The economic consequences of Brexit are overwhelmingly negative, estimate Swati Dhingra and Thomas Sampson (LSE). The more the UK distances itself from the EU’s economic institutions and policies, the greater will be the increase in trade barriers and the higher will be the costs of Brexit, they claim. This is the first of two blogs based on the CEP Election Analysis briefing on Brexit. It summarizes CEP research on the long-run economic effects of different forms of Brexit. The second blog will analyse how the referendum outcome has affected the UK economy so far.

Since the UK voted to leave the European Union in June 2016, Brexit has dominated UK politics and economic policy. Three and a half years after the referendum, the UK is yet to leave the EU, there is no certainty over if or when Brexit will take place, and the shape of future UK-EU relations is yet to be determined. Building on methods from earlier work on international trade, the CEP has developed a state-of-the-art model of international trade to analyse how Brexit will affect UK trade and living standards. This model has been used to study how different options for UK-EU trade relations after Brexit would affect the UK economy by analysing how changes in trade barriers affect UK trade, output and income levels in the long run.

Leaving the EU will introduce new costs of trade between the UK and the EU that make it harder for UK firms to do business with the rest of Europe. However, the extent to which trade barriers increase will depend upon the nature of the post-Brexit relationship the UK agrees with the EU.

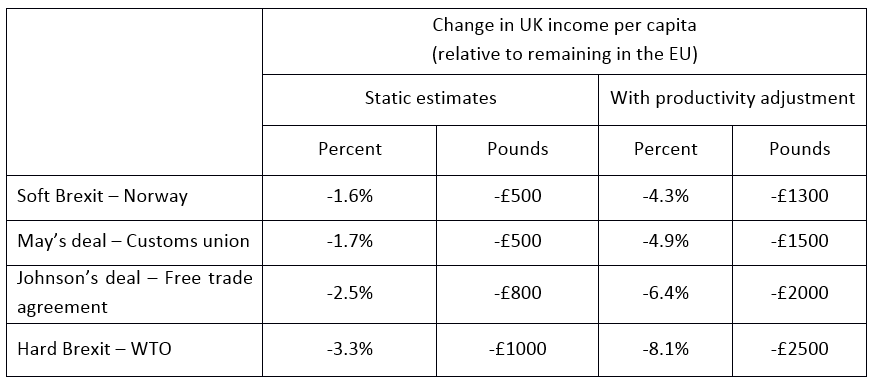

Table 1 summarizes the model’s forecasts for four scenarios: (i) soft Brexit – UK remains in the EU’s single market, but not its customs union; (ii) Theresa May’s deal – UK leaves the single market, but maintains a customs union with the EU; (iii) Boris Johnson’s deal – UK leaves the single market and the customs union and agrees a free trade agreement with the EU similar to the EU-Canada agreement; (iv) hard Brexit – future UK-EU relations are based on World Trade Organization (WTO) terms.

For each case we estimate the predicted effect of Brexit on UK income per capita ten years after the deal is implemented relative to an alternative scenario where the UK remains in the EU. We report both estimates from our static trade model and estimates that adjust for the effect of trade integration on productivity. Trade integration can raise productivity through increased competition, or stimulating innovation, but these effects are not included in the static model. The estimates that adjust for productivity changes are around two and a half times as large as the static estimates.

Table 1: Effect of Brexit on UK income per capita

Source: CEP calculations. See Dhingra et al. (2016), Levell et al. (2018) and Bevington et al. (2019) for details. Pound values calculated at 2018 prices using data from the ONS and rounded to the nearest hundred pounds.

Source: CEP calculations. See Dhingra et al. (2016), Levell et al. (2018) and Bevington et al. (2019) for details. Pound values calculated at 2018 prices using data from the ONS and rounded to the nearest hundred pounds.

Economic consequences of Brexit are negative

Table 1 shows that in all cases Brexit leaves the UK worse off economically than remaining in the EU. The worst-case scenario is a Brexit on WTO terms, which is estimated to reduce income per capita by up to 8.1 per cent. This is roughly double the cost of either a soft Brexit that keeps the UK in the single market, or a deal that maintains a customs union with the EU. The more the UK distances itself from the EU’s economic institutions and policies, the greater will be the increase in trade barriers and the higher will be the costs of Brexit.

The estimates in Table 1 do not account for the effects of Brexit on fiscal transfers between the UK and the EU, or for possible gains to the UK from striking new free trade agreements with countries outside the EU. However, even under optimistic assumptions, these effects would be much smaller than the costs shown in Table 1. The UK is a net contributor to the EU budget, but fiscal savings from Brexit are likely to be at most 0.3 per cent of UK income (Dhingra et al. 2017) and the government estimates new trade deals would increase UK output by at most 0.2 per cent (HM Government 2018).

Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal

The Conservative party is proposing that future trade relations with the EU should be based on a free trade agreement similar in scope to the EU-Canada deal. This would entail the UK leaving the single market and customs union, while maintaining tariff-free and quota-free trade with the EU for all (or almost all) products. Leaving the EU’s customs union would require the introduction of customs checks at the UK-EU border. In addition, goods would have to satisfy rules of origin requirements to qualify for tariff-free entry, and trade would be subject to the threat of anti-dumping duties and countervailing measures. Likewise, leaving the single market would lead to the introduction of new checks to ensure goods and services exports comply with the EU’s legal standards, and regulatory divergence will further increase trade costs if businesses need to split production lines for different markets.

We estimate that under a Brexit based on Conservative proposals, UK income per capita ten years after the deal was implemented would be up to 6.4 per cent lower than in an alternative scenario where the UK remains in the EU. The costs of a Boris Brexit are lower than for a WTO Brexit, but between one-third and one-half larger than for a soft Brexit or for Theresa May’s deal. This reflects the fact that Johnson’s deal envisions a future in which the UK is less integrated with the EU than under May’s deal.

Labour’s Brexit policy

Labour’s Brexit policy is ambiguous but involves seeking a soft Brexit that keeps the UK in a customs union with the EU and perhaps also in the single market. Once negotiated the deal would be put to a referendum, though it is unclear whether Labour would campaign for or against its own deal. To get an idea of the likely economic effects of Labour’s policy, we have analysed two options that maintain relatively high levels of economic integration with the EU. We find that the costs of leaving the single market while remaining in the customs union (May’s deal) are similar to the costs of leaving the customs union while remaining in the single market (Norway option). Under both alternatives, the UK is better off than under the Conservative party’s preferred option of a free trade agreement Brexit. In this sense, Labour’s Brexit policy is preferable to Conservative policy from an economic perspective.

Other parties

The Liberal Democrats, Scottish National party, Green party and Plaid Cymru advocate cancelling Brexit and remaining in the EU. Since all the Brexit options under consideration leave the UK worse off than if it stays in the EU, remain is the best policy in terms of Brexit’s effect on average income per capita in the UK.

There is a broad consensus among economists that leaving the EU will, in the long run, reduce UK living standards. But the magnitude of the economic costs will depend on what form Brexit takes. Our analysis finds that Conservative proposals for future UK-EU relations to be based on a free trade agreement would result in around a 50% higher drop in income per capita than a soft Brexit. Remaining in the EU would be the best economic policy while leaving on WTO terms would be the most costly alternative.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.