Britain has entered the World Trade Organisation system as an independent player. One of the next big things on the WTO’s agenda is to decide on the rules that will govern digital trade. In the first of a series of posts, Steve Woolcock (LSE) discusses the state of the plurilateral negotiations taking place between 86 WTO Members including the US, the EU, and China on the future of the international trading system.

The growth of digital trade can be seen as the latest phase of globalisation. In the period after the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1948 it was trade in goods that raised questions about the balance between open markets and regulatory sovereignty. In the period after 1979, it was foreign direct investment. In the 2020s it will be digital trade. Digital trade is growing from an estimated US$ 150 bn in 1999 to US$ 26 tn in 2019 and growing at 8% a year. In 2019 digital trade was put at an estimated 6 per cent and rising of global exports. The COVID pandemic has accelerated the trend with on-line sales increasing further from the 17 per cent of global retail they were in 2020. This growth in digital trade raises questions about the sufficiency and suitability of existing trade rules, such as the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) that was negotiated in the 1990s, before the advent of the internet. But the current effort to define ambitious but inclusive rules for digital trade comes at a time when the international trading system in the shape of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is going through its most troubled period since 1948. Strategic competition – essentially concerning China – and the political and security implications of the use of data are also a significant complicating factor.

This growth in digital trade also has implications for political economy on the balance of costs and benefits of engaging in international trade. Physical goods that used to cross borders and be subject to tariffs are increasingly digitalised, which benefits human capital-rich economies but reduces tariff revenue for developing countries. The provision of services that once required a physical presence in a market, such as banking or business services, are increasingly digitally enabled. As a result, the broad balance of benefits between countries incorporated in the schedules of commitments to open trade in services in the GATS is in danger of being undermined. Digitalisation and the growth of digital platforms such as Google, Facebook and Amazon also have distributive effects within national economies as they gain at the expense of established, conventional suppliers. For example, Amazon’s growth at the expenses of high street retailers.

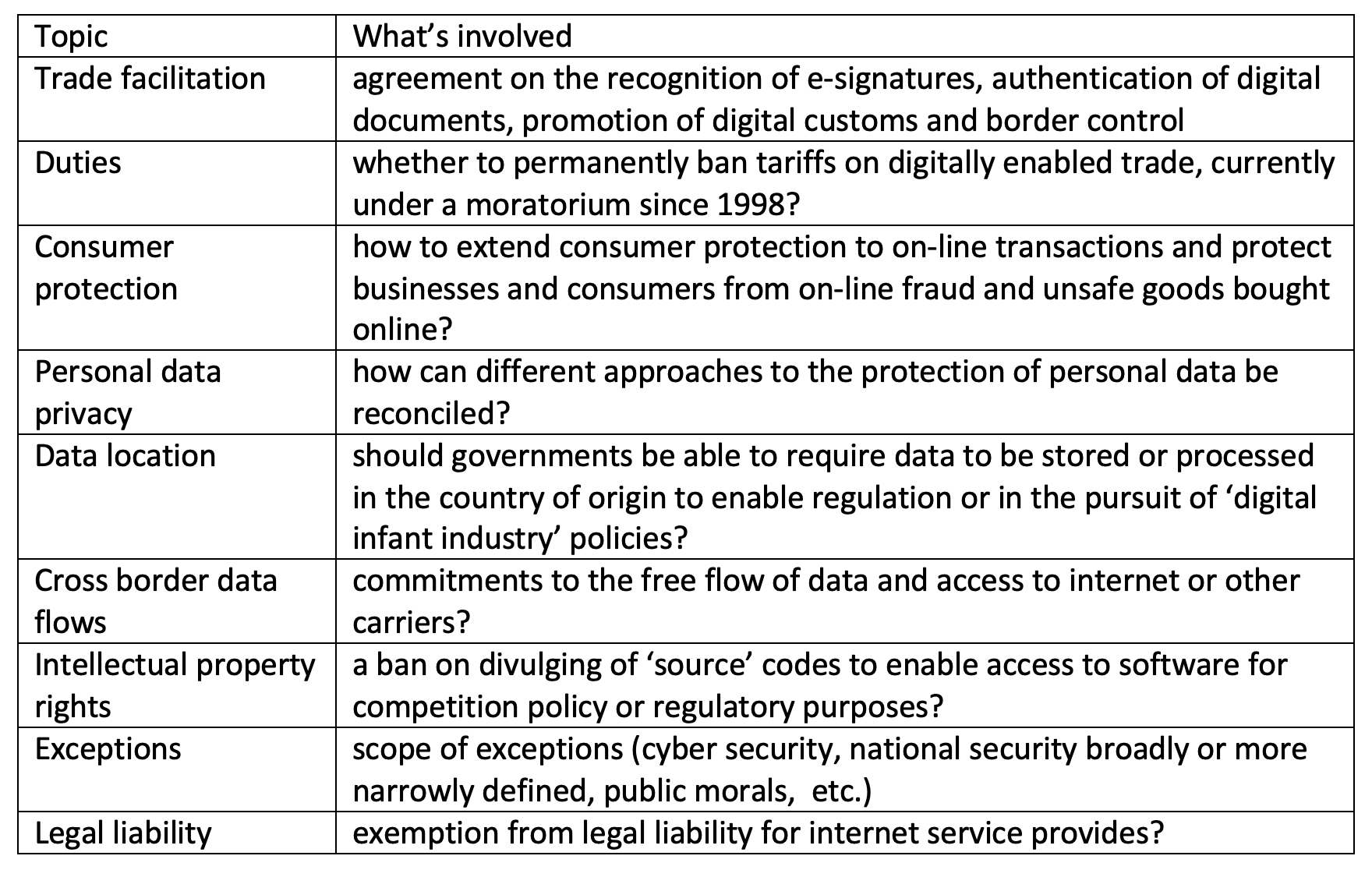

Whilst there have been discussions on e-commerce in the WTO since 1998, the current e-commerce negotiations started with a ‘Joint Statement Initiative’ (JSI) in 2017 supported by a group of 71 WTO members that has subsequently expanded to 86. The agenda includes the very practical means of facilitating digital trade such as recognising e-signatures as equivalent to ‘signed documents’ or efforts to streamline border controls by introducing digital trade documentation. It also covers consumer protection online, anti-fraud and anti-spam provisions and the much more sensitive question of personal data protection. As in any ‘trade’ agreement market access is on the table in the form of free cross border data flows, fair access to networks including those operated by the digital platforms. However, when dealing with access to digital markets, the state is concerned about the political and security implications of wide access to the endless flow of data and information. The challenge, therefore, is to balance domestic concerns with data privacy, cybersecurity and market access. Some parties to the negotiations also wish to protect certain commercially strategic activities from international competition. The table lists the main topics raised by the series of position papers submitted to the WTO.

With the stagnation of multilateral negotiations on trade in the so-called Doha Development Agenda (DDA), the question is whether progress can be made in digital trade with fewer than the total 164 WTO members involved, albeit when these account for 90 per cent of world trade? This format of ‘likeminded’ countries negotiating is termed a plurilateral negotiation. It is favoured by those WTO members that wish to press ahead with the negotiation of ‘high standard’ rules for digital trade. The difficulty of course is that there are different views on what these standards should be. In very broad terms these different approaches can be characterised as follows: the USA approach could be said to be industry-led liberalisation with US origin companies having a first-mover advantage in much of the digital sector. The EU is pursuing a more state-and-market led approach in that it sees the creation of a Digital Single Market in the EU as the best means of achieving the right balance between liberalisation and regulation. China, the third of the so-called ‘three digital realms’ is pursuing a much more state-led approach. Many developing countries remain uncertain of the costs and benefits of digital trade rules and are concerned about finding themselves on the other side of a permanent digital divide in the world economy.

Although the USA, EU and China, as well as a number of other OECD and developing countries, are involved in the JSI negotiations, India and South Africa have come out against such a plurilateral approach on the grounds that it undermines multilateralism. These two countries, along with other developing economies are concerned that the rules for such a vital and growing area of the economy should not be shaped by the more developed economies as they would argue was the case for goods and services. The challenge, therefore, is to find a balance between the desire for a rigorous set of ‘high standard’ rules that will provide the predictability needed for digital trade to grow on the one hand and the need to be inclusive of economies at different levels of development on the other?

If a way forward cannot be found at a multilateral level the expectation must be that preferential agreements will be seen as the best alternative, as has been the case in other areas of trade and investment over the past 20 years. In this respect the three ‘realms’ approximated by the divergent approaches to the topic centred around the US, EU and China will be important. The US has already established a relatively high standard agreement in the renegotiated North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA) now entitled US-Mexico-Canada (USMCA). The US has also had a major role in shaping the Comprehensive and Progressive Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP). The Trump Administration withdrew from this, but the e-commerce chapter remains that negotiated with the US included. The EU preferential trade agreements have yet to include extensive, comprehensive provisions on digital trade, due to the desire to define common EU standards first. China’s much more limited approach to commitments on digital trade are arguably compatible with the e-commerce chapter in the Regional Comprehensive Partnership Agreement (RCEP). This was recently adopted, but only after India opted out, in part due to the provisions on e-commerce.

The JSI along with other plurilateral agreements are on the trade agenda leading up to the next WTO Ministerial Conference scheduled for later this year. Progress on all the issues above is very unlikely, but keeping the show on the road will be important for the future of the international trading system.

This blog post introduces a series on digital trade that emanates from an extended and detailed simulation of the current WTO negotiations on e-commerce by LSE Masters students in the International Relations Department. This is the first of a series of posts informed by these discussions.

This post represents the views of the author(s) and not those of the Brexit blog, nor of the LSE.

[1] Digital trade here means trade in physical goods via the internet, as well as trade in digitally-enabled goods and services (i.e. goods and services in a digital form).