The difficulty Theresa May and Boris Johnson had in winning the backing of MPs for their Brexit strategies illustrates the impact that ‘wedge issues’ can have on party politics, write Tim Heinkelmann-Wild and Lisa Kriegmair (Ludwig-Maximilians-University). As issues like Brexit cut across traditional party lines, they are highly likely to create intra-party divisions and make compromises difficult to secure.

It is a political science truism that individual actors’ rational behaviours often produce collectively sub-optimal results. The politics of Brexit within the Conservative party is a case in point. Brexit and the repeated failures to deliver it brought the Tories to a breaking point: it contributed to disastrous election results, led to the fall of Theresa May’s government, and triggered the loss of a parliamentary majority for the succeeding government under Boris Johnson, leading to an early General Election. How did this come about?

The seemingly irrational developments surrounding Brexit were the result of rational strategies employed by factions within the Conservative party in reaction to the divisive nature of Brexit. The key feature of wedge issues such as Brexit is that they cut across party lines, and thus hold the potential to spark intra-party divisions. Non-wedge issues give rise to conflicts along party lines because they map onto the dominant left-right cleavage that gave rise to western party systems. By contrast, issues such as migration, the environment or European integration do not map easily onto the left-right cleavage. When a political issue is a wedge issues for a party, the latter tries to avoid the topic. However, avoiding wedge issues is not always an option – especially for governing parties. When other parties highlight a subject, or when the pressure to solve a problem is high, governing parties have to engage with a wedge issue.

Enacting a policy that addresses a wedge issue is complicated by its divisive nature. When dealing with non-wedge issues, the government is in a strong position. It can count on the overwhelming support of its party and win over recalcitrant members of parliament (MPs) through concessions. With regard to wedge issues, the government is in a much weaker position and a conciliatory approach is not feasible. The number of MPs opposing the government’s policy is too sizable and any attempt to secure their support is likely to provoke resistance by other MPs that support the policy.

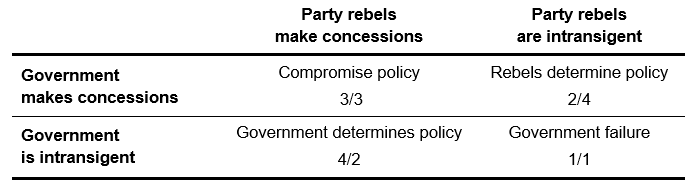

The ensuing actor constellation therefore resembles a game of ‘chicken’, pitting the government against party rebels opposed to the government’s preferred policy. In this intraparty game (see Figure 1), it is rational for both sides to commit to their preferred policy to force the other side to back down.

Figure 1: A game of ‘chicken’ within the governing party

To garner parliamentary support, the government will opt for an uncompromising strategy that we dub the ‘politics of intransigence’. It will refuse to compromise and try to enhance the credibility of its commitment to the preferred policy. For instance, it might present the policy as a take-it-or-leave-it offer that parliament may only accept or refuse. The government’s intransigence puts rebel MPs who oppose the government’s preferred policy in an uncomfortable position. They can either accept a policy they dislike or defeat their own government. To avoid this uncomfortable choice, they are likely to employ an intransigent strategy as well.

The more rebel MPs credibly commit to their preferred policy, the more the government finds itself between a rock and a hard place. It can stick to the proposed policy and risk government failure, or it can make concessions and alienate constituencies that favour their original policy. To avoid this uncomfortable choice, the government is likely to double down on its politics of intransigence to force party rebels to change their stance. While both factions would be better off compromising, it is individually rational for them to counter intransigence with more intransigence – even at the risk of escalating intraparty conflict and government failure.

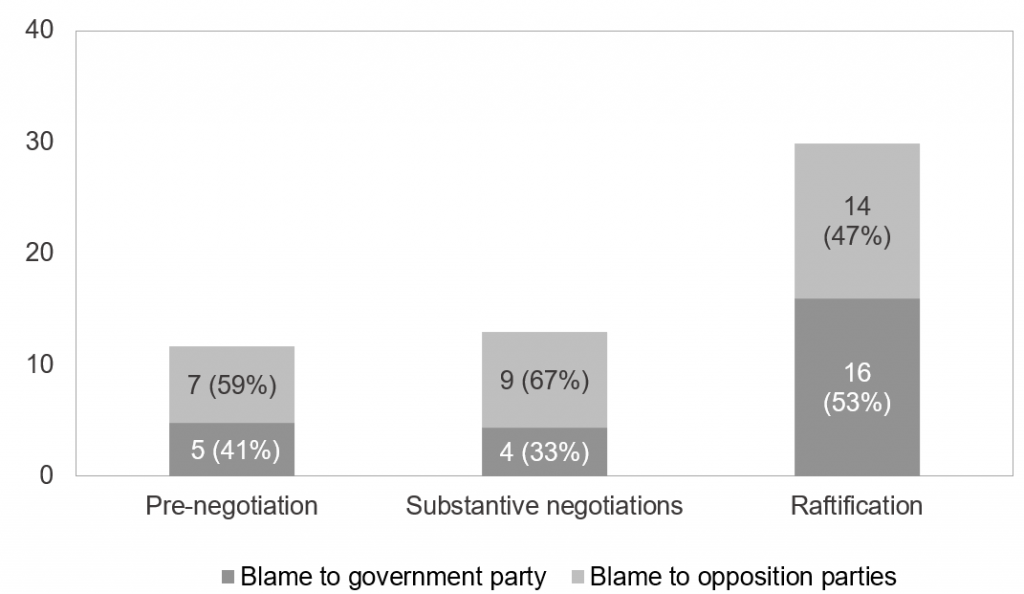

The politics of Brexit inside the Conservative party under Theresa May’s premiership were a clear example of wedge issue politics. The statements of Conservative MPs in which they attributed blame during the debates on Brexit in the House of Commons illustrated that the act of defining a Brexit policy drove a wedge through the party. While blame games in parliament are normally played between the governing party and the opposition, Conservative MPs also assigned blame within their own party to a significant extent. Figure 2 shows that before, during, and after the negotiation of the EU Withdrawal Agreement, more than a quarter of negative statements by Conservative MPs targeted members of their own party.

Figure 2: Conservative MPs’ blame attributions per 100 debate pages

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper (co-authored with Berthold Rittberger and Bernhard Zangl) at the Journal of European Public Policy

The divisive nature of Brexit gave rise to a game of ‘chicken’ between Theresa May’s government and Tory rebels, with both sides employing intransigent strategies. First, the government’s objective was to confront party rebels (and the Commons as a whole) with a take-it–or-leave-it offer, so that they would only be able to accept or reject the negotiated agreement. It therefore sought to keep parliamentary involvement at a minimum. Second, the government framed its agreement as the only policy alternative worth pursuing and ran down the clock to put pressure on parliament to approve the deal. The government also sought to keep on the table the two alternative outcomes – a ‘no-deal’ Brexit and no Brexit at all – that (at the time) found the least support among MPs. Finally, the government tied its hands to its own Brexit policy by publicly stating its unwavering resolve to stick to the agreement. It emphasised that there was no viable alternative to its deal.

In reaction to the government’s politics of intransigence, Tory rebels employed a similar strategy. Pledging rejection of the negotiated agreement, they sought to limit their freedom of action by declaring red lines. During the parliamentary adoption proceedings of the withdrawal agreement, Conservative rebels even began to claim that a ‘no-deal’ Brexit was preferable to the government’s agreement, thus committing themselves to an uncompromising position.

With no side willing to budge, both factions within the Conservative party responded to intransigence with more intransigence. This escalatory dynamic became visible in the share of blame attributions exchanged within the party. It increased from roughly one-third before and during the negotiations, to over fifty percent during ratification. The average number of blame attributions increased by over 200 percent.

In sum, due to the divisive nature of Brexit, the choice of a politics of intransigence was rational for the government and Tory rebels. Yet, it led to seemingly irrational and collectively sub-optimal results: a governing party unable to agree on a policy and a prime minister who saw no other solution to this impasse than to step down. Unfortunately, the politics of intransigence are likely to become a recurring challenge for western democracies. The rise of the new cleavage between communitarianism and cosmopolitanism implies a proliferation of divisive issues. To the extent that governments cannot avoid wedge issues, intra-party conflicts and thus the risk of policy and even government failure are increasing.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper (co-authored with Berthold Rittberger and Bernhard Zangl) at the Journal of European Public Policy.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE. It first appeared at LSE EUROPP and has been slightly edited to bring it up to date since first publication.

It could be decades down the track before the general public finds out exactly what has been cooking in and around Westminster since late 2015. So far, there is much about the last century and a half that is yet to come into the public domain. Indeed, there is much that will never divulged, or, if it does come out, can be filed under speculation due to it being impossible to prove. Secret societies are, and always have been, a fact of life in human society- at least so since the priesthood came into being thousands of years ago. In politics, there is always much going on behind the scenes which does not get a public airing. Much that is allowed out is speculation, half-truths, lies, constructive lies, conflicting statistics, the list is endless. On top of that much ado is about little or nothing to provide diversion and white noise.

The influence of international and transnational interests, whether vested or nascent, has also always been there. Much of this outside influence is not hidden, but, equally, many observers would guess that the hidden influence in national politics from abroad is considerable, if not much like the unaccounted-for gravity and energy in the universe- hence, huge.

In the matter of Brexit, there is not yet a true summing up attempted, that I know of. There is a diversity of opinion and facts, much of it contested or simply opposed without reason- at least without rational explanation. Cameron called the referendum and, backed up by a swath of worthies, pledged the government would implement the result, this once-in-a-lifetime decision. The rest is still history in the making. Both the Lords and the HoC were, at a pinch, 75% in favour of Remain, with a further 15 to 20% in favour of Brino. Whichever way you slice it, Parliament decided to stall and sabotage Brexit as much as possible and, failing that, go for Brino. At the moment, it looks about fifty-fifty for Brino on the one hand or an eventual Brexit taking several decades. In the process, the written and unwritten constitution has been shredded, legal and constitutional precedent upended. It could hardly be otherwise. Despite protestations to the contrary, much sovereignty had already been ceded to the EU, its derivatives, and to international busybodies acting in tandem with the EU project, but with global affairs uppermost on their agenda.

The diehard Remainers, remoaners so-called, have created a precedent, however, which may introduce a new element in the politics of parliamentary democracy, whereby the parliamentary input is transmogrified into a permanent tumult designed to stymie any kind of useful government doing anything worthwhile in the way of good governance and doing its job( with a view to private enterprise taking over at great, or greater, cost). Also in order to browbeat the electorate, or that part of the electorate insisting on democratic governance, into accepting a scheme of things not chosen by a majority and against the best interests of the nation-state and its citizenry, and edging out due process and legal/constitutional precedent while shoehorning into power extra- and ultra-national interests generally seen to be aligned with those powers pushing for globalisation and the relegation of the nation-states to a kind of coagulation of fiefdoms beholden to some lose globalisation alliance. Geopolitics in fact overriding national politics in national affairs.

There is, in all this, at least one novel element in the political life of the modern, or post-modern, western, European democracies.

Which is the introduction of mainstream- or establishment-sanctioned politically hyper-active and militant minorities who make it their business to sabotage democratic proceedings in order to effect a chain of groundbreaking and lasting changes in the political life of the nation against the wishes of a silent or decidedly less vociferous non-militant majority.