Northern Ireland has played a starring role in the unfolding of Brexit, writes Lisa Claire Whitten (Queen’s University Belfast). The “particular circumstances” presented by the “unique…challenges” of Northern Ireland did not feature prominently in the early stages of Brexit but these have since defined the process.

Northern Ireland has played a starring role in the unfolding of Brexit, writes Lisa Claire Whitten (Queen’s University Belfast). The “particular circumstances” presented by the “unique…challenges” of Northern Ireland did not feature prominently in the early stages of Brexit but these have since defined the process.

The question of how to ‘solve’ the problem of the Irish border was the most contentious issue in UK-EU withdrawal negotiations and the ‘backstop’ provision designed to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland has been the stumbling block on which the domestic ratification of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement has tripped again, and again, and again.

Many words have been spent analysing the intricacies of Northern Ireland facing Brexit but less has been said about the historical significance of the very fact that this is so. Northern Ireland’s place as the fulcrum on which much of the Brexit process has so far hinged breaks a well-established, little acknowledged, norm in UK political and constitutional history whereby Northern Ireland has been a place on the margins, a problematic exception, the site of considerable constitutional experimentation but always on the sidelines of history. That is, until Brexit.

A problem of accession

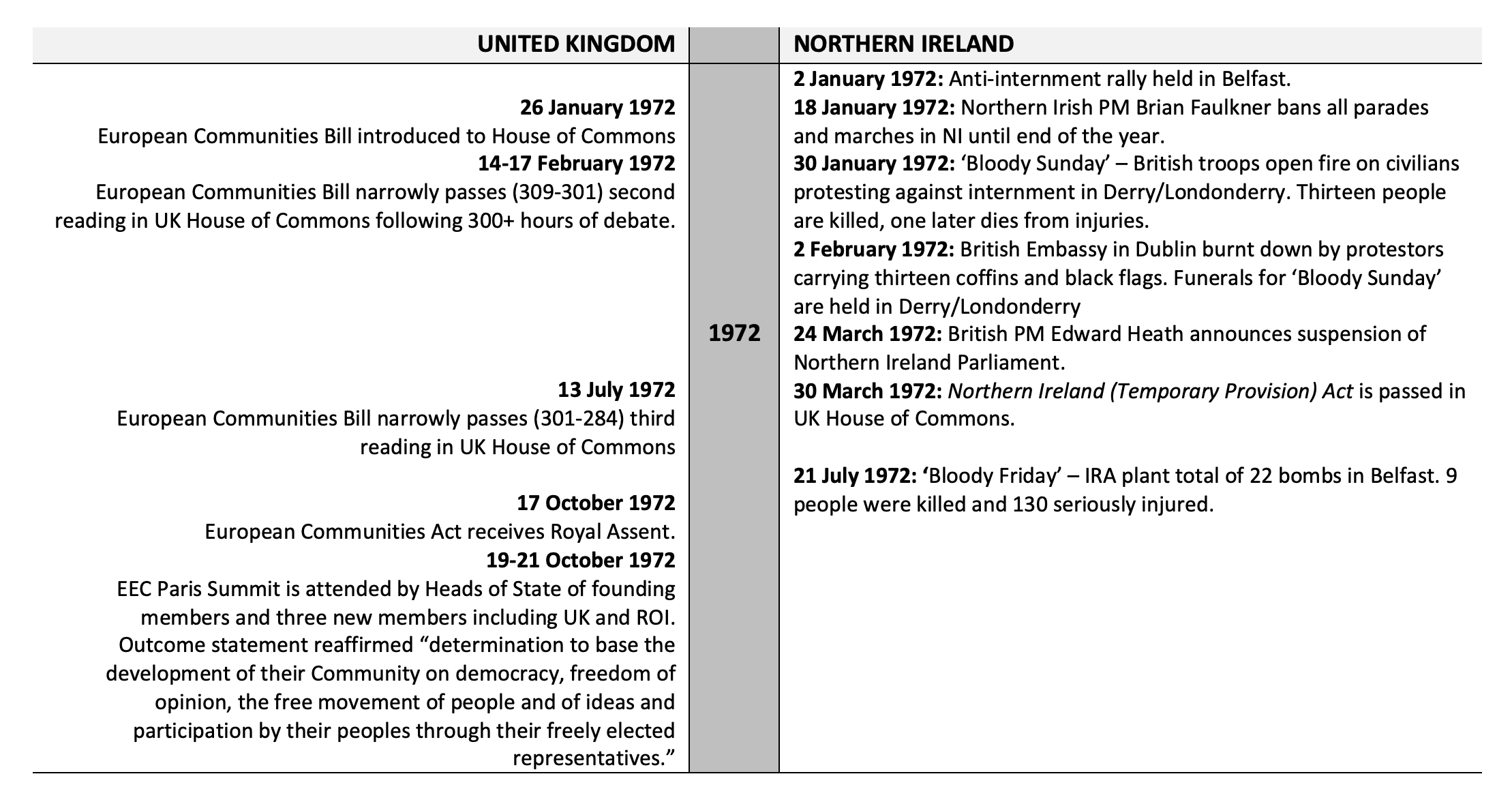

At the time of the UK’s accession to the EU, the security situation in Northern Ireland was severe. As the European Communities Act 1972, which gave legal effect to the Treaty of Accession of Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom 1972, progressed through Westminster the people of Northern Ireland endured one of the worst years of violence and political turmoil of the conflict known as The Troubles.

Originating in a series of civil rights marches the conflict in Northern Ireland came to be understood as an ethno-nationalist dispute between two communities with opposing visions for the constitutional future of the place: Unionists’ preference to remain in the UK and Nationalists’ preference for Irish unification. Yet, despite the seeming relevance of the Northern Irish situation to both the UK and the Republic of Ireland, records of the accession negotiations indicate that the situation was treated as a domestic UK issue, unmentioned in the course of the countries’ simultaneous process of joining the EEC.

Among British politicians, at the time Northern Ireland was considered a particularly troubling problem but one with little or no bearing on the broader political and constitutional shifts involved in joining the EEC. At the European Communities Bill second reading the situation in Northern Ireland was referenced just once as a means of admonishing misplaced parliamentary pride. In the eerily apt words of Liberal MP for North Cornwall:

“…[we] sometimes claim to have a political genius – although the events in Northern Ireland…have made one wonder” [c.717].

During the European Communities Bill’s third reading, again, Northern Ireland was mentioned once by Labour MP for Manchester Central who used it as an off-hand derisory example:

“So much for the so-called impossible economic burden which will be put upon us [by EEC membership] and which it has been said will reduce us to the status of Northern Ireland” [c. 1896].

In the same year speaking at the Conservative Party conference then Prime Minister Edward Heath described Northern Ireland as the “most terrible problem” the country faced, one that “haunts us every day”. In emblematic language Mr Heath went on to implicitly exclude Northern Ireland from the “staggering” historic achievements of the British people made all the more remarkable due to their position as “an offshore island of a few million people”. The singularity of the island vision conjured by the Prime Minister sticks in the ears of those living on the other side of the Irish Sea. Alongside the sequence of events during the UK’s accession the political language of the day is reflective of a well-established but little acknowledged convention whereby Northern Ireland has been characterized as a problematic exception; simultaneously placed apart and placed within. In the early stages of Brexit there was a distinct sense of déjà vu…

The echoes of history

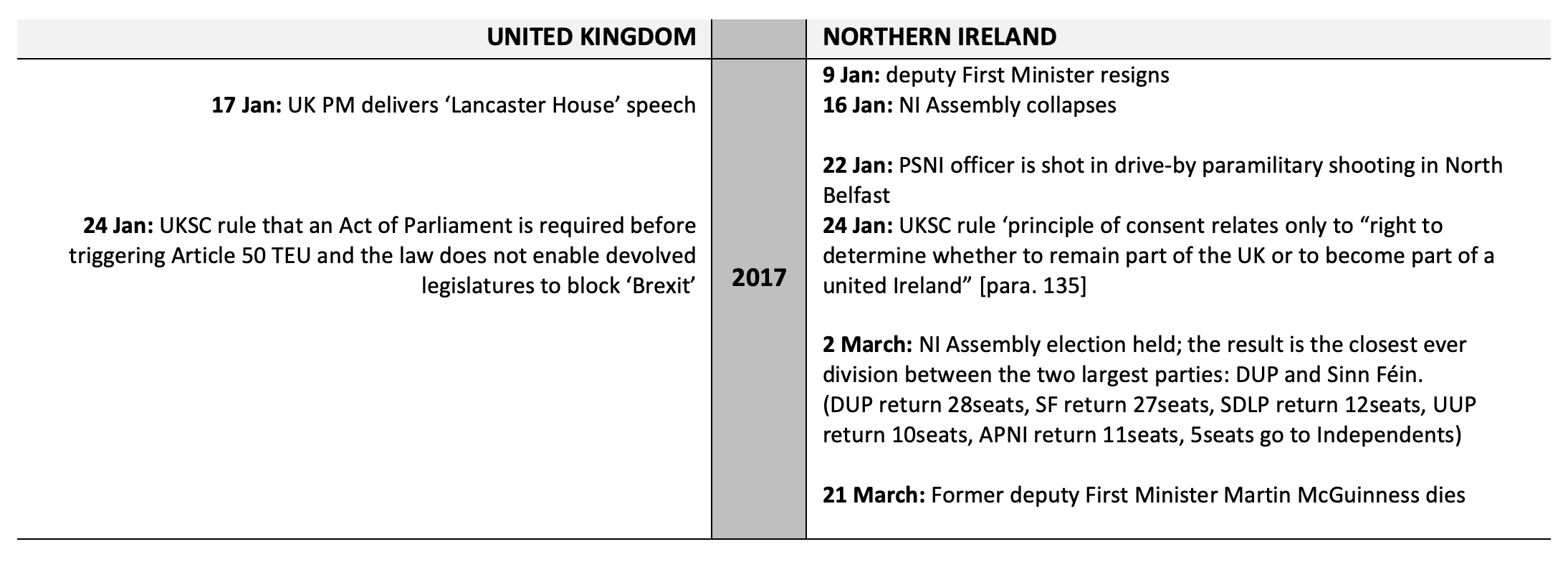

Notwithstanding its unique vulnerability to Brexit, Northern Ireland hardly featured during the UK’s EU referendum campaign. Related debates in Northern Ireland were also comparatively muted. As the timeline of events demonstrates, in the early stages of Brexit, unprecedented political turmoil in Northern Ireland was once again occurring on the margins of a wider political and constitutional shift in UK-EU relations.

The language of politicians at the time again implicitly excluded Northern Ireland. In January 2017, Theresa May sought to define Brexit. Proposing to speak for the people of the UK, the Prime Minister used her Lancaster House speech “to set out the reasons for our decision”; one of which was the distinctive political tradition of the United Kingdom. Mrs May contended:

we have no written constitutional settlement…only a recent history of devolved governance…[and] little history of coalition government…

Perhaps the Prime Minister counts 22 June 1921 as recent. It was the day the first Parliament of Northern Ireland was officially opened and therefore marked the first venture of devolution in UK history. Although less directly the Prime Minister’s vision of the unwritten constitution and limited experience of the coalition government was also arguably a misrepresentation in respect of Northern Ireland. In the case of Robinson in 2002 Lord Bingham and Lord Hoffman characterized the Northern Ireland Act of 1998, that gives legal force to the provisions of the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement, to be “in effect a constitution” for Northern Ireland (25; n19 [33]). Since 1998 Northern Ireland has been governed, albeit intermittently, by power-sharing coalition government under the innovative governing architecture outlined in the written constitutional texts of 1998. These aspects of Northern Irish history seem to challenge Prime Minister May’s depiction of British exceptionalism.

The Prime Minister’s implicit omission of the particularities of Northern Irish history were likely unintentional. It was, however, a fitting reflection of a long-standing convention in British political rhetoric whereby Northern Ireland has been excluded from visions of a Great British “us”. Northern Ireland seems to have resided in a curious kind of British political blind-spot; through Brexit however, this might be changing.

Northern Ireland’s rhetorical rise

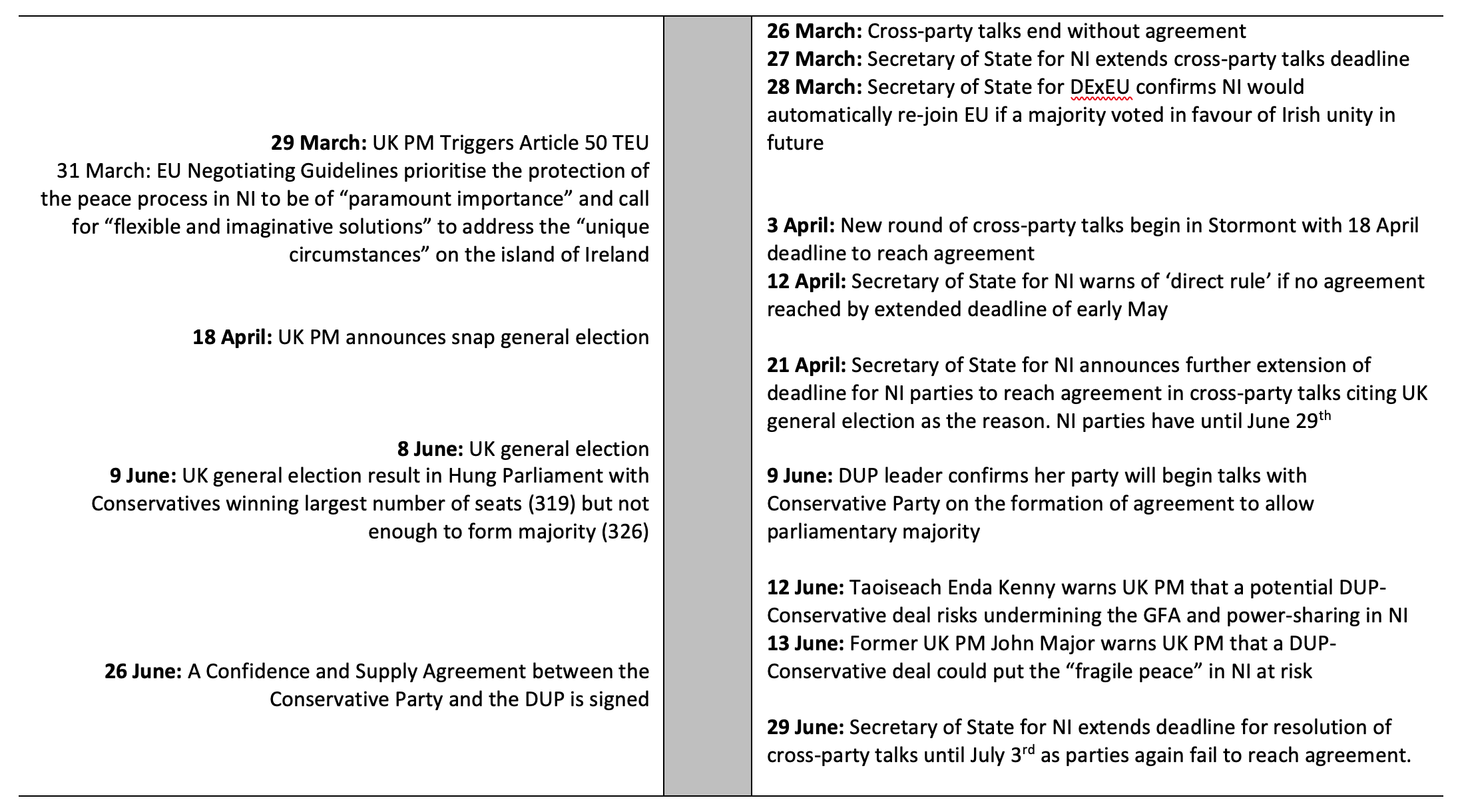

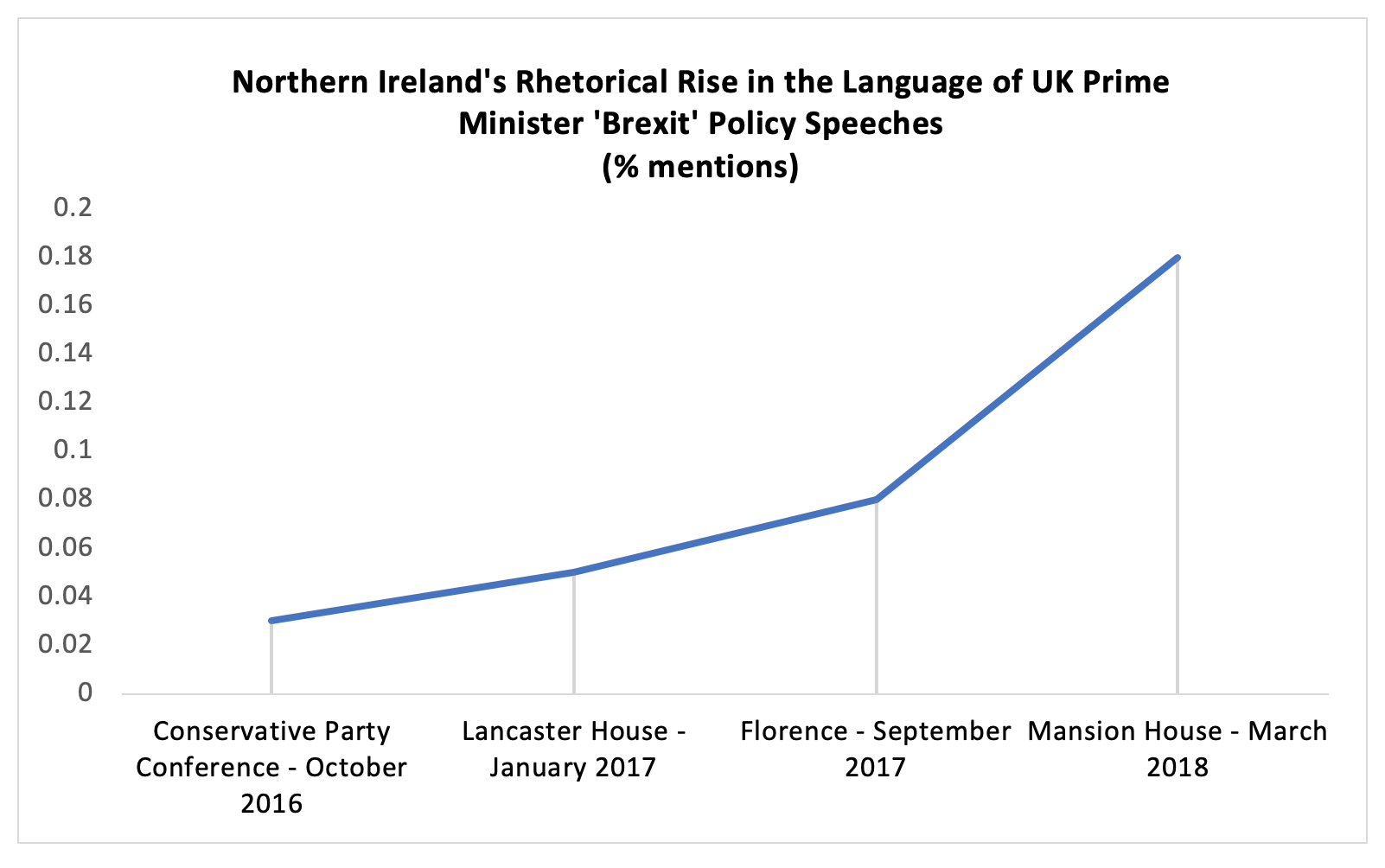

The potential difficulties presented by Brexit to Northern Ireland’s geographic, constitutional, political, economic, and societal structure, as well as its recent history of conflict, are now widely acknowledged. As Figure 1 indicates, following the outcome of the UK general election in 2017 and since the beginning of UK-EU withdrawal negotiations, the level of attention on Northern Ireland has increased significantly.

Northern Ireland’s multifaceted vulnerability facing Brexit; the EU27’s prioritisation of “the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland” as a divorce issue to be settled in the withdrawal agreement; and the unexpected outcome of the 2017 general election which led to the Conservative-DUP confidence and supply agreement have collectively enabled an unprecedented rise of Northern Ireland in the language of UK politics.

A new constitutional moment?

Successive constitutional moments on the island of Ireland have been preceded by periods in British political debate wherein the place has become synonymous with questions and problems. The ‘Irish Question’ debates of the early 20th century ultimately led to the partition of the island and the creation of Northern Ireland; the ‘troubling’ problem of the protracted conflict in Northern Ireland ultimately led to the constitutionally innovative Belfast/Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Notwithstanding the internal origins of the ongoing political stalemate in Northern Ireland, the primary catalyst for the re-articulation of the Northern Irish problem in the era of Brexit did not arise from internal discontent. It is arguably this fact that has enabled the mobilisation of civil society in Northern Ireland in ways that are remarkable in the history of the place. The prolonged lack of comprehensive democratic representation 848 days and counting) and the position of Northern Ireland as a pawn in mainstream British and European politics seems to be reinvigorating public political engagement. Northern Irish businesses and industry leaders have pledged to support the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement; peaceful protests and displays of public frustration – not least at the funeral of Lyra McKee; alongside nascent signs of new life in electoral politics are all hopeful signs in a place where political optimism is all too rare.

The lasting significance of the perennial problem of Northern Ireland taking centre stage in the Brexit drama is not yet clear; it is, however, an unfamiliar situation for all involved. Whether or not the shadow of Northern Ireland’s past proves long enough to reach those elusive “sunlit uplands” is not yet known. Whether or not the re-articulation of the problem of Northern Ireland and its tricky questions might lead to a new constitutional moment for the place is not certain. Arguably at this stage only one thing is clear – regardless of the impact of Brexit on Northern Ireland, this time more people will be watching…

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by Sinn Féin. Some rights reserved.

Lisa Claire Whitten is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University Belfast.

1 Comments