It’s no secret that gender equality is smart economics. If women played the same role in labour markets as men, as much as US$28 trillion could be added to global annual GDP by 2025. Worldwide, women own or operate 25 to 33 percent of businesses, and they grow faster than those owned by men. It should be obvious that when governments cultivate a business environment that benefits women entrepreneurs and workers, economic productivity is enhanced and development outcomes improve. Unfortunately, social discrimination, lack of incentives, and traditional gender roles only compound the difficulties women already face in entering the workforce.

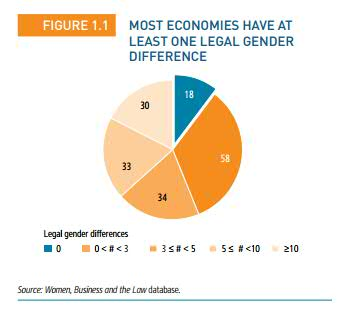

Rather than business regulations, it is often discriminatory provisions in family codes, labour codes, constitutions, property laws, and domestic violence laws that suppress women’s labour force participation. The World Bank Group’s Women, Business and the Law project studied these sources and found that laws restricting economic opportunity for women are still widespread. The fourth report in the series, Women, Business and the Law 2016: Getting to Equal, finds nearly 950 instances of legal gender differences across 173 countries. This includes countries where women are unable to sign contracts, are restricted from holding certain jobs, or are not protected from domestic violence or sexual harassment. In fact, 90 percent of the countries covered in the report have at least one law impeding women’s economic participation.

Consider a woman with a business idea. For starters, she must be legally eligible to work, fund the business, and sign paperwork in her own name. This is not the case in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, where married women are considered legal minors. There, husbands can prevent their wives from working, registering a business, and choosing where to live. In 127 countries, there are no legal provisions that prohibit discrimination by creditors based on gender. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates that there is an approximately $300 billion credit gap for female-owned small and medium enterprises. Differences in asset ownership between men and women could explain the gender gap in access to credit.

Consider a woman with a business idea. For starters, she must be legally eligible to work, fund the business, and sign paperwork in her own name. This is not the case in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, where married women are considered legal minors. There, husbands can prevent their wives from working, registering a business, and choosing where to live. In 127 countries, there are no legal provisions that prohibit discrimination by creditors based on gender. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates that there is an approximately $300 billion credit gap for female-owned small and medium enterprises. Differences in asset ownership between men and women could explain the gender gap in access to credit.

Furthermore, a country’s property regime can significantly impact a woman’s financial security and bargaining power within the household. Equal access to property directly impacts a woman’s financial security. Take Fatima: when a rocket hit her apartment in Gaza City and killed her husband, she was unable to lay claim to the home since her name was not on the title, leaving her financially vulnerable. Because most banks in developing countries require evidence of real property ownership as collateral for loans, women often lack the ability to borrow money for starting a business or entering the workforce. Only 18% of women in countries where husbands control marital property have an account at a financial institution, as opposed to 57% in countries where spouses jointly control property. This suggests that the gender gap prevents women from using property as collateral for loans.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2014, the gender gap in economic participation and opportunity is 60 percent worldwide. Wage gaps can be exacerbated where occupational segregation confines women to lower-paying sectors and activities. In Russia, women are prohibited from working in 456 specific tasks and occupations. Professor Elena Mezentseva at the Higher School of Economics makes the case that many of the restrictions are not protective but purely discriminatory, and were introduced to keep women out of high-paying professions. For example, women are prohibited from working in the lucrative nuclear industry despite experts’ belief that it poses no more threat to their health than men’s. When women are confined to certain jobs, entire industries lose half of their potential workforce.

Without legal protection from gender-based violence, women’s economic empowerment is further undermined. In the United States alone, eight million days of paid work are lost each year to domestic violence, costing approximately $8.3 billion in annual expenses. Violence against women undermines economic empowerment by preventing employment and blocking access to important financial resources. Laws that cover several types of domestic violence, including physical, sexual, emotional, and economic violence, can provide women with the protection necessary to enter the workforce and control their own assets. Among the countries covered by Women, Business and the Law, 46 do not have laws addressing domestic violence, despite the prevalence of regional conventions on the subject.

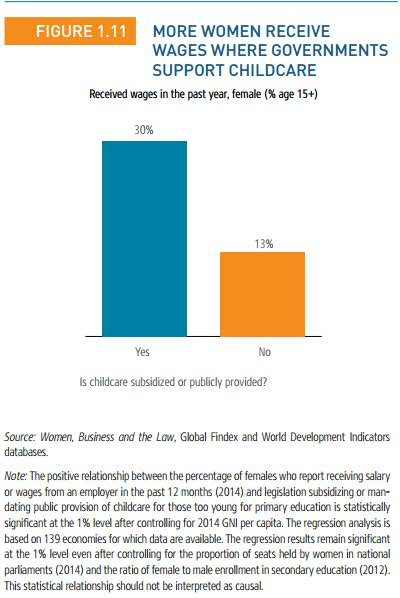

Enhanced gender equality can also be achieved through the provision of incentives that facilitate labour force participation. Studies indicate that some of the main barriers to women’s economic inclusion are the lack of childcare and the inability to balance both work and household responsibilities. For instance, over 44,000 children in Japan are on waiting lists to join daycare centres. Government-supported childcare and primary education can create opportunities for women to seek paid work or continue working after childbirth. Indeed, the percentage of women in formal employment in countries that provide public childcare is more than double that in countries that do not. Our report reveals that 39 countries have no form of public or subsidised childcare. This affects whether a mother decides to work outside the home or stay home with her children.

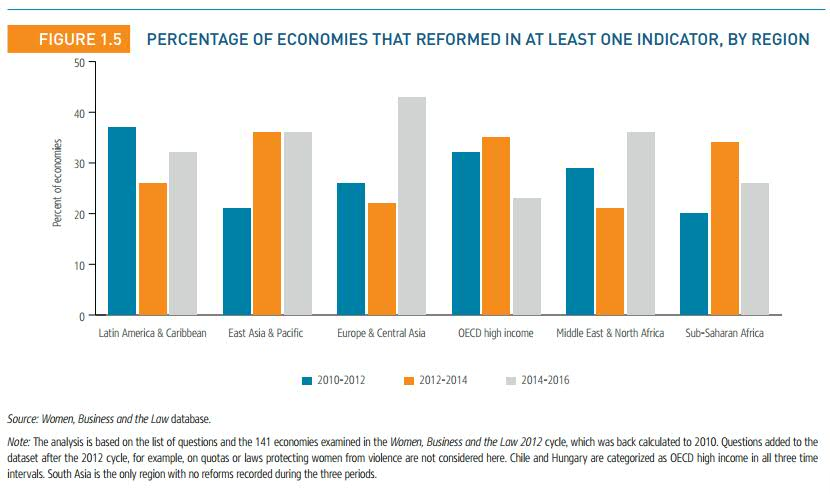

Wisely, governments are taking note of the impact their policies have on women’s economic participation. Women, Business and the Law 2016 measured 94 reforms in 65 countries that increased women’s opportunity. Belarus reduced the number of professions in which female work is prohibited from 252 to 182. Another 23 countries updated or introduced legislation relating to domestic violence, sexual harassment, marital rape, or child marriage. Nicaragua amended its family code to give married men and women equal property rights in choosing the marital home. Reforms like these can have far-reaching consequences, and I believe they will be associated with real economic outcomes.

As countries move toward greater gender parity, development and economic outcomes should advance exponentially. Improving women’s economic opportunities will allow countries to experience economic growth at their full potential, benefitting not only women, but their families and communities.

Featured image credit: Bold Content CC-BY-2.0

Nisha Arekapudi joined the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law in 2014, and primarily researches and analyses women’s opportunities for the Providing Incentives to Work and Going to Court indicators. She is a member of the New York State Bar and holds a JD/MA from American University’s Washington College of Law and School of International Service.

Great article Nisha! Very well captured the inefficiency as a result of not maximizing the women’s role in the work place. I knew we had domestic violence issues, but $8.3 B worth opens your eyes.

Happy to see you get published. Great job.

Best Wishes,

Tony

Very nicely done Nisha. US press focuses on domestic violence etc but misses out on the broader women rights issues around the world. You have highlighted those very well here.

Good luck and keep up this good work.

Subbu

If a woman cannot even exist legally on her own as an individual just to sign documents, this is denying a person of basic human rights. The woman cannot progress in life in such a way and will be forced into a partnership-“marriage” in order to survive.

What an eye opening article Nisha! Well done! It is unbelievable that even in our own country there are innumerable barriers to women progressing in the workforce. Some issues are cultural and some institutional. Domestic violence is a scourge even in “civilized” cultures The way forward has to include empowering young girls early in school to look up to role models in business and industry and support them through this journey. Only then will the developing world have a societal model to follow.