Loughborough) suggests seven rules.

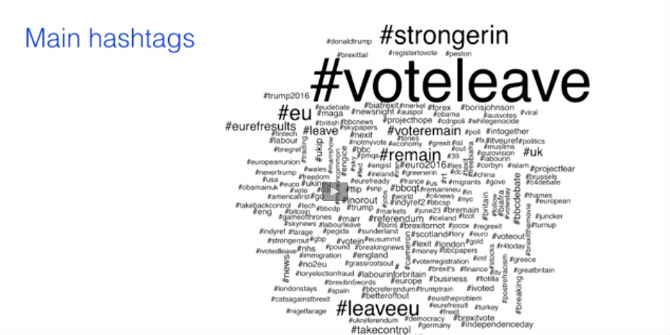

Britain’s vote to leave the EU has led to a flood of books, articles, blog posts, and more than enough tweets. I know because I’ve added my own share. It includes my new textbook, Understanding Brexit: A Concise Introduction. Concise is 75,000 words, and whether anyone can fully understand Brexit is a moot point. Brexit is the dominant issue in UK politics because so much is at stake. But are we – academics, writers, Leavers, Remainers, journalists, politicians, officials, businesspeople – talking and writing about it in ways that make sense? I’m reminded of how before the EU referendum there was discussion of, to borrow from the report from British Future, ‘How (not) to talk about Europe.’ It’s time we discussed ‘How (not) to talk about Brexit.’ As a start, I would like to suggest seven rules.

Rule 1: Be more specific about what it is you’re referring to when you say ‘Brexit’.

Academics love to define things, except, it seems, when it comes to large all-encompassing terms, which is what ‘Brexit’ has become. It’s increasingly as useless as ‘globalisation,’ ‘neoliberalism,’ or ‘Europeanisation.’ Brexit can be used to summarise a series of political processes unfolding at various levels and timeframes, but we would benefit from examining and naming them more specifically. Failure to do so risks turning ‘Brexit’ into a shorthand for most of British politics.

Rule 2: Don’t let talking about Brexit drown out the rest of British politics.

Given how much it touches on, studying Brexit can be the best way to understand the contemporary UK. To a point, that is. Brexit is not British politics, only a part of it. It has, however, taken up so much of the bandwidth of British politics that one would be forgiven for thinking that it is British politics. That does a disservice to the many challenges and debates facing the UK that are largely independent of Brexit and always have been. Of course, Brexit will have an effect on so much of life in the UK, but the UK already has the powers to change such absurdities as an unelected House of Lords, the UK’s stark and growing levels of inequality, poor infrastructure spending, or the need for sustainable military capabilities. Obsessing about Brexit can be a distraction from these and other issues.

Rule 3: You cannot be neutral. Whatever you say will be part of the fight to define the narrative of Brexit.

The fight to define the narrative of Brexit, i.e. what it was the British people meant when 52% of them who voted did so for Leave, has, whether you like it or not, been the central struggle of British politics since the referendum. Onto it have been hooked a whole host of issues ranging from choices about the UK’s political economy through to the UK’s standing in the world. This fight won’t end soon. Not only because withdrawing from the EU is not a short-term process, but because Brexit is about what sort of country the UK wants to be. This doesn’t mean everything you say has to be driven by politics. There exists a wealth of data, information and analysis which goes beyond the partisan bickering found in most outlets where the focus can be on the internal bickering of the Conservative and Labour parties. Whether it’s the plethora of EU reports on Brexit or UK parliamentary reports (never overlook the evidence sections), a lot of issues have been covered by high quality analysis that can, if we use it, create a better informed and high-quality fight.

Rule 4: Don’t assume the British people or elite understand the UK state and politics.

In the early stages of drafting Understanding Brexit my publisher warned me not to take for granted a general reader’s knowledge of the topic. I sympathised from having taught political science for over a decade. Knowing how few people understand the EU, I included a section on the EU’s evolution, institutions and key policies. In doing so I overlooked that a lot of people in Britain, including all the way up to Ministers of the Crown, have rarely thought about or been taught about the UK state, its evolution and how it operates. If Brexit is about what type of country Britain wants to be, then that in part stems from varying levels of knowledge and satisfaction at its current setup. I’ve often found that explaining Brexit involves helping fellow Britons understand our country.

Rule 5: Recognise that the British (and you) are on a steep learning curve about the UK, the EU, and the wider modern world (especially trade).

It follows from Rule 5 that when talking about Brexit you need to take into account that many in Britain are being presented with a series of questions and debates about the country’s identity, society, political economy, trade, security, international position, constitution, legal system, sovereignty, unity, party politics and the attitudes and values that define it. Those debates long predate the vote, but the referendum and result not only brought them together but poured fresh fuel into each. And this is before we turn to the need to learn about such matters as free trade deals, tariffs, non-tariff barriers, regulatory convergence, WTO schedules and so forth. Whether it’s the British public, ministers, officials, journalists or experts, we have all been put on a steep learning curve. The process involves lots of uncomfortable questions and silences for everyone including you.

Rule 6: Remember that Brexit can bore people. A lot.

It might have come to dominate British politics, but that does not mean Brexit excites people. Pollsters have long pointed out that the issue of Europe has rarely excited the British people. The topic only excites when it connects to issues that people do care about: immigration, the economy, housing, English identity, Scottish independence, or the NHS. For those ‘Brexhausted’ there is no sign of a let-up. The outpouring of books, articles, chapters, reports, media articles, TV programmes, conferences, assemblies, workshops, speeches, art work, plays, even poems, looks set to continue. In part this is because so much remains to be explored and discussed, not least some big questions about the UK itself. Hopes the referendum would be cathartic, settle Britain’s ‘European question’, or be a great exercise in democratic debate have been dashed by a debate and result that has instead added to existing divisions, created more questions than answers, and left Britain with a debate that often distracts from the day to day needs of the country.

Protester at an Anti-Brexit rally in Liverpool, September 2018. © Tim Jokl / Flickr

Rule 7: Don’t patronise, belittle or ignore the British people.

All sides have been doing this, including Leave. Too often I have heard Remain supporters belittle the British people for the choice made with a slim majority. That result has left some on the Remain side too willing to apologise for Britain and dismiss it as a country doomed to oblivion. It has added to a certain sense of decline and guilt about Britain’s past that has long overhung and hamstrung British pro-Europeanism. Commentators elsewhere in the EU have not helped. The UK is not the aberration some elsewhere in the EU want it to be. British Leave voters are not all peculiar, racist hangovers of Britain’s imperial past. They can and do, to a certain extent, mirror feelings found across Europe. The vote was a vivid reminder that nation states and nationalism still matter. Leave campaigners and those who have rushed to study Leave have also failed, and sometimes failed miserably to not patronise the British people.

Despite protestations to the contrary, it’s clear to all but the most ardent Leave voters that the process of withdrawal has not been going to any Leave plan because, of course, there was no plan. The rush to celebrate, sympathise with, or study the 52% who voted Leave has meant largely ignoring or taking for granted the voice and concerns of the 48% who voted Remain. That explains why Theresa May, Leave campaigners and many analysts blinded by a one-sided focus on Leave voters were shocked when in the 2017 General Election it was the votes of angry Remain voters that played a crucial part in unexpectedly depriving the Conservatives of their parliamentary majority.

This article gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Brexit or the London School of Economics. This article also appeared on the Clingendael blog.

Dr Tim Oliver is Senior Lecturer at the Institute for Diplomacy and International Governance at Loughborough University London.

For it to be true that: ‘Britain voted to leave the EU’ two other things must first be true.

– That ‘rule of law’ & Democracy are mere niceties.

– The electorate rightly respond to being patronized.

For, the sole reason the responses to the 2016 referendum led directly to ‘Brexit’ is because Conservative Party policy took on the aspect of ‘Holy Writ’.

And – what can be more patronizing than telling the electorate that their vote is in the gift of a (here today & gone tomorrow) Politician AND what they actually opted to ‘vote’ for is to be decided ONLY after the fact?

I think this article is very thoughtfu but perhaps you have left out an 8th reason peop;le are thinking about the EU.The main anger comes from areas outside London who have been left behind. This is a patronising term because what has happened in the case of Fishing is tht the Uk has lost it’s waters to EU rules..10 years ago i was shocked to hear from one of the so called governing elite that all the Uk needed was the City financial service sector. The money from there would then trickle down by government handouts , untill of course the 2008 crash. The job of Government is to protect its country from poor restrictive laws, including EU laws which have prevented people from working.. You can hardly say that Fishing belongs to a past industry when there is such a huge demand for fish.The Uk government s have sold us to the EU elite who are continuing to patronise the Uk and treat us badly when we as a country are paying through the nose to be in their club.David Cammeron tried to do something about the bombastic unelectied EU officials and their unbending minds but failed.

The real problem with Brexit, however you define it, is that only a handful of people in the UK know what the true consequences of any form of Brexit are, and nobody listens to them.

I do not count myself in that number, but I have listened to or read options from a few of these people. And it’s not pretty, and nothing like the spurious claptrap that is mostly talked about Brexti including on this website.

One thing for sure, the only kind of Brexit that will not be a disaster, sort term and long term is membership of the EEA and Efta with a customs union, at least temporarily. There would be economic, political and social problems with this option, but it would be manageable, just. Leaving the customs union and single market will decimate our manufacturing in this country, a Free Trade Agreement or not. No deal would plunge us into a recession and perhaps drag the finely balanced world financial situation down with it.

How any government masquerading as a democratic government could even be contemplating initiating such a disaster beggars belief. Even pulling the chestnuts out of the fire at this late date will see us suffer a lot and would be totally our own doing. The hubris of our minority government is truly staggering.

The author makes a point of saying we shouldn’t patronise people or bore them. Is it patronising or boring to discuss the greatest existential crisis to the UK since the Second World War? I think not.

EEA + EFTA + CU. So EFTA does trade deals with other countries around the world. CU the EU dies trade deals around the world. So which trade deal does the UK use or perhaps both.

There is a reason that the EEA + EFTA countries at the moment are not in the customs union or a customs union. But perhaps we can cherry pick.

EFTA countries can choose how to approach international trade, there is no EFTA mandate.

The current EFTA countries have never been in the EU and chose to carry on with their own international trade deals. The UK has been a member the EU for over 4 decades and international trade has been through the EU. It makes sense to carry on with that at least temporarily as there will be so many other things that need sorting out too. And, of course, the Irish Border problem really needs the UK to remain in a customs union with the EU too.

“Despite protestations to the contrary, it’s clear to all but the most ardent Leave voters that the process of withdrawal has not been going to any Leave plan”

Yes, the plan was that we all voted and we all then pulled together to best implement whatever the majority decided. Leave naively thought that was what would happen, but they were wrong. So Macron, for one makes it clear that the EU should not give concessions to the UK because that would reduce the chance that the UK holds a second referendum. The Remainers outside and inside Parliament are undermining the negotiations and thereby undermining our democratic decision.

The Remainers Plan is also wrong. They think they can reverse Brexit and the Leavers will say “OK, fair fight, thanks for pointing out we were wrong”. That is not what will happen in so many ways. The recent march in London would look trivial compared to what would happen if Brexit were reversed. Furthermore, I fear that if Brexit is reversed, then a very small minority will do their best to ensure all EU immigrants will feel unwelcome in this country however long they have been here. The exodus of EU nationals would almost certainly increase if Brexit were reversed.

Despite what may a turning back to austerity / frugality for another couple of tears leaving on WTO rules will enable the UK to sort it self out.

No EU interruption on obeying their rules except on appreciation of their standards when it suits us.

No hard border unless the EU requires one on their side.( We would have kept our bargain with the DUP.) and they can then argue the toss with Eire and reach an agreement or not. Do we need an agreement from the EU to Leave the EU

The UK would have its freedom? I am a Brexiteer but want an almost independent UK. Something the EUwill not offer,

Further arguments,disagreement and whispering will not help. Time for a consensus to Leave from our MPs. At least from those that want some or all of the above.