The EU has not given the UK what it wanted – which was free access to the Single Market without freedom of movement and the constraints of European Court of Justice rulings. This is because the EU fears that giving into the populist Euroscepticism Brexit represents would trigger a wave of further departures. Horatio Mortimer (LSE) reports on the latest Continental Breakfast seminar, which was held in Madrid on 6 November 2018 under Chatham House rules.

The EU has not given the UK what it wanted – which was free access to the Single Market without freedom of movement and the constraints of European Court of Justice rulings. This is because the EU fears that giving into the populist Euroscepticism Brexit represents would trigger a wave of further departures. Horatio Mortimer (LSE) reports on the latest Continental Breakfast seminar, which was held in Madrid on 6 November 2018 under Chatham House rules.

A wave of nationalist populism is sweeping across the western democracies, threatening not only the prospects for European integration, but also economic and political stability right across the continent. ‘Populist’ is a disputed term, but here and in general, it is used to describe anti-system parties that claim to represent ‘the people’ against an elite establishment that is deaf to their concerns.

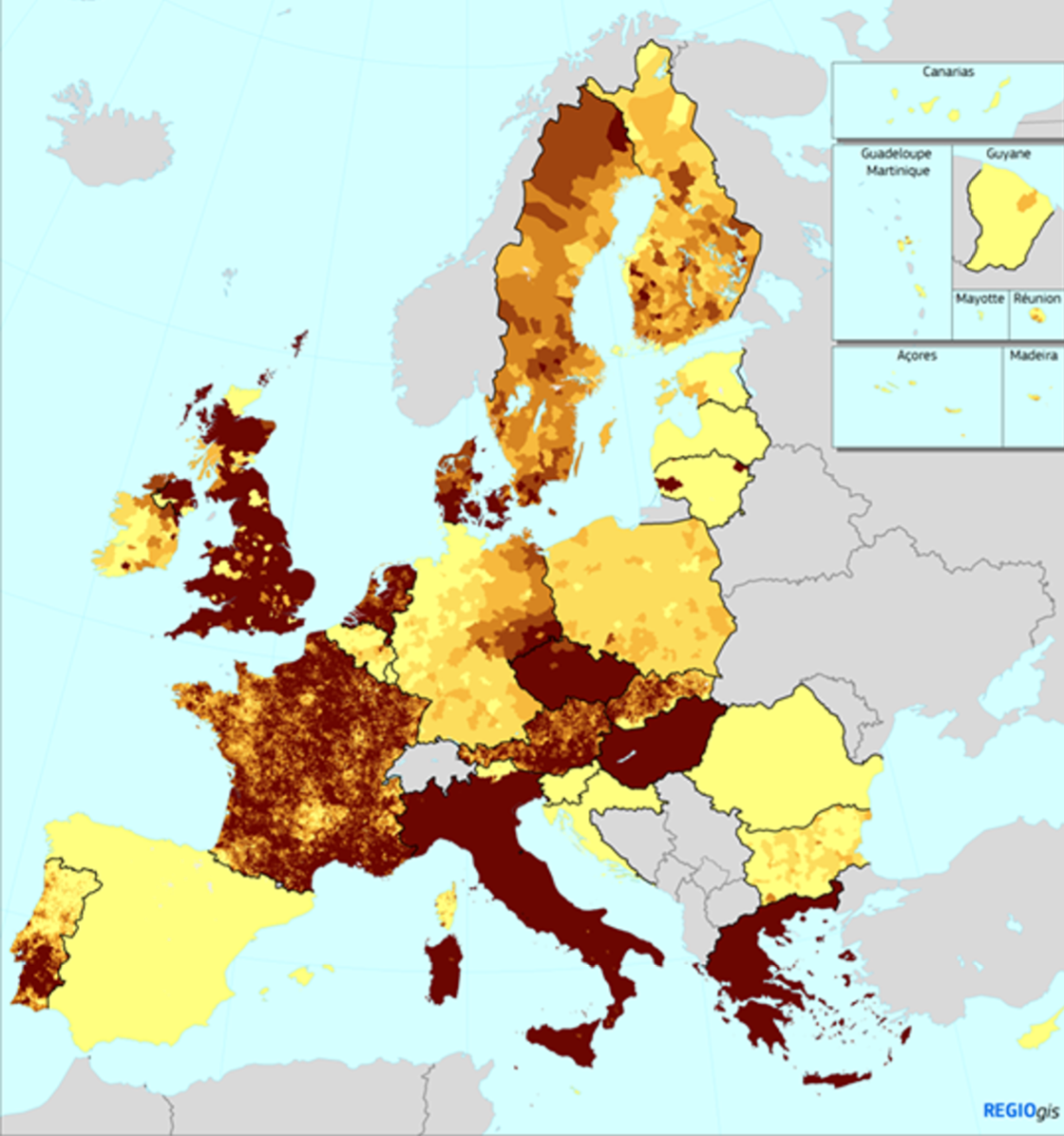

Source: Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose (2018)

The EU and the project of integration is an easy target for populist parties – so much so that Euroscepticism can be used as a variable to measure populism across Europe: the more populist a party, the more anti-EU. These parties represent close to 30% of the vote in Denmark, Austria and France. If parties only somewhat opposed to European integration are counted, then they represent 50% of the vote in Italy, Greece and the UK, and even higher in Hungary.

Source: Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose (2018)

The consensus theory is that the support for these parties comes from globalisation’s losers, people without the skills and education to compete in a global economy, who are undercut or outperformed by imports or immigrants. Older people in particular have been thought to be less adaptable to economic and cultural change, and more reactionary.

Other factors that are also sometimes associated with populist support are unemployment, inequality and lack of geographical mobility.

Rural areas, medium sized towns and small cities have suffered from rising unemployment, relative declining incomes, and are caught in a ‘middle income trap’, where they lack the skill clusters to compete with the high-value added economic regions, and yet are not cheap enough to compete with low-cost industrial regions.

Immigration is often identified as a major driver of the ‘geography of discontent’, and a catalyst of populist politics.

However, new research analyses these various factors, and points to an economic-geographical explanation for populism. The key is found in the so-called ‘places that don’t matter’. It is the formerly prosperous places that have experienced protracted economic decline, brain drain, and a sense that all opportunity is elsewhere. Once long-term decline is taken into account, low income is not a factor. Poorer regions that have not experienced industrial and economic decline show a much lower increase in the populist voting share. In regions with similar levels of economic decline, the richer ones are more populist.

Ageing is also a surprisingly weak factor. Declining areas have older populations, but once that is taken into account, older people are not more likely to vote for populists. Immigration into a constituency seems to slightly increase the vote for very extreme parties, but leads to a small decrease in the total populist anti-European integration vote. The research also finds a very weak link between the distances from national capitals to votes against European integration. Level of education is however confirmed as a strong predictor, with the less educated much more likely to vote for populists.

For the European Union, the long-term solution is to create development policies that create real opportunity in these forgotten places – in other words, something better than the palliative care of transfer payments and low-skill public sector jobs.

In the short term, however, one thing that would not be helpful is to allow the UK to free-ride on the single market, because there is a real danger that that could further invigorate populist movements that would threaten European disintegration and leave Europe with no single market to ride on, free or otherwise.

European governments and the European institutions are keenly aware of the threat from populists, and therefore will make the integrity of the single market their priority, sending a strong message that to leave the EU is to lose access to the single market. For that reason, they will be very unwilling to compromise in the Brexit negotiations.

Reference

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H. and Rodríguez-Pose (2018). The Geography of EU discontent. Forthcoming.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

If Populism prevents the loss of country status,innability to control country borders,immigration,and own welfare it will go a long way to remove the EU having such great power over people. I support this

The terminology is all quite bizarre – defining populist here as “anti-system”, when the “system” in question is presumably the EU, leading to the circular attribute that “the more populist a party, the more anti-EU”.

I think this paragraph encapsulates the myopic flaws, though: “In the short term, however, one thing that would not be helpful is to allow the UK to free-ride on the single market, because there is a real danger that that could further invigorate populist movements that would threaten European disintegration and leave Europe with no single market to ride on, free or otherwise.”

Again, a circular logic error: by conflating the EU and the single market, allowing the UK to separate the two (keeping the desirable single market aspect while ditching the unwanted spending and other EU baggage) appears “bad”, because the threat to the EU’s present power structure gets confused with a threat to the market too. Separate the two, of course, and the remaining EU baggage is expendable – a potent threat to Mr Juncker and co, but not necessarily any problem at all for the member states and the public, the bits that should actually matter. (Key aspect often overlooked in rhetoric here: a “threat to the EU” must be distinguished from a threat to the actual populace, a point the vested interests are desperate to obfuscate.)

It’s possible that single market access accelerates the decline felt by post-industrial regions since it pulls economic activity towards the centre of the market. Freezing out the UK might actually embolden regional populists rather than frightening them into submission.

I do not like the word Populism as it has become another term used to insult people who have dared stand for themselves. The EU idea was once a great thing ,but now it seems to have become too clumsy. We can all dream of Utopia. Unless the impacts of EU bad policy, which has destroyed people’s lives,,is dealt with, that Utopia will become a Hell.The comments in this essay are almost as bad as the comments which blaming the poor for being poor. It should be the job of the EU to protect such people..Our Prime Minister is trying to steer an impossible course through block headed minds. I think is says a great deal for our democracy, that there is so much passionate discussion.in Parliament. We have to remember that the people who hold EU power are unelected..We are not a poor helpless country like Greece who had money given to them by the EU without realising the it had to be paid back. The people there have said that they had no benifit fromthe money so why should they pay it back. EU money is supposed to have helped poor communities in the UK. I know of one case where the money was used to concrete over a lovely Italianate sunken garden so that the cash strapped council did not have to pay the garderners. Mrs May has bent over backwards to get on with the EU, but now I think it’s time to say no to them. I still think the EU needs the UK more than we need them. We are paying the piper and so should be abole to call the tune