More than half of Leave voters distrust the opinions of economists, and men, older voters and the less educated are more likely to mistrust them. Nonetheless, more than half of all voters say they want to find out more about the economic effects of leaving the EU. Alvin Birdi (University of Bristol), Ashley Lait (Economics Network) and Mark Cliffe (ING Group) warn that as the General Election approaches economists need to be extra careful to avoid accusations of political bias.

On the surface, it is encouraging that in the run up to an election which is bound to be dominated by Brexit, the ING-Economics Network Survey finds that there is a healthy interest in learning more about the economic effects of the UK leaving the EU. Over half of respondents expressed an interest in increasing their understanding of these effects. This desire is high across the sample but considerably higher among Remain voters (65%) than for Leave voters (49%).

This desire to increase understanding is heartening, but it stems from a troubling lack of knowledge about the impact of Brexit. Indeed, 42% say they do not feel they have a grasp on the economic consequences of the UK leaving the EU, while just under half (49%) feel they did have a grasp of these issues. The lack of understanding seems to be worsening, with 40% of the survey reporting it is becoming harder over time to understand the economics relevant for informed voting in elections and referendums.

It should be said that a knowledgeable electorate is not the only marker of successful democratic participation and political agency. This is especially the case where any shortcomings in relevant knowledge can be rectified through informed and trusted expert opinion. But if trust in experts is lacking there is a risk of undermining this important democratic input.

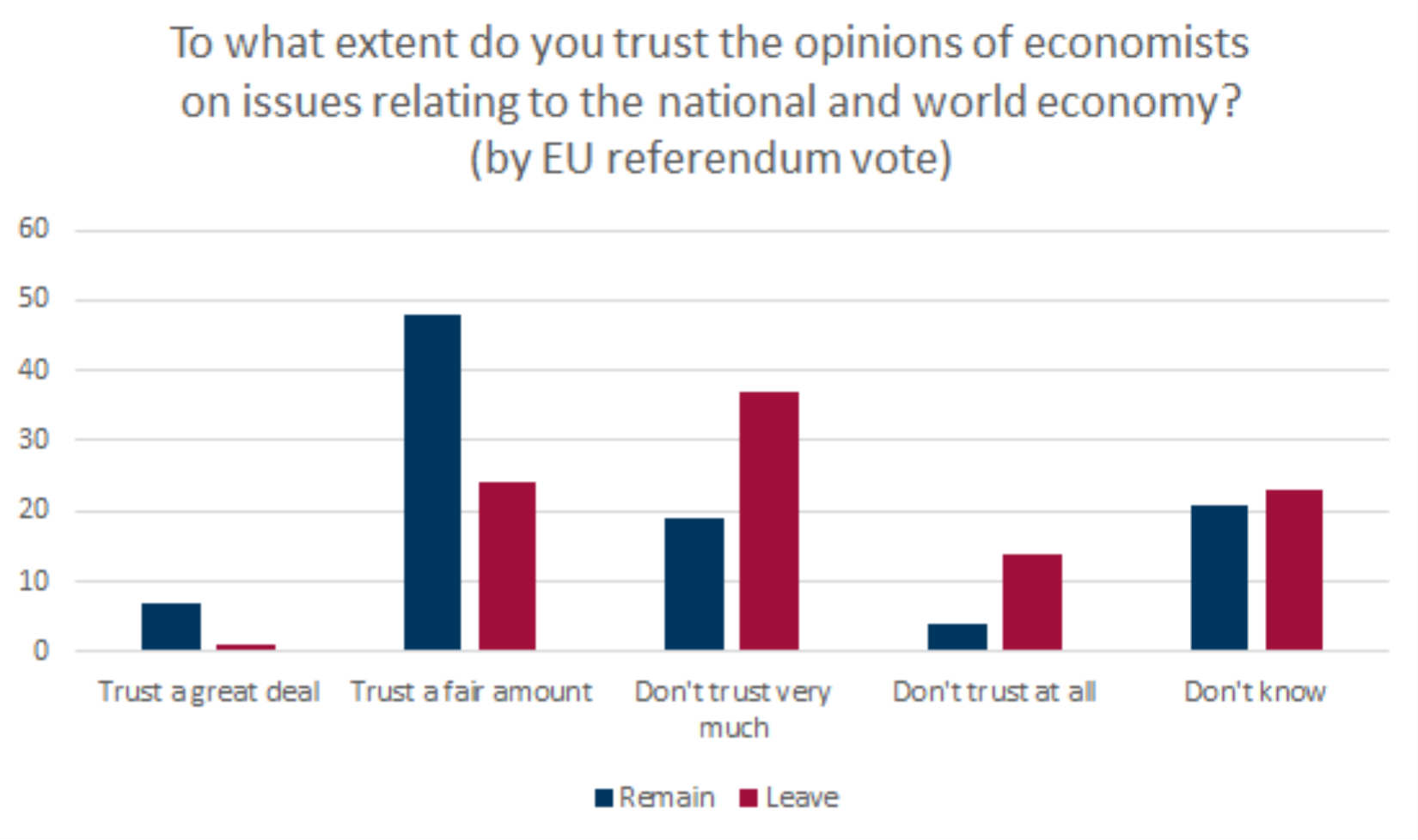

Sadly, our survey shows a considerable lack of trust in professional economics opinion, particularly among Leave voters. Significantly higher numbers of Leave voters (51%) distrust the opinions of economists on the world economy compared with Remain voters (23%). Worse still, this scepticism has intensified since the EU referendum, even among Remain voters. 45% of Leave voters have become more sceptical, compared with 28% of Remain voters. Most of the rest express either no change in their scepticism or no opinion.

We find that scepticism is also more prevalent among Conservative voters (46% compared with 31% of Labour voters), older people (over 40% of over 50-year-olds compared with just under a quarter of 18-49 year olds), men (36% compared with 31% of women) and the less educated (24% of people without GCSEs are much more sceptical compared with 11% of people with a degree).

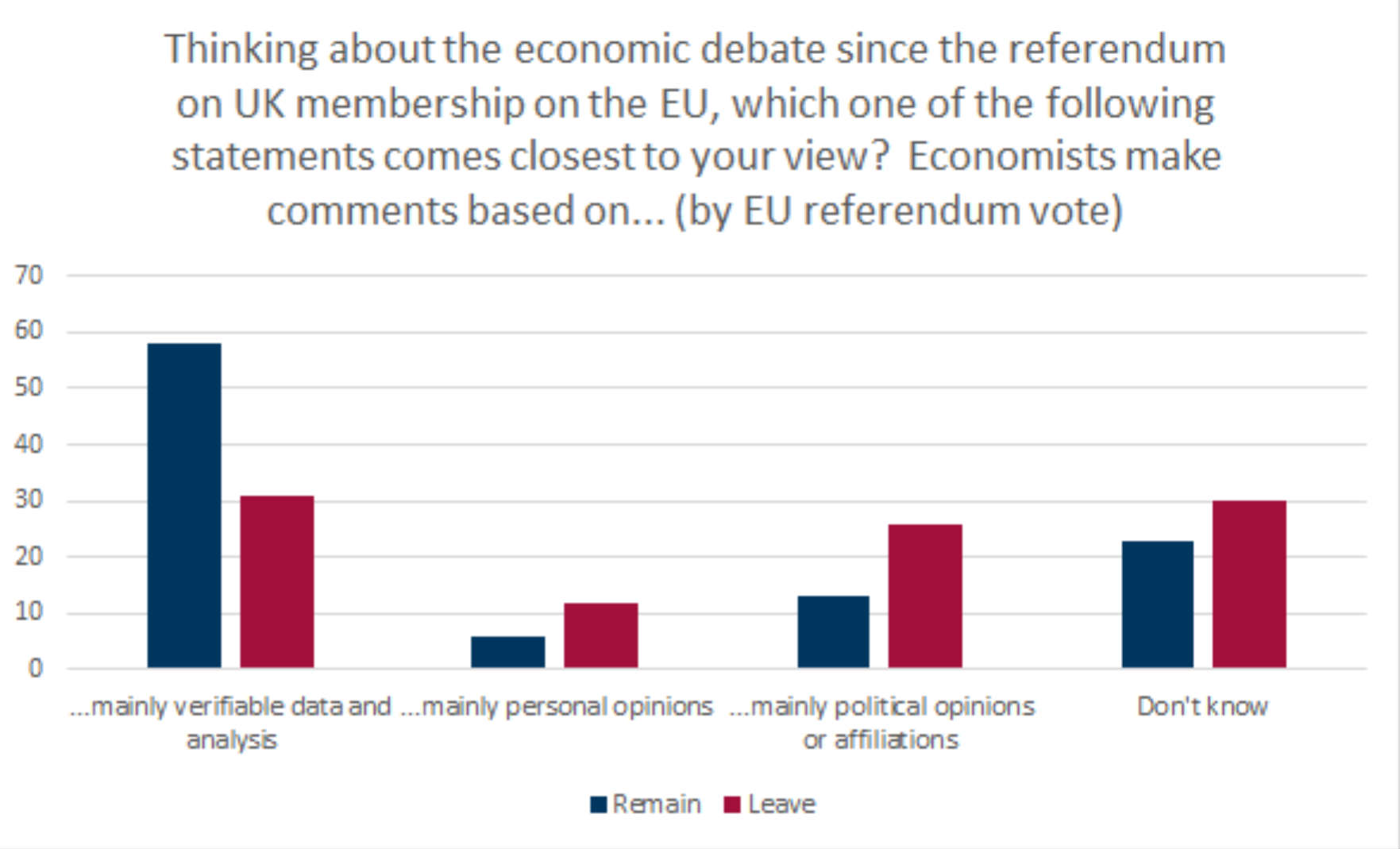

Indeed, this lack of trust is underlined by the finding that under a third of Leave voters (31%) believe that economists base their comments on verifiable data compared with over a half (58%) of Remain voters. Similarly, 26% of Leave voters believe such comments are based on political affiliations compared with 13% of Remain voters.

On the eve of an election, much of which will turn on economic issues, the mixture of a perceived lack of economic understanding, a desire to learn more economics and a distrust of those that can provide such understanding is a challenge for democratic participation. The fact that the lack of trust is skewed across political lines underscores both how divisive the EU referendum has been and how the consequences of that division present trust and communications challenges to economists. They need to be extra careful to avoid accusations of political bias in both the tone and substance of their analyses.

Note

The ING-Economics 2019 Network Survey of The Public’s Understanding of Economics is based on an online poll of 1,641 respondents from across the country conducted by YouGov. A previous cohort was surveyed in 2017. The first of a series of reports from the survey concentrates on public understanding, trust in economists and differences between Leave and Remain voters.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Seems like the electorate have a very healthy skepticism towards’experts’ in general and economists specifically. Not surprising given the electorate were warned that if they dared to vote to leave the EU Britain would face an instant recession. That recession didn’t occur so they are absolutely correct in being skeptical. The electorate are much better informed and willing to learn from their experience than many self-proclaimed experts would like to admit.

Forecasts are as the name suggests, and are useful as an indicator. All governments, and many other institutions use forecasts, also business. The notion a forecast is pinpoint accurate, is stupid!

Brexiteers during the 2016 referendum, used project fear, as a default position when asked questions, they did not have an answer for.

The aim of many politicians is to discredit opposition, or alternate views.

Many politicians adopt a mantra of suddenly when elected as an MP of having some sort of knowledge transplant. The reality is they are not some form of expert, nor do they poses the skills set required, find out their background and training.

The national debt continues to rise, business activity is reduced/moved location, growth is lowest in the G20, public services are on their knees, people are struggling to survive, the UK has just missed recession. If that is good economic performance, then god help us all.

What has occurred since the EU referendum has not been good for the economy. Surprise the economy has done better than expected (of the back of hard working individuals), is not that experts were wrong, damage has been done, but rather how hard British people have worked.

Brexit destination unknown, time to destination unknown, location unknown, terms and conditions unknown, policy no, hop and hope yes.

The economic predictions given are not far wrong the forecast for rain was correct, the rain is lighter than expected, that is all

If we look carefully at the question “Thinking about the economic debate since the referendum on UK membership of the EU”, the problem is that an economist can’t actually forecast the effect of Brexit without knowing how the negotiations will turn out, and that is something economic models are not able to forecast. I think almost all economists agree that trade barriers between developed economies are a Bad Thing, but they are not able to forecast whether the decisions of the hundreds or thousands of critical people involved in the UK, the EU or elsewhere will lead to significantly worse trade barriers or not. So if economists say that Brexit will lead to significantly worse trade barriers and so be bad for the UK economy, they are making assumptions from outside their area of competence. I think then it is reasonable to say that they are likely to be influenced more by their personal or political opinions than by verifiable analysis.

“Worse still, this scepticism has intensified since the EU referendum, even among Remain voters.”

I wonder if those Remain voters were the ones who were deterred from voting Leave because they were told that to do so would cause 400,000 to 800,000 of their fellow countrymen to lose their jobs within 2 years.