On 20 January 2020 Prime Minister Boris Johnson suffered his first defeat in Parliament. An amendment to the European Union (EU) Withdrawal Agreement Bill, moved by Liberal Democrat peer Jonny Oates with cross-party support, passed by 270 votes to 229. Lord Oates’ amendment wouldn’t break the EU Settlement Scheme, but it would fix it, argues Kuba Jabłonowski (University of Exeter).

The House of Lords recognised two fundamental problems with the EU settlement scheme which the amendment sought to address. Firstly, it replaced the current constitutive system – where individuals have to apply to secure their status – with a declaratory system. Such a scheme would confer status on all eligible individuals, though they would still have to register to receive an actual proof of status. Secondly, the amendment established an optional physical document available to all those applying to the settlement scheme. Currently, for the vast majority of applicants, the status is digital-only, although some are entitled to a physical document.

The government had previously indicated its strong opposition to any changes to the settlement scheme, and the amendment was roundly defeated two days later in the House of Commons by 338 votes to 252. It is however interesting how the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union Steve Barclay defended the government against changes that, in his words, sought to derail the EU settlement scheme wholesale. He said:

“This amendment would mean the successful EU settlement scheme in its current form would need to be abandoned, because there would be no need to register if people could later rely on a declaration that they were already in the UK. This would make null and void the 2.8 million applications and the 2.5 million grants of status that have already been completed. The government would, under this amendment, also be unable to issue digital status to EU citizens without also issuing physical documents, including to those already holding a digital status under the current scheme.”

The trouble is that none of these arguments is true. The amendment did not seek for the scheme to be abandoned or to remove status from those who had already applied for it. It only sought to remove the scheme’s hard deadline, which is currently set to 30 June 2021. The fundamental problem with the constitutive system is that once this deadline passes, “the status is not acquired” and lawfully resident persons will become unlawfully resident overnight. The deadline may and will be missed by many for a myriad of reasons, and this cliff-edge approach puts many applicants at risk. And generally, the more vulnerable an applicant is, and the lower capacity they have to access this digital settlement scheme, the greater the level of risk they face. Rather than approach this risk piecemeal, the Oates amendment sought to remove it by removing the hard deadline – while leaving most other parts of the scheme unchanged. Certainly, there was nothing in it that could invalidate the applications already made.

In addition to removing this cliff edge for applicants, the amendment spelt out one more change. It sought to give applicants to the settlement scheme a physical proof of their status, as currently the vast majority only receive digital status, which is widely mistrusted. A recent survey of well over 3,000 people entitled to settled status revealed nearly 90% of them were unhappy about it being only digital and wanted to have an option of a physical document too. However, the government refuses to engage with this. In his arguments against the Oates amendment the Secretary of State Barclay claimed physical documents and digital status are not compatible with the current system. This is mystifying for two reasons. Firstly, physical documents are already being issued to the settlement scheme applicants from outside the EU, EEA or Switzerland. Secondly, this would be in line with other immigration systems. For example, permanent residents of New Zealand can choose between free digital status and a residence document available for an extra charge.

Why does the government insist on a constitutive system, which will overnight remove legal status from the most vulnerable residents once the deadline passes? Why is the government so keen to emulate the Australian points-based system, but unable to copy good practice that combines digital status with residence documents in New Zealand? The debate in the Commons was short, and we did not learn why.

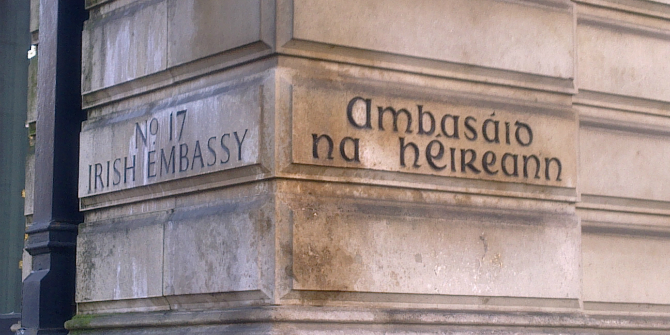

This post represents the views of the author and not those of LSE Brexit, nor LSE. Image copyright Jaggery and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

The main contribution made over the years by the House of Lords has been a much more detailed scrutiny of proposed legislation than takes place in the Commons followed by government acceptance of Lords amendments that made sense. It is already clear that this is one of the many norms which will be trashed by the Johnson/Cummings majority regime.

There is some justification for the cliff-edge. EU27 nationals living in the UK need to be motivated to get their status officially recognised now. The problem with a declarative system is that, in ten years, the paperwork may not be around any more, just as I think very many people (except obsessive collectors of utility bills and bank statements) would have a hard time proving where they were living in 2010. Data protection laws which require banks or utility companies to delete personal data once they have no legitimate interest in holding on to it make this even harder.

However I can’t for the life of me see why the government doesn’t back down on the physical document issue. Can anyone?

The advantage of a physical document is not just that it is handy for dealing with technology-averse landlords and employers. It also ups the stakes. Even if it’s only a letter on cheap headed notepaper which anyone can forge at home using their computer, anyone using such a forged letter risks not only being deported if found out, but being sent to prison.