Twenty-two years ago, long before the word Brexit was coined, a proto-Euroscepticism was taking root in British politics. Ukip’s first incarnation and the relative success of the Referendum Party both played a part in the 1997 general election. Ros Taylor (LSE) looks at some of the campaign literature from that year.

Twenty-two years ago, long before the word Brexit was coined, a proto-Euroscepticism was taking root in British politics. Ukip’s first incarnation and the relative success of the Referendum Party both played a part in the 1997 general election. Ros Taylor (LSE) looks at some of the campaign literature from that year.

The 1997 general election is chiefly remembered for Tony Blair’s victory, which put an end to the Conservatives’ 18-year period in power. On the margins of the campaign, however, a viable Eurosceptic movement was beginning to take shape. Although it would be a long time before political parties were able to exploit the internet to campaign – a few Ukip candidates gave their email addresses on their leaflets – the election saw a new approach to campaign materials that anticipated the ubiquity of video in the digital era. Neither of the Eurosceptic parties that ran won a single seat, and they did not survive in their original form. But both developed narrative tropes that resonated with a section of the public, and a key demand – direct democracy – that ultimately enabled Brexit. The LSE’s archive collections offer a glimpse of these early Eurosceptic pitches.

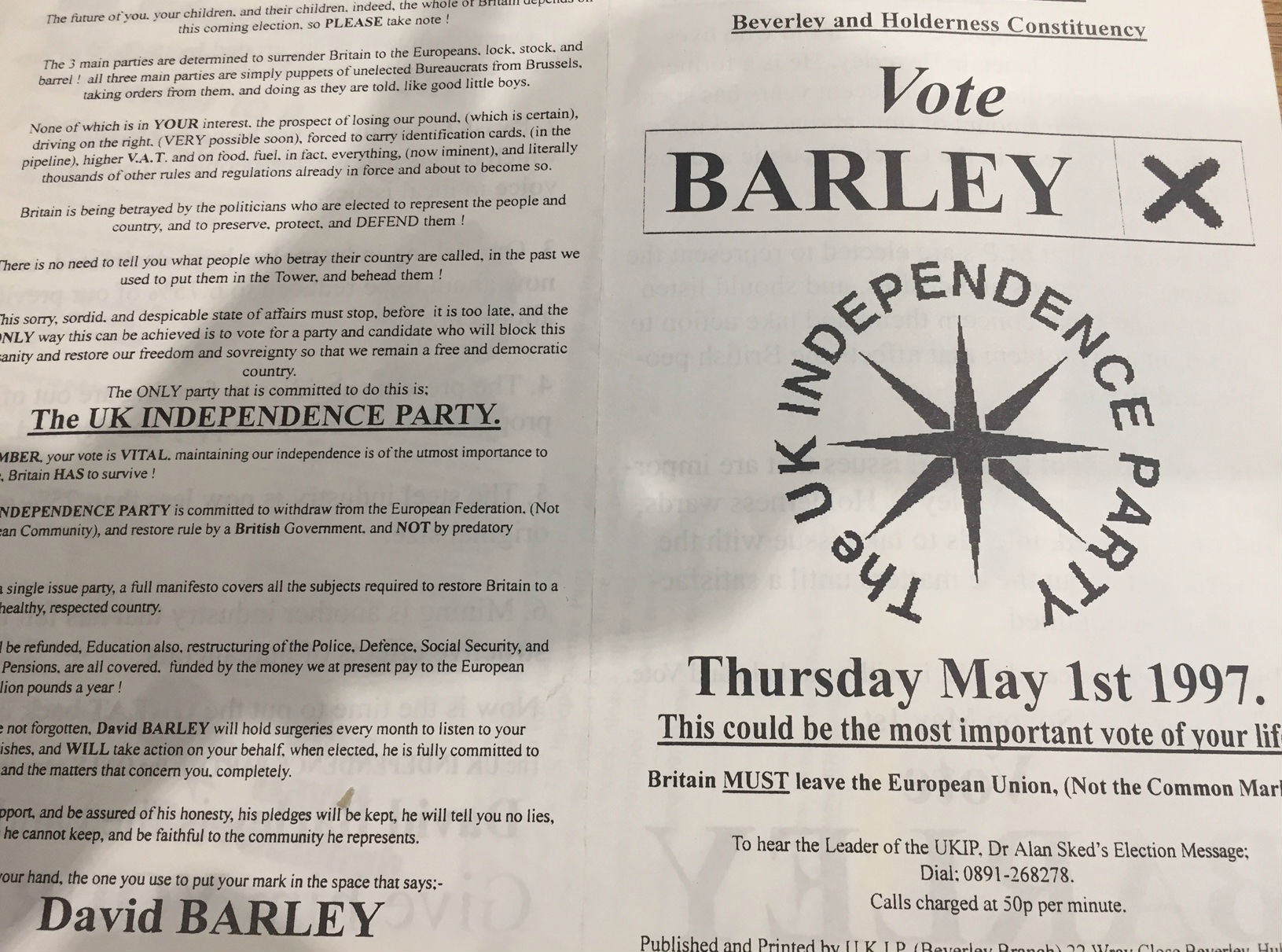

The Maastricht Treaty of 1993, which established the European Union as the successor to the European Community, had been a flashpoint for Eurosceptic feeling. Prime Minister John Major had clashed with his Eurosceptical MPs (the notorious ‘bastards’) and the Conservative MP for Reigate defected to the Referendum Party early in 1997, briefly giving it a seat in Parliament. He quickly lost his seat in the general election. Nonetheless, the party attracted nearly 812,000 votes – almost eight times as many as Alan Sked’s UK Independence Party (UKIP), which had been founded four years earlier and advocated complete withdrawal from the EU and a free trade agreement with the EU. However, as one of the local leaflets explained, this did not mean leaving the Common Market, which would nowadays put UKIP’s position towards the soft Brexit end of the spectrum. Strikingly, the language of ‘betrayal’ and treachery, which has been deployed by some Leave supporters since the 2016 referendum, was already evident in one local leaflet.

Sked was a lecturer in international history at LSE who had previously stood for Parliament as a member of the Anti-Federalist League, and UKIP was conceived as a non-nationalist and non-racist party. A number of its fundamental criticisms of the EU are familiar from Brexiters’ arguments today:

• Money saved on EU membership could be redirected to the NHS and schools;

• British law was being overruled in Europe;

• Burdensome regulation was afflicting small businesses;

• Britain’s fishing industry faced ‘destruction’ (‘we have just 10% of our original fishing rights’, said a Ukip leaflet);

• EU institutions were fraudulent and wasteful;

• Germany was the dominant force in the EU;

• As well as a police force (the first Europol director was appointed in 1999), Europe ‘wants its own army’ and would recruit Britons to fight for a cause they did not believe in;

• Britain had lost control over its national borders (though migration and freedom of movement per se were not, in 1997, identified as a problem; it was not until 2004 that the A8 countries joined the EU and Britain, along with Sweden and Ireland, opened up its labour market to their citizens).

A number of other concerns were not borne out and thus were not deployed by Brexiters 20 years later – such as the prospect of British taxpayers picking up the bill for the pensions liabilities of other EU countries, the imposition of VAT on children’s clothes, food, funerals and house purchases, and compulsory British membership of the euro.

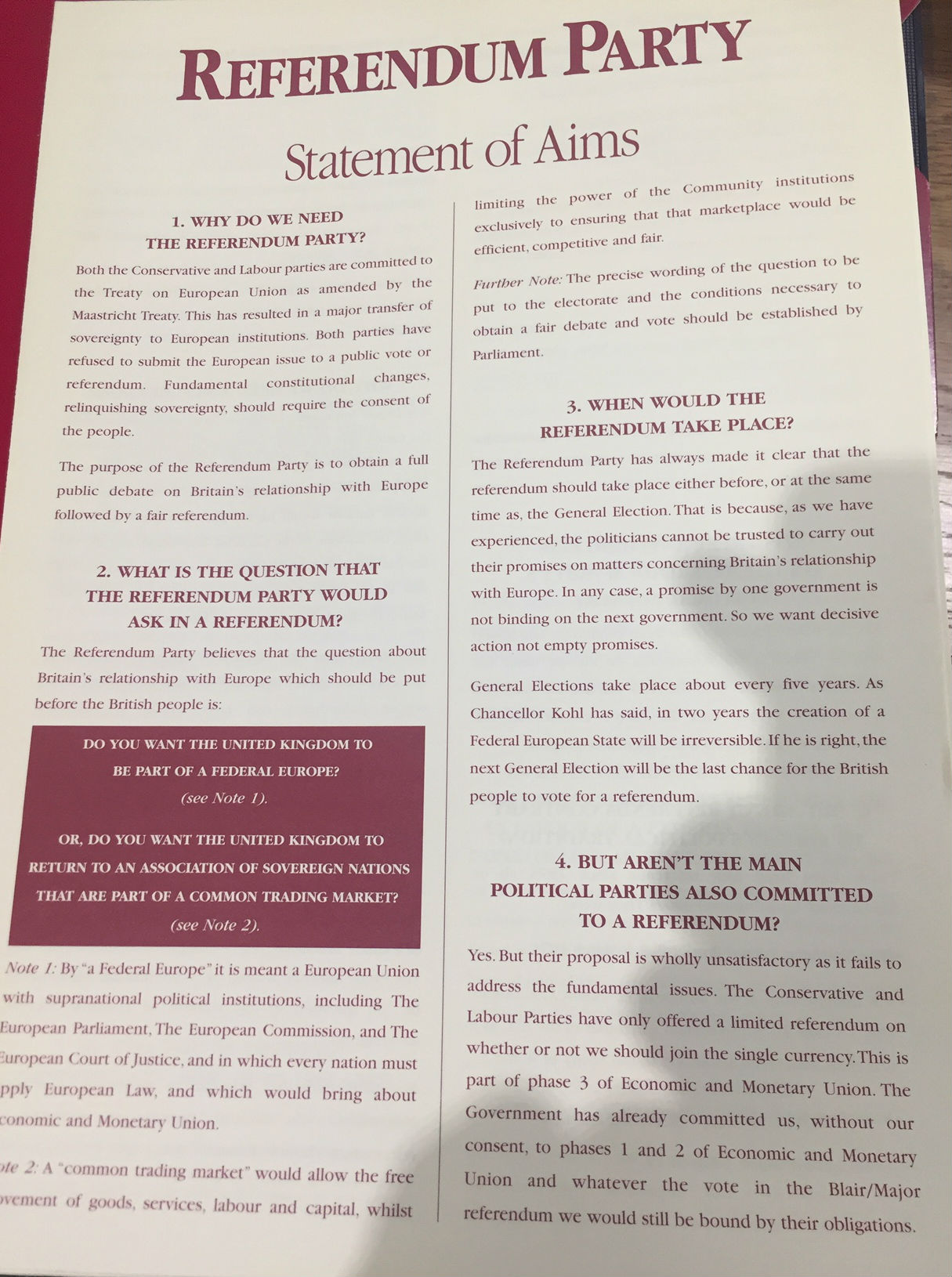

Unlike Ukip, the Referendum Party, which was led by Sir James Goldsmith and had been founded in 1994, did not advocate immediate withdrawal from the EU though it expressed similar scepticism about its merits. The Conservatives had promised a referendum in the event that the government decided to join the single currency, but Goldsmith wanted a referendum on British membership of the EU. Once that was secured, he promised, it would disband, ‘and you can vote once again for your usual party.’ The Referendum Party’s election leaflets had clear national branding. In contrast, Ukip’s logo was rudimentary and its materials varied from constituency to constituency.

‘In our view, the referendum should be multi-optional,’ Goldsmith wrote in an RP election leaflet. ‘The exact words should be determined fairly and constitutionally.’ His suggested question was to ask voters if they wanted to be ‘part of a Federal Europe’ and, secondly, whether they wanted to ‘return to an association of sovereign nations that are part of a common trading market’. Like Sked, Goldsmith’s preference was for the latter – or what would now be termed a soft Brexit that would preserve Single Market and customs union membership. The four freedoms would be preserved: the Community would merely ensure the Market was ‘efficient, competitive and fair’. The administration of the Single Market would presumably be entirely devolved to EU member nations:

‘There should be the strictest possible institutional control to ensure that this spirit of co-operation should never again be allowed to grow into the malignancy which produced Brussels and the other European institutions.’

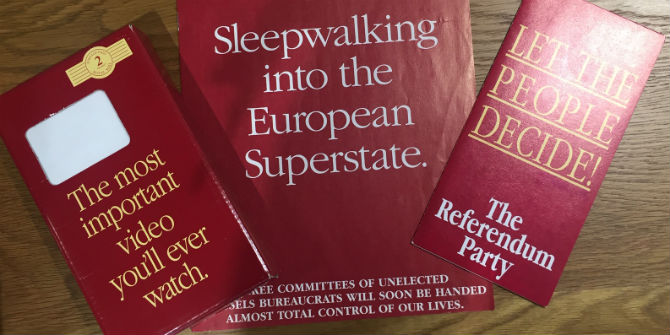

Goldsmith was dismissive of the mainstream media, but his financial resources enabled him to buy full-page advertisements in the broadsheets. The party spent more than £7.2m on press advertising in 1996-7. However, it was unable to persuade the Committee on Public Broadcasting, and later the High Court, to allow it more than one Party Election Broadcast (PEB). Goldsmith sought to overcome this problem by posting five million copies of an RP video, ‘The most important video you’ll ever watch’, to households. ‘The idea of a British political party distributing its own message to the electorate direct on video was entirely novel,’ wrote David Haas in the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television.

Goldsmith wrote the script for the video himself. It opened with sinister music (‘What you are about to hear will both surprise and outrage you’) and the looming prospect of Britain as a ‘mere province’ in a ‘European superstate’, led by Germany: ‘Into it will be merged up to 25 ancient European nations, including our own’, warned Gavin Campbell, the presenter of the BBC’s That’s Life programme. The Commission had ‘conspired’ to fool Britons into thinking that it was ‘just a Common Market’.

Ukip’s PEB opened with a similar warning that the UK was ceding its own sovereignty and would be ruled from Brussels, with the single currency administered from Germany. This broadcast was presented by Leo McKern, who played an elderly barrister, Rumpole, in a TV series of the same name. In the second part of the broadcast McKern discussed the party’s policies with Sked.

Neither party made a very significant impact on the public imagination: even the video mailshot, innovative though it was, could not overcome the hegemony of the established parties at a time when they all depended heavily on press, TV and radio coverage. But the Referendum Party’s performance ‘certainly contributed to the Conservative obsession with Europe’ (Carter et al., 1998), identified the referendum as a means of bypassing Parliamentary objections to Brexit and, along with Ukip, provided a template for Eurosceptic campaigning themes for years to come. Despite Goldsmith’s dislike of the media, the RP was able to tap into the anti-European sentiment of some newspapers and received ‘heavy media exposure’ (Carter et al.) given its status as a single-issue party. Indeed, the woman who headed the Referendum Party’s press office between 1995 and 1997, Priti Patel, went on to play a prominent role in Vote Leave and the Johnson government.

References

Carter, Neil; Evans, Mark; Alderman, Keith; Gorham, Simon, Europe, Goldsmith and the Referendum Party, Parliamentary Affairs, vol 51, issue 3, July 1998.

Haas, David, The Referendum Party’s Video Mailer Strategy, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol 17, no 4, 1997.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Ros Taylor is co-editor of LSE Brexit.

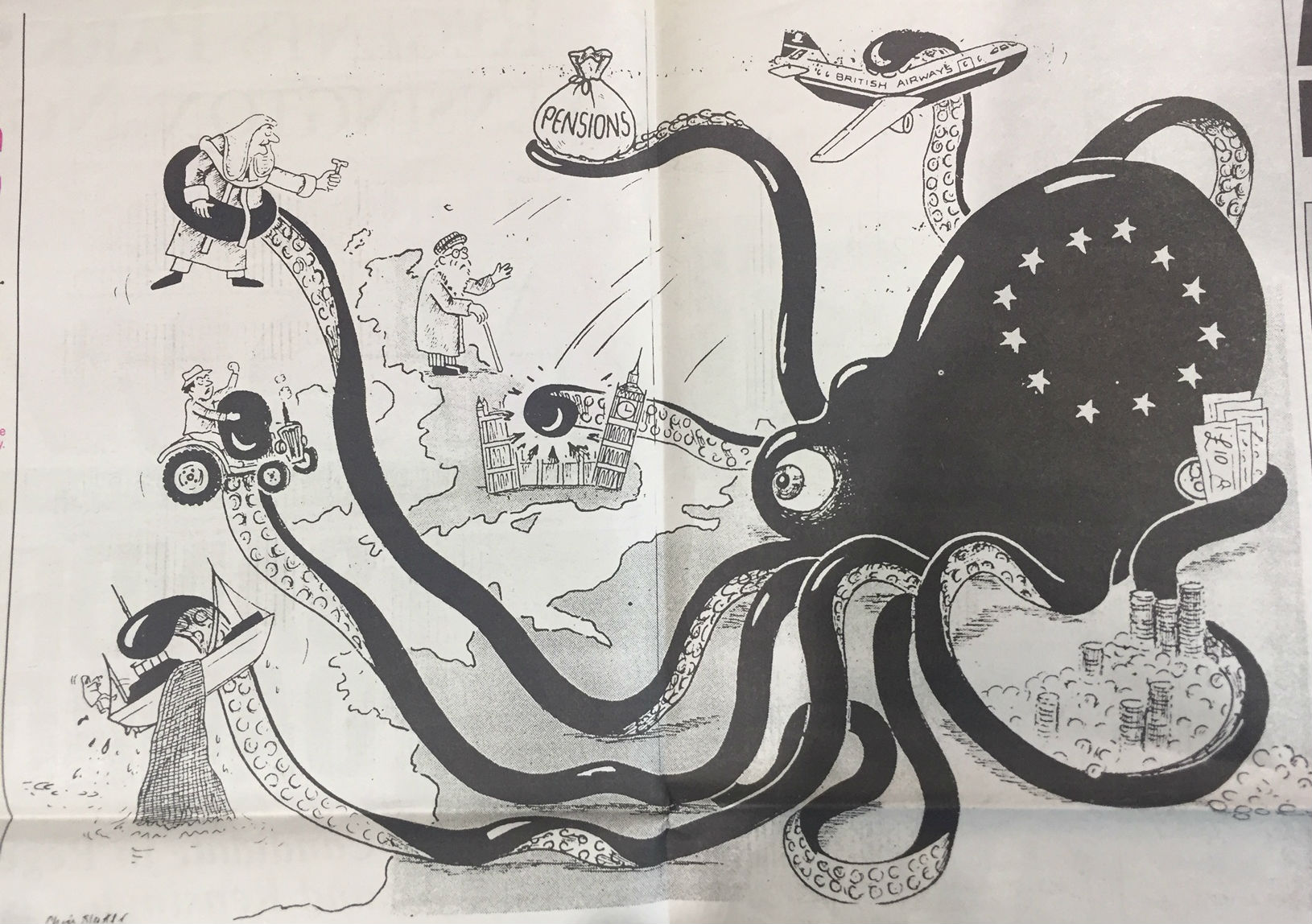

Fascinating, thanks. I like the list of 10 things that “A Federal Europe means”. As far as I can see, 22 years later 3 of them (1, 7 and 9) have happened. I don’t understand 5 which shows a stereotyped Frenchman (I don’t think you could do that today!) whose pension is being funded by British taxpayers. Of course people with good NI contribution records can claim pensions while living in Europe (or elsewhere), is that what the leaflet is referring to? Is it supposed to be a bad thing? 4 shows a shopping street with boarded-up shop-fronts crippled by European regulation; while indeed the High Street is in a bad way I think Amazon has far much more to do with it than European red tape. The other 5 predictions are clear misses.

It would be nice if the LSE digital library would put some of these leaflets in full online.

On pensions – no. There was a fear that some European counties would not be able to afford their own pension liabilities and that Britain would have to bail them out.

The octopus is crushing British Airways, and it is true that the EU-led liberalisation of air travel posed an existential threat to BA – it exposed it to competition from airlines like Ryanair. But BA is still around and customers have not complained much about the lower fares and greater choice of routes.

@Ros (on pensions): Thanks. Er, you mentioned that in the original article, sorry I missed it the first time.

Perhaps the interesting thing about the octopus cartoon, if it was typical of the anti-EU sentiment of the time, is that it shows how anti-EU sentiment has changed its tone over the last 20 years. I don’t think anyone these days talks about Brussels octopuses sucking in money from Scottish pensioners these days any more than they complain about the gnomes of Zurich. From what I can remember of the 2016 Leave campaign, the anti-EU argument was not about portraying the EU as malignant but as being incompetent or elitist. Even the “Breaking Point” poster (which I suppose was the low point) was not hateful towards the EU but towards people fleeing war zones trying to get in.

I haven’t done any kind of survey of newspaper headlines, but I can’t remember anything directed towards EU27 politicians to match the classic “Up Yours Delors” and “Foxtrot Oskar” (directed to Oskar Lafontaine) of 20 years ago.

The octopus is an anti-Semitic trope, though its use here may or may not be an echo of that. But the basic theme of Brussels ‘taking’ money from Britain is alive ans well – it was the theme of the infamous bus.

@Ros: perhaps the theme “The EU costs us a fortune” is the same for the octopus nicking the Scottish pensioner’s money and the Brexit bus, but the style of the rhetoric is miles apart. If the Brexit bus had not lied about the amount actually sent to Brussels, it would be difficult to object to the slogan at all.

The octopus picture unambigously shows a force based in Brussels, likened to a sub-human animal, which is attacking various popular British groups or institutions (pensioners, fishing boats, judges, Parliament or BA), taking their money away, to heap up the banknotes and coins within its own tentacles. Even if the author of the cartoon didn’t consciously reference anti-Semitism, the cartoon is at least referencing a kind of nationalistic populism which could easily lead to something like anti-Semitism.

Fast forward 20 years. I just don’t detect any trace that Michael Barnier or Donald Tusk or Jean-Claude Juncker or the EU27 as a whole are being popularly portrayed in that kind of way, fortunately.