UK farmers have been promised that £3bn of EU direct payments, which come to end because of Brexit, will be matched until the 2024 General Election. The economic and social repercussions of the coronavirus pandemic mean this will be widely questioned. If those receiving these handouts remain aloof from those who fund them then the support will not be sustained. Farming needs to urgently regain the trust of a diverse population, argues Tony Hockley (LSE).

The magazine “Farmers Weekly” used an image of six white men to promote an event entitled “What does the future of farming look like?”. The event took place in National Inclusion Week. No irony was intended and the organisers insisted that they had tried to recruit women to speak. The ad provoked a social media debate over the rights and wrongs of seeking diversity in a sector dominated by white men. It prompted the Food, Farming & Countryside Commission to launch an online list of potential expert women, compiling more than 100 within 24 hours.

Male, pale and stale, it seems. 🤦🏻♀️ #futureoffarming pic.twitter.com/5Oib4qcFVe

— Emily Norton (@emilymnorton) September 25, 2020

Like many working in public policy, I cannot recall the last all-male panel at a mainstream event. I suspect that most would also agree that the change has been for the better. It is now the case that most men who would bring value to a policy event will decline an invitation to participate in one that is comprised entirely of white men of a certain age. As someone who is also active in the countryside, as a New Forest commoner, I also see a huge gulf in social norms.

The Farmers Weekly event is symptomatic of the challenge facing the countryside. Decades of EU subsidy, now mostly linked only to land area, have left the countryside with no real need to maintain any connection with the wider population. Divisions in current debates around the countryside reflect this disconnect, and the coronavirus pandemic has fed this division. Much of rural England voted heavily for Brexit. Taking back control of farming subsidies also means a stronger, more visible link between those who fund them and those in receipt.

This year has shown what happens when a population cut off from the countryside are forced to staycation and have nowhere else to go. Decades of failure of engagement have led to huge damage to precious sites for nature. From the pristine ponds and biodiverse grazed heaths of the New Forest in the South to the summit of Snowdon, some of the UK’s best sites for nature have been driven over, dumped on (in all senses), and burnt by disposed single-use barbecues. It is hard to blame the families involved, when so little has been done to engage for so long.

There is an opportunity to change this after the pandemic and outside the Common Agricultural Policy. Farmers must be willing and able to engage and to welcome renewed interest in our own countryside. Appreciation of nature and fears for its loss and for climate change are high. But few seem to connect these fears with the UK landscape, or with our own behaviours. We seem to worry more about the fate of the pangolin than the fate of the hedgehog, the adder, or the curlew. It is, of course, easy to blame others in foreign lands or faceless corporations, rather than look closer to home.

The Agriculture Bill lists ten “public goods” that can receive taxpayer support under the post-Brexit regime. The second of these is: “supporting public access to and enjoyment of the countryside, farmland or woodland and better understanding of the environment”

This seems surprisingly ignored in the discussion about future farming support. it needs to be a priority, not an afterthought. It is not something to be left to agencies and charities, but for everyone in the countryside. Indeed, if farmers do not become a partner in this work then they will see rural support diverted to those who will as “public money for public goods” takes over from land-based support. Despite the alarming damage to precious landscapes in 2020, a warm welcome needs to be the default approach, not the “Keep Out” sign. This will be a far cry from the insular mentality of the CAP, where land occupation counts more than anything.

Outside the CAP the UK can now invest properly not only in restoring nature but also in building an understanding of it and in helping everyone enjoy the countryside sustainably. Inside the CAP those who would like to do more have had to rely on the National Lottery to support local, time-limited projects. The Agriculture Bill offer the chance to scale up; The Heritage Lottery Fund has, for example, allowed New Forest commoners (including the author) to create a free toolkit which local primary schools have incorporated into their curriculum. This is helping re-connect the next generation to the countryside on their doorstep, and its special nature sustained by centuries of common grazing. But this is a drop in the ocean in a national park that is Britain’s smallest, has the highest proportion of SSSI-designated habitats, and which sees 15m visitor days a year. At the national level, the 2020 announcement of a new GCSE in Natural History is an important step in the same direction.

Education does, of course, take time. There is no silver bullet. In the short term, it will be the engagement within the countryside and breaking down barriers and hostilities that will make a difference. Without much greater inclusivity and engagement damaging behaviour will only get worse. Then those who access the countryside for the first time will only see barriers, warning signs, and policing. It will be just as important to engage with those who do not enjoy the countryside.

It is too easy for those of us who benefit from regular countryside access to fail to understand the psychological and behavioural barriers to those who do not and who are often visibly “different”. The Glover Review of designated landscapes highlighted this collective myopia, reflected in appointments to our national park authorities. Landscape conservation has become insular and process-driven. Politicians cannot deliver adequate public funding unless the population at large appreciate the need and feel the value.

That is why, even from a position of pure self-interest, it is deeply dangerous for discussions about the future of farming to lack diversity. It not only excludes half of the population by gender but also ignores wider demographic change amongst the taxpaying population: The proportion of the “White British” population in the UK is declining. The proportion of the population who are not White British or Irish is forecast to continue to grow, from 17.5% in 2016 to almost 40% over the next 40 years.

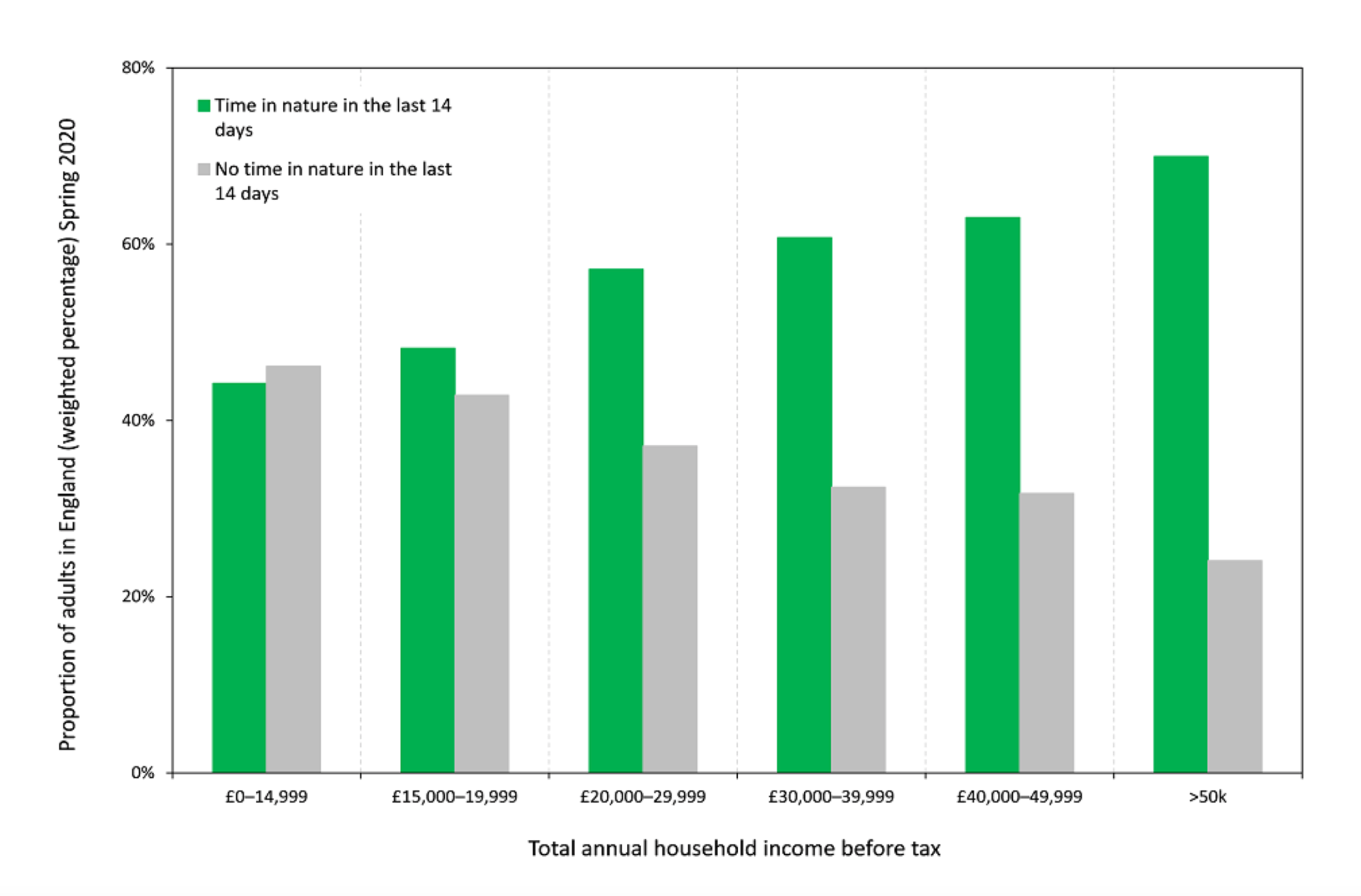

There is, of course, also a strong moral obligation to change. The events of 2020 have added emphasis to this obligation. Ethnic minorities in the UK and disadvantaged groups of all ethnicities have suffered disproportionately during the pandemic. Many of the towns and cities worst hit by COVID-19 are on the doorstep of incredible landscapes, but engagement is low. The pandemic has drawn attention to the health benefits of regular access to green spaces and of a deeper connection to nature. The People and Nature Survey for April to June 2020 revealed a deeply worrying divide in access to nature even when outdoor exercise was one of the few permitted activities during the coronavirus lockdown.

Figure 1 People & Nature Survey (30 Sept 2020)

It is often said that there is no need to worry about people who do not wish to enjoy the countryside. This ignores what we know about the constraining effects of social norms and expectations, human fears of being “out of place”, and also what we know about the advantages to wellbeing of green space and connections to nature.

Anyone who doubts that the countryside has much more to do on engagement would do well to read a blog by the earth scientist Dr Anjana Kathwa for the Council for National Parks. The future of farming after the pandemic and after Brexit must be very different from the past. Restoring nature on farmed land will require very different practice. This will be impossible to achieve without a linked shift in public expectations around food and countryside aesthetics (nature and tidiness do not go hand-in-hand). Behavioural science will have much to add in making this transition, building common cause for wellbeing, nature and climate. Messengers matter, as well as the framing of the message. A small effort on rural diversity is more important than it might seem to those most involved in the discussion of the future.

The change that needs to happen will need combined effort, engaging “town” and “country”. Diversification of farming practice will need to be matched by diversification of culture if the general public are to be expected not only to put their money into the countryside’s public goods but also prioritise support for domestic farming within future trade deals.

This is no small ask given the scale of the challenge of restoring the public finances after the pandemic and the very real risk that agriculture trade will be a spanner in the works for post-Brexit trade deals. There will certainly be no shortage of alternative and very popular uses for £3bn a year of public money, and deep resentment if the demands of an apparently reclusive and subsidised group jeopardise jobs. The future of farming really is a choice between diversity or decay.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Oh dear, here we go again with the “disadvantaged” and “white male dominated” theme. Covid has brought misery to everyone and the idea that certain sections of the population who are deemed, by this article (and other outlets), to have suffered disproportionally because they are in some way deemed to be disadvantaged, is offensive to every single person, group and other who has lost someone, their job, their home etc.

You seem to have balanced your distaste for those themes with a comparable readiness to take offence.

Part of a concerted and coordinated effort akin to a declaration of war on the family farm in the UK. The corporate- and big landowners and city investors will be fine. In fact, they have been fine for a long time. How convenient that the Farmers Weekly threw the woke academicians and gender obsessed racist progressives an easy ball to hit to hit off the next round of campaigns to further dislodge real farmers from their land. It’s not as though city folk have no way to enjoy the countryside. Other than from activists who want something for nothing and have their eyes on what’s left of the rural idyll in England, who is clamouring for farmers to be dispossessed of their property? Are there not public footpaths, greenlanes and plenty of byways to enjoy? If city people cared so much about the countryside, why, they could go around picking up all the rubbish that visitors leave behind, take note of all the things farmers are doing wrong te remedy the matter and take it up with their elected representatives. Perhaps these city folk concerned about the countryside could take note of the state of their country first, and make their elected representatives do their majority’s bidding, preferably without riding roughshod over well-earned property rights. The farmers have been getting CAP subsidies. Most of that goes to the big landowners. And then, it’s not as if nobody else gets subsidies and support. Governments, like the dictatorship in Brussels, has ever been in the business of buying electoral support. This has only got worse since the EC turned into the EU.

Anyway, what will be will be, but someday the farmers in the UK will be sorely missed by city people.

I live in a semi rural village and take a walk through the countryside every day. I can see no relationship between the issues described here and the countryside and people that I see daily. The biggest threat to our local countryside is the housing quotas imposed on Kent to accommodate Londoners.