Very few British people know about restrictions on freedom of movement allowed under existing EU regulations. Yet when they learn about the EU’s “three-month rule”, two-thirds (64%) say it would provide “enough control” over EU immigration. And 67% say that they would support the introduction of ID cards if it meant the authorities could enforce restrictions applied in other EU countries. Tessa Buchanan (left), Lee de-Wit (University of Cambridge) and Alan Renwick (UCL Constitution Unit) discuss the findings.

Very few British people know about restrictions on freedom of movement allowed under existing EU regulations. Yet when they learn about the EU’s “three-month rule”, two-thirds (64%) say it would provide “enough control” over EU immigration. And 67% say that they would support the introduction of ID cards if it meant the authorities could enforce restrictions applied in other EU countries. Tessa Buchanan (left), Lee de-Wit (University of Cambridge) and Alan Renwick (UCL Constitution Unit) discuss the findings.

With an election widely anticipated before the end of the year, policymakers will be asking themselves again: “What do British voters actually want when it comes to EU immigration?” An opinion survey released today, carried out by YouGov on our behalf, suggests that despite growing polarisation there may be a hidden consensus on EU immigration across the political spectrum.

The nationally representative survey, conducted from 20–30 August, suggests high levels of support (71%) for a policy that would allow EU migrants to come to this country either to work or study (51%), or with complete freedom (20%). This position was backed by majorities of Conservative (71%), Labour (81%) and Liberal Democrat (78%) voters, and also by those who voted Leave (62%) and Remain (85%) in the 2016 referendum.

Fig. 1: Which of these policies regarding immigration from the rest of the European Union do you favour most?

N=1,005. YouGov 20–30 August 2019

Yet many people think the UK has no power to control EU immigration at all, and there is very low awareness about measures that could be taken under existing EU regulations.

About half of British people (47%), including a majority (58%) of Leave supporters and 62% of those aged 65 or above, incorrectly assume that the UK cannot impose any restrictions on EU immigration whatsoever, and only 20% know about the “three-month rule”, whereby the UK can insist that EU citizens who want to stay for more than three months must meet certain conditions, such as being in work, studying or having enough funds to support themselves.

Fig. 2: For as long as the UK is a member of the European Union, which of the following statements is correct? Please tick all that apply.

N=1,072. YouGov 20–30 August 2019.

When they are informed about the “three-month rule”, two thirds (64%) said that applying this restriction would “provide enough control over EU immigration”. Again, this position was backed by majorities among the Conservatives (61%), Labour (67%) and Liberal Democrats (81%), and by most Leave (58%) and Remain (76%) voters.

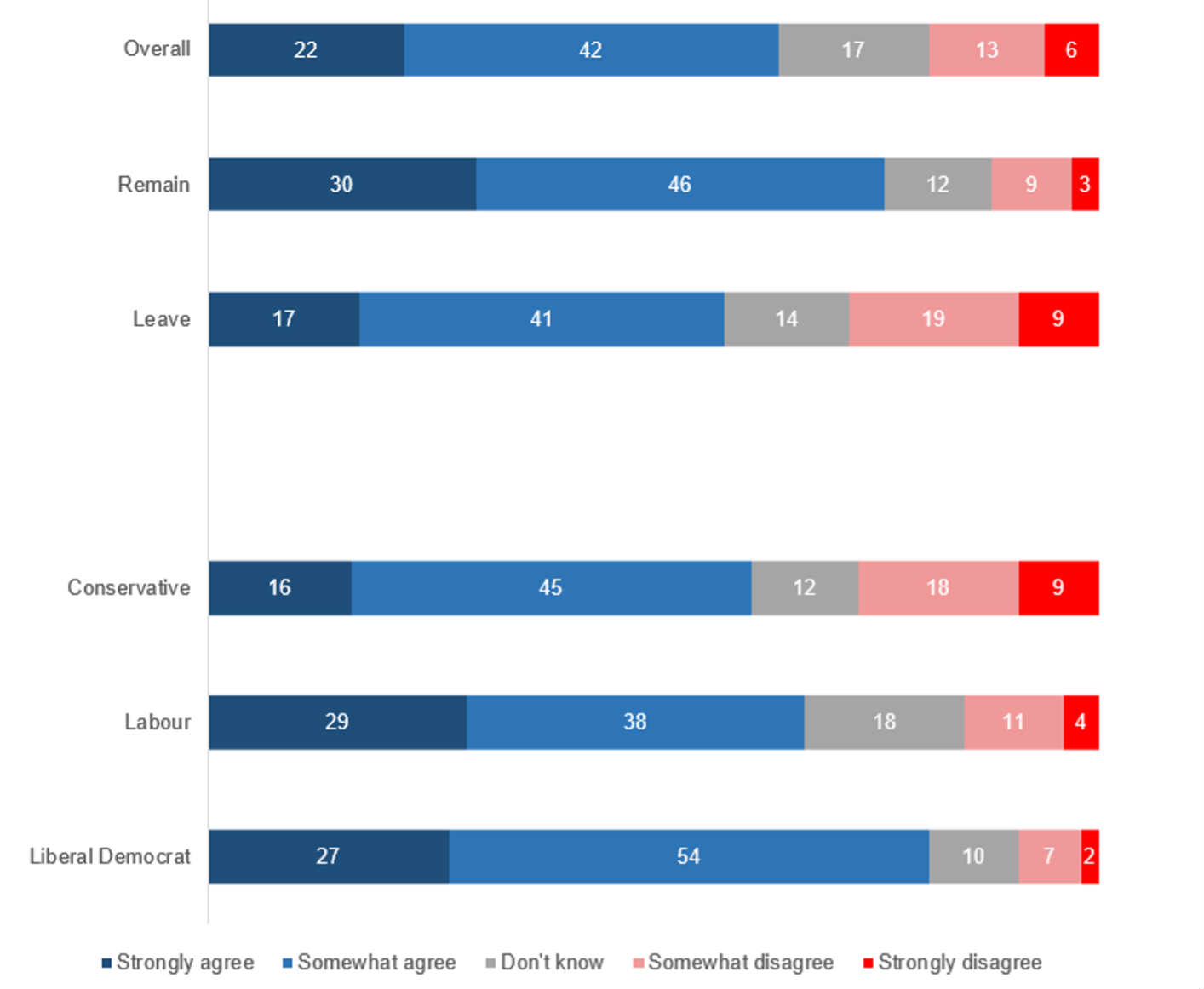

Fig. 3: Under EU regulations, the UK can insist that any EU citizen who wants to stay for more than 3 months must meet certain conditions (e.g. working, studying, or with enough money to support themselves). If the UK enforced these rules, to what extent do you agree or disagree that this would provide enough control over EU immigration?

N=1,072. YouGov 20–30 August 2019.

There are obvious logistical challenges to applying this rule in the UK. It requires the authorities to know where its EU citizens are, and ID cards have often been discussed in that context. This survey found that two thirds (67%) of Britons would support introducing ID cards for everyone in the UK if this “made it possible for the authorities to enforce immigration rules that apply in other EU countries”. This measure was backed most strongly by those aged 65 and older (82%), Conservatives (80%) and Leave voters (77%), but also by a majority of Labour voters (56%) and Liberal Democrats (59%).

Fig. 4: Would you support or oppose introducing ID cards for everyone in the UK if this made it possible for the authorities to enforce immigration rules that apply in other EU countries?

N=1,072. YouGov 20–30 August 2019.

Evidence from other sources suggests that these figures are not a one-off, and that opinion on these issues is relatively stable. In April last year, when YouGov asked whether people “would support or oppose the government making it compulsory for every person in the UK to carry an official ID card”, this was backed by a majority overall (57%), including most Conservative (68%), Labour (52%) and Liberal Democrat (53%) voters. And an identical question on people’s favoured policy preferences for EU immigration was asked by YouGov in July and August 2018. Overall support at that time was 70% for a policy whereby EU immigrants could come to the UK either to work or study, or with complete freedom.

The Citizens’ Assembly on Brexit carried out in autumn 2017 and led by UCL’s Constitution Unit yielded similar conclusions. With two weekends to fully debate the issues, no distractions, and access to neutral information and academic experts, most members of this nationally representative sample of British adults “wanted the UK to maintain free movement of labour with the EU, but to make greater use of controls that are available within the single market”. They also called for the government to “keep better data on migrants”.

After four years of Brexit debate, it is perhaps surprising that there has there been so little discussion of a potential compromise that appears to balance access to the single market and a level of control over EU immigration that is acceptable to the majority.

There would, of course, be important political barriers to such an option. Politics is path-dependent. Those who have staked their careers on abolishing free movement may have little interest in the small print of EU directives. And if ID cards are needed to achieve such a compromise, there is political baggage here too. A scheme adopted by the former Labour Government met with opposition from both left and right, before being abolished by then Home Secretary Theresa May in 2010.

Interestingly, in our sample, Leave voters were almost twice as likely to say that they “strongly support” ID cards (45%) compared to Remain voters (24%), which might help to explain why such a compromise hasn’t been more strongly advocated by those who campaigned to stay in the EU.

Stepping back from the current political dynamics, the results add to the growing body of research showing that even on highly polarising topics, there can be a surprising degree of agreement on individual policies. In the US, work by the ‘More in Common’ Foundation (set up after the murder of MP Jo Cox in 2016), found the majority of US citizens in favour of some gun control policies, and that most people supported certain pathways to US citizenship for undocumented children. The More in Common Foundation has also demonstrated that, in the US, Republicans and Democrats sometimes over-estimate the differences between them.

In the UK too, it seems the highly polarised nature of modern political debate may have obscured a potential consensus. This research suggests that British voters could be more pragmatic and open to compromise on EU immigration than widely assumed.

Notes

The YouGov survey was carried out between 20 and 30 September as part of an ongoing programme of research into attitudes towards immigration involving Dr Lee de-Wit, Director of the Political Psychology Lab at the University of Cambridge; Dr Alan Renwick, Deputy Director of UCL’s Constitution Unit; PhD researcher Tessa Buchanan; and research assistant James Ackland.

The programme of research is part-funded by grants from UCL’s Grand Challenges scheme and Cambridge University’s Psychology Department.

The 2017 Citizens’ Assembly on Brexit was organised by the UK in a Changing Europe initiative, and led by UCL’s Constitution Unit.

Home Office guidance published in November 2018 says: “EEA nationals who reside in the UK for more than 3 months must be exercising free movement rights. In doing so, they are classed as a qualified person.” The guidance says that qualified persons are defined as workers, the self-employed, self-sufficient people, students or job-seekers.

Job-seekers count as a special category under the “three-month rule” in that they are entitled to stay for an additional 91 days if they can prove that they are actively seeking work and have a “genuine chance” of finding it (the criteria for making this decision can include qualifications and language skills). After that time, the Home Office guidance says that they must produce “compelling evidence” of meeting these criteria such as a recent job offer. The guidance adds “If the person cannot satisfy this requirement then they cease to have a right of residence as a jobseeker.”

According to data from the Office for National Statistics, less than 3% of all economically active EU nationals in the UK are unemployed (2.9% compared to 3.7% for UK nationals, ONS, 2019).

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Tessa Buchanan is a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge Political Psychology Lab.

Lee de-Wit is a lecturer in the Department of Psychology at the University of Cambridge and director of the Political Psychology Lab.

Alan Renwick is deputy director of the UCL Constitution Unit.

Brits knowing how such laws are enforced when migrants are to be deported may undermine belief that these laws will work. It is not as if each of has to carry an ID card showing our status as Alien, Temporary Resident, Permanent Resident or Citizen

That aspect also deserves research when questioning acceptance of these laws.

These surveys avoid the main issue which is not about immigration per se but about the enormous numbers that have been coming to England – and not the rest of the UK, basically population growth at unwelcome, unsustainable levels. Who they are doesn’t matter either, just the numbers.