The full economic consequences of Brexit will not be realised for many years. But 21 months after the referendum, we can start to assess how the Brexit vote has impacted the British economy. Thomas Sampson (LSE’s CEP) summarises what we know so far.

Brexit is yet to happen, but the economic effects of voting to leave are already being felt. How is it possible for the vote to have an economic impact while the UK is still part of the EU? Economic behaviour depends not only on what is happening now, but what people and businesses expect to happen in the future. And the referendum changed expectations about the future of the UK’s economic relations with the EU and the rest of the world.

The shift in expectations has two components. First, uncertainty has increased. Even now, it remains unclear what exactly the UK’s relationship with the EU will look like after Brexit and how policymaking in the UK will change. This uncertainty makes businesses less willing to invest in risky new projects leading to lower output growth.

Second, the referendum led to a decline in the expected future openness of the UK to trade, investment and immigration with the EU. This has made the UK a less attractive destination for foreign investment and reduced the incentive for businesses to invest in expanding UK-EU trade.

The most immediate impact of the Brexit vote was on financial markets. The day after the referendum, the FTSE 100 stock market index fell by 3.8% and the pound depreciated sharply. Davies and Studnicka (2017) study stock price movements in the days following the referendum and find that companies with greater exposure to the UK and EU markets suffered larger share price falls than businesses with a more global focus. This suggests investors expected the consequences of the leave vote to be particularly severe for firms whose operations straddled the UK-EU border.

The stock market downturn was short-lived with investors benefitting after the Bank of England responded to the vote by loosening monetary policy in August 2016 through a 25 basis point cut in interest rates and renewed quantitative easing. However, the fall in the value of sterling was more persistent. Between 23rd and 27th June 2016, sterling depreciated by 11% against the US dollar and 8% against the euro and it has remained around 10% below its pre-referendum value ever since. The depreciation of sterling suggests financial markets have lowered their expectations of future UK economic growth.

Image by Agne27, (Flickr), CC Attribution 2.0 Generic.

Image by Agne27, (Flickr), CC Attribution 2.0 Generic.

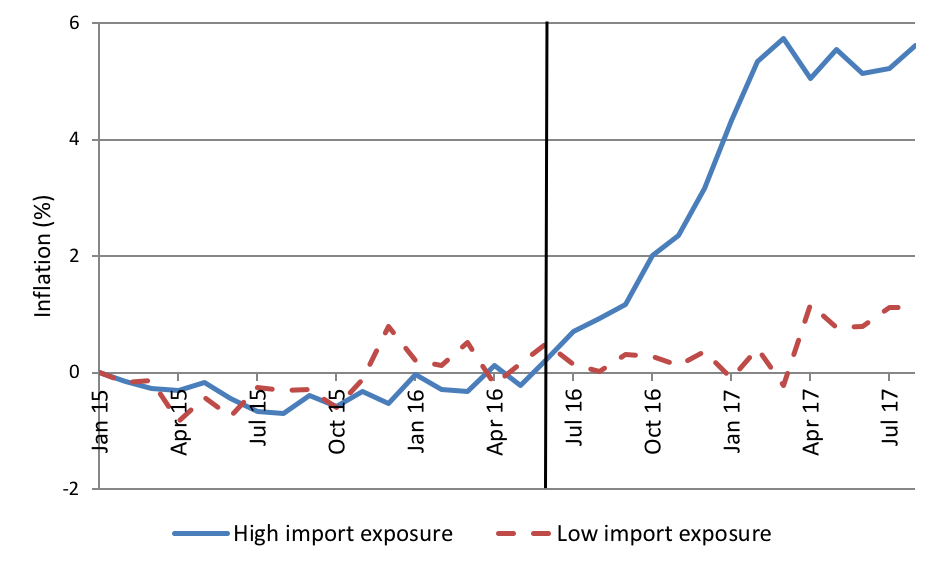

To do this, in Breinlich, Leromain, Novy and Sampson (2017) we study how product-level inflation since the referendum depends upon the share of imports in consumer expenditure. For example, tradeable goods such as fruit, wine and clothing have high import shares, while services like restaurants and hotels depend less on imports. If the Brexit-induced decline in the pound is responsible for higher inflation, we’d expect products with larger import shares to experience bigger price rises.A less valuable pound increases the cost of imports into the UK and makes UK exports to other countries cheaper. More expensive imports drive up the cost of living. Indeed, Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has risen dramatically since the referendum: from 0.4% in June 2016 to 3.0% in January 2018.

It would be a mistake to attribute this entire increase to Brexit though. Inflation has also increased in the US and the euro area over the same period, so we need to distinguish the impact of the Brexit vote from other factors that affect inflation, such as oil price movements and cost increases resulting from faster growth in the global economy.

And this is exactly what the data shows. Figure 1 plots inflation before and after the referendum for two groups of products: the top half of products in terms of import shares, and the bottom half. Following the referendum, there is a rapid increase in inflation for the high import exposure group, while the rise in inflation is slower and much more muted for the low exposure group. This demonstrates that the depreciation of sterling did indeed lead to higher inflation.

Figure 1: Import shares and inflation, 2015-17

Source: Breinlich, H., E. Leromain, D. Novy and T. Sampson (2017). “The Brexit Vote, Inflation and UK Living Standards”, CEP Brexit Analysis No. 11.

Source: Breinlich, H., E. Leromain, D. Novy and T. Sampson (2017). “The Brexit Vote, Inflation and UK Living Standards”, CEP Brexit Analysis No. 11.

After disentangling the effect of higher import costs from other factors that affect prices, we estimate the Brexit vote increased inflation by 1.7 percentage points in the year following the referendum. It would be wise to view the precise magnitude of this effect with some caution, but the increase is undoubtedly substantial.

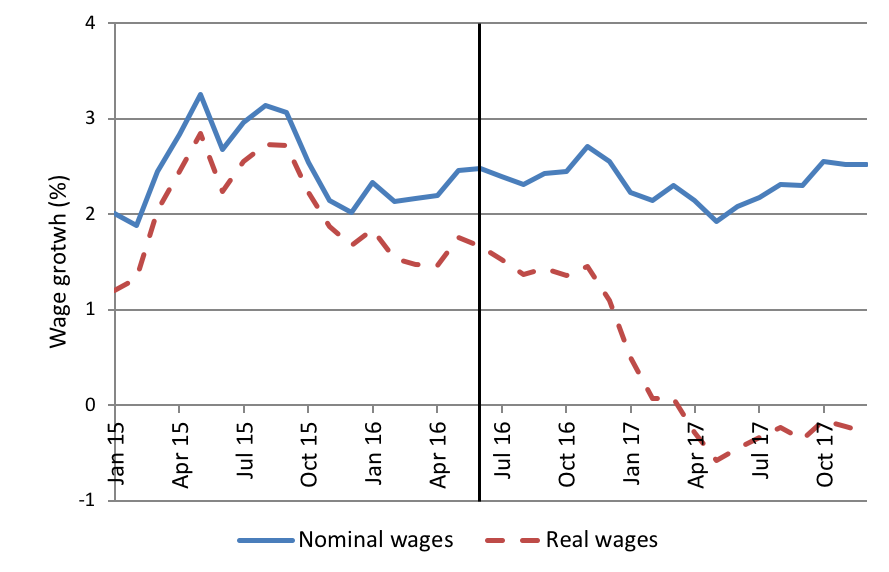

A rise in inflation does not necessarily make consumers worse-off if it is accompanied by higher incomes. But, as shown in Figure 2, nominal wage growth has not risen since the referendum. Consequently, higher inflation has led to a decline in real wages and a fall in living standards. Our estimates imply that, by June 2017, the vote to leave the EU was costing the average UK household £404 per year.

Figure 2: Nominal and real wage growth, 2015-17

Source: EARN01 February 2018, Office for National Statistics.

Notes: Wage growth is the percentage change year on year in the three month average of Average Weekly Earnings – Total Pay. Series KAC3 for nominal wages, A3WW for real wages.

Has the depreciation of sterling had any positive economic effects to offset the costs of higher inflation? By making UK exports cheaper, the fall in the pound gives British firms a competitive advantage in foreign markets, which could lead to higher exports. At the same time, the likelihood of future increases in trade barriers between the UK and the EU may make firms reluctant to invest in increasing their export capacity. And for firms with global supply chains, the fall in sterling also raises import costs, mitigating the competitive advantage of the depreciation.

When sterling declines, the value of Britain’s imports and exports measured in pounds automatically rises. But this does not mean the volume of trade has increased and, so far, there is no evidence that it has. However, trade flows are usually slow to adjust to exchange rate movements, so it will probably be another year or two before we know whether the fall in sterling has boosted exports.

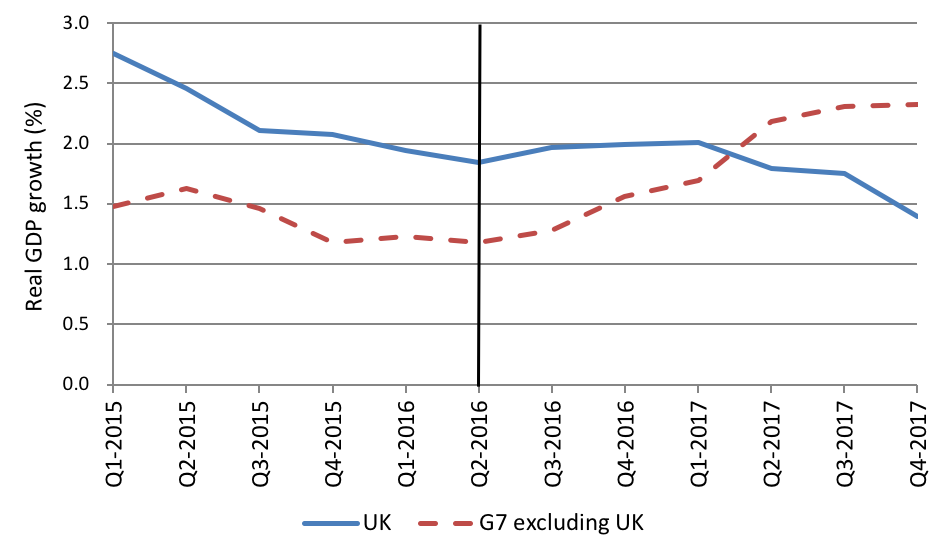

Researchers have also studied the impact of the referendum on GDP growth. Figure 3 shows GDP growth in the UK compared to the six other members of the G7 group of advanced economies. In the year prior to the vote, UK growth was 0.6 percentage points higher than the average for other G7 members, while in 2017 it was 0.9 percentage points lower. This is a crude comparison but does suggest that the referendum result reduced UK growth.

Figure 3: Real GDP growth, 2015-17

Source: Quarterly National Accounts, OECD and Statistics Canada.

Notes: Growth rate of real GDP (expenditure-based) compared to same quarter of previous year, seasonally adjusted. G7 excluding UK comprises Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States.

A more sophisticated version of this same approach has been undertaken by Born, Müller, Schularick and Sedláčaek (2017). They construct a control group of countries whose average growth exactly matches UK growth prior to the Brexit vote and then compare GDP growth in the UK and the control group following the referendum. They conclude that by the third quarter of 2017 UK GDP was 1.3 percentage points lower than it would have been if the UK had not voted for Brexit. This implies a decrease in output of approximately £500 million per week during the quarter.

Prior to the referendum, there was a broad consensus among economists that leaving the EU would, in the long run, reduce UK living standards. It is too soon to evaluate the accuracy of these forecasts and as time passes we will learn much more about how the Brexit vote has affected the UK economy. But even before Brexit occurs, the evidence on inflation, wages and output already shows that Britain is paying a price for voting to leave the EU.

A version of this blog was first published as part of the UK in a Changing Europe’s report Article 50: one year on. This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Dr Thomas Sampson is a Lecturer in the Department of Economics and a Trade Research Programme Associate at the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

1 Comments