Spain has seen a huge influx of women into the workplace, but men and women’s experiences of work remain very different. Claudia Hupkau and Jenifer Ruiz-Valenzuela say there is scope for new family-friendly policies to help close labour market gender gaps and boost fertility rates.

Over the past 25 years, Spain has undergone a striking convergence between women’s and men’s participation in the labour market. While in the early 1990s only 50 women were active in the labour market for every 100 men, this had risen to 88 active women for every 100 active males by 2019. The rapid incorporation of women into the workforce has meant that the participation rate of women in Spain has now overtaken that in the European Union overall.

But despite rapid convergence in participation rates, women are still behind men in other key job market dimensions. Figure 1 shows that by the end of the 2010 decade, women are more than 27 per cent more likely to be unemployed, 10 per cent more likely to hold temporary (fixed term) contracts and 2.4 times more likely to work part-time. Not only do women fare worse, but the gender gap in these measures has barely improved over the past 15 years. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, which hit male-dominated jobs (e.g., in construction) disproportionately hard, there were some years in which gender gaps narrowed. But once the economy picked up, the gender gaps in these indicators started rising once more.

Figure 1. Labour market outcomes for men and women in Spain – 2005-2019

Notes: Own calculations based on Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA). Seasonally adjusted series from Q1/2005-Q4/2019. Sample of all individuals within the working-age population (16-64 years). Participation rates are computed as the total active population (employed and unemployed) over the total working-age population. Unemployment rates are computed as the total number of unemployed over the total active population. Temporary contracts show the share of individuals with a temporary contract among all those in employment. Part-time employment rates show the share of individuals working part-time among those in employment. All variables are derived using cross-sectional weights.

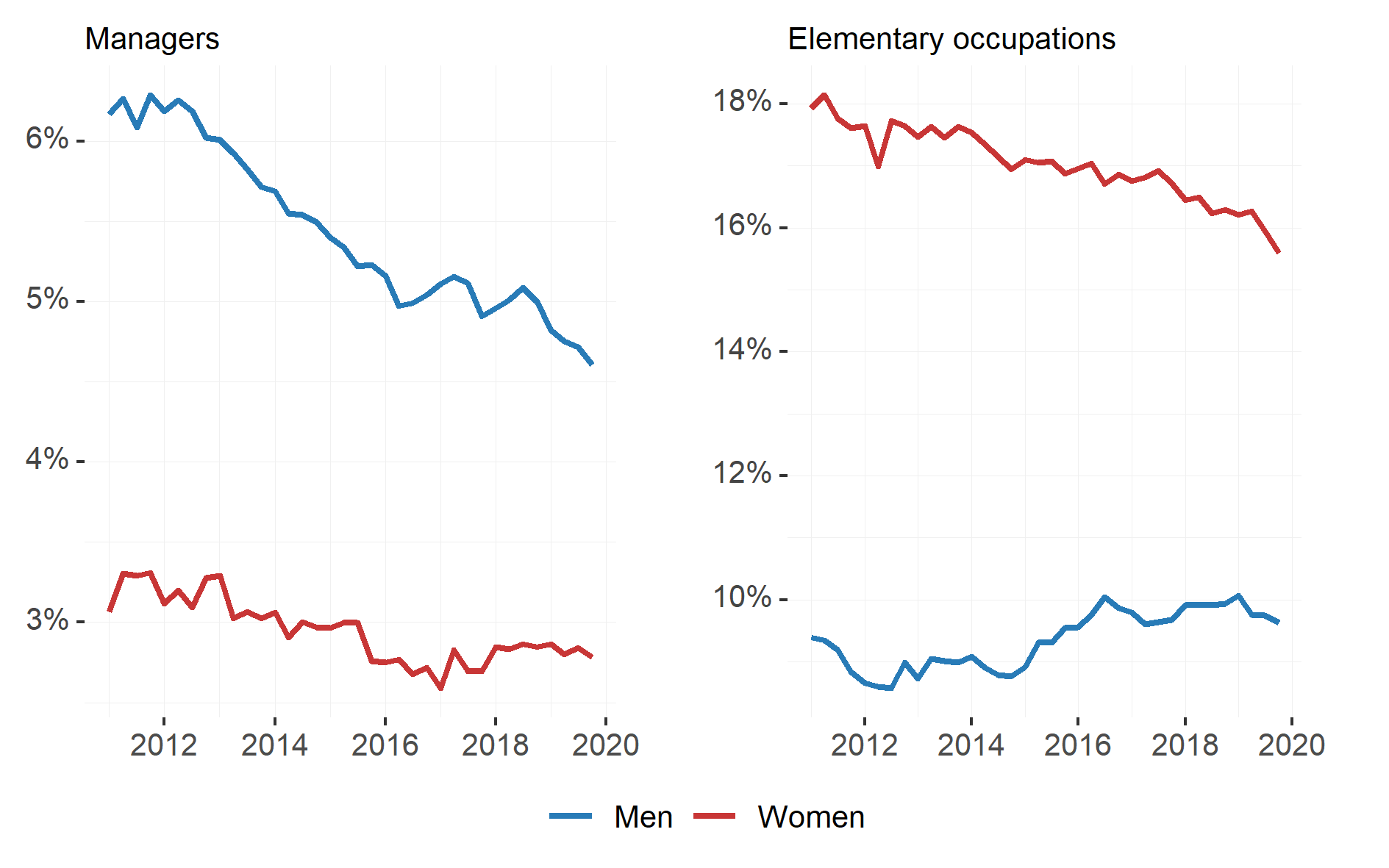

Figure 2. Percent employed in high-skill and low-skill occupations in Spain – 2011-2019

Notes: Own calculations based on Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA). Seasonally adjusted series from Q1/2011-Q4/2019. Variables show the share of individuals working in the specified occupation category over the total number of employed individuals by gender. All variables are derived using cross-sectional weights.

The gender gap is also surprisingly stubborn when it comes to the type of jobs women and men hold. As Figure 2 shows, women in Spain have not increased their presence in top-level occupations, like managers and directors, since 2011. At the same time, women continue to dominate employment in so-called elementary occupations, like cleaners, domestic workers, and food preparation workers. This is even though women in Spain have overtaken men in terms of tertiary education: in 2018, 50 per cent of women aged 25 to 34 held a university degree, compared with 38 per cent of men. Low-skill jobs not only pay worse than higher skilled jobs, but they also typically offer little career progression and room for growth.

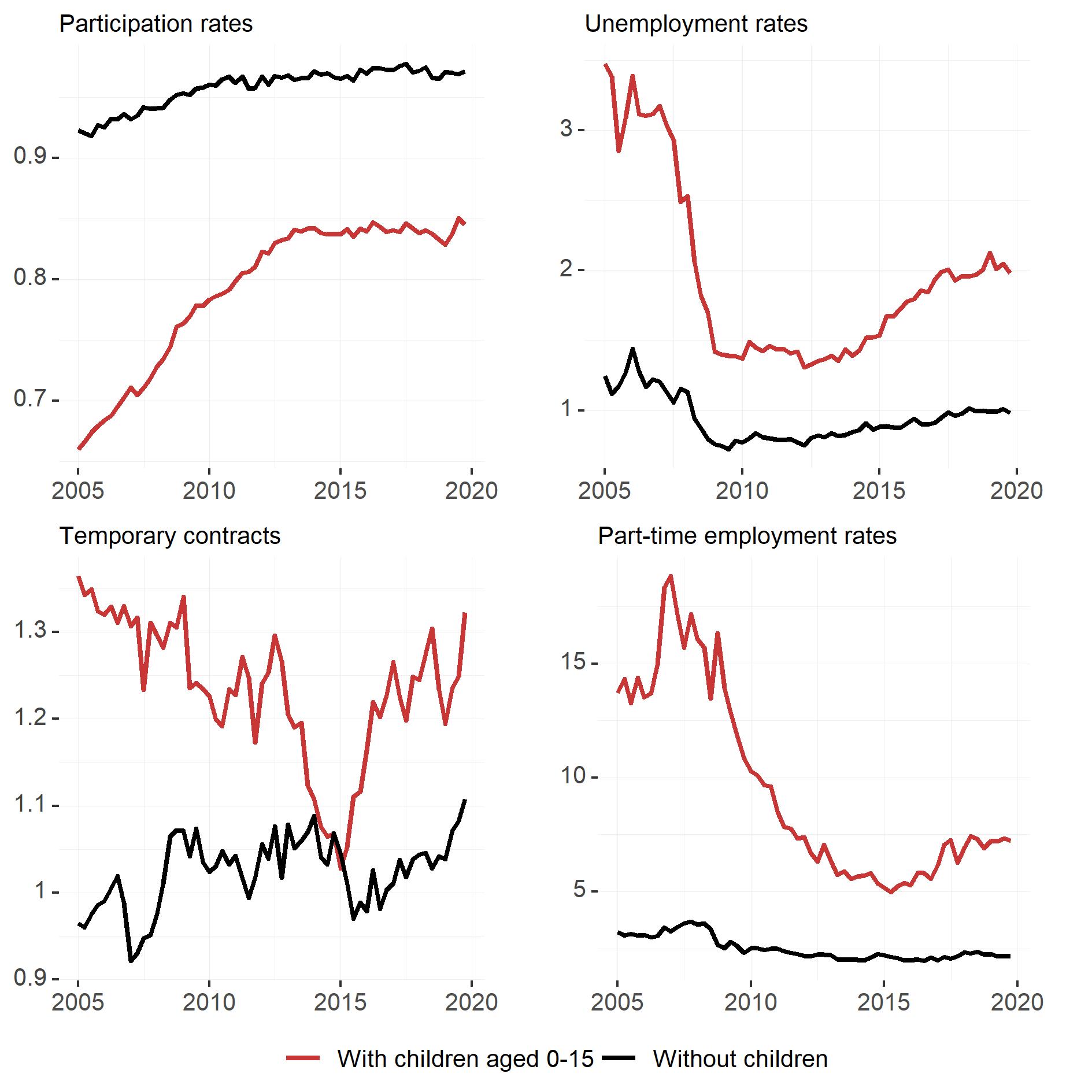

Inequality between men and women is further aggravated among people with children, irrespective of the indicator used. Figure 3 plots the ratio of female over male rates for different labour market indicators, for people with and without children. The Y–axis scale is informative of how many times more or less likely women are to be in a particular situation than men. Convergence in labour force participation rates has stagnated for women with children aged 15 and below over the last seven years. By the end of the 2010s decade, women with children aged zero to 15 are about 7.5 times more likely than men with children of the same age to work part-time, twice as likely to be unemployed and about 25% per cent more likely to hold a temporary contract. Overall, all these indicators show larger gender gaps for people with children than among those without children.

Recent evidence shows that the motherhood penalty might be driven by the fact that women chose jobs with family-friendly characteristics after the arrival of children, such as flexible hours (Goldin, 2014), being in the public sector or in lower-level occupations (Kleven et al, 2019). Thus, family-friendly policies, like flexible or shorter hours or long periods of parental leave might reinforce gender inequality if they are only taken up by women, by fomenting employer’s beliefs about women’s comparative advantage in childcare and reinforcing traditional gender roles (Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2016). Breaking up traditional gender roles thus seems crucial for enhancing equality in the labour market. Indeed, over a third of women with children under 5, and more than half of women with children aged five to 15 working part-time would like to work more hours. One in two women with very young children name childcare responsibilities as the main reason why they do not work more hours.

Figure 3. Women/men ratios of labour market outcomes in Spain by whether has children – 2005-2019

Notes: Own calculations based on Spanish Labour Force Survey (EPA). Seasonally adjusted series from Q1/2005-Q4/2019. Sample of individuals aged 25-54. Plotted series are computed as the ratio of the rate for men for the variable in question over the rate for women. See notes to Figure 1 for variable definitions. All variables are derived using cross-sectional weights.

A review of the literature on family policies suggests that there is scope for well-designed policies to help narrow gender inequalities in the labour market. Spain has recently implemented generous paternity leave entitlements for fathers. These have been shown to not only increase women’s employment, working hours, and earnings – but also to increase men’s involvement in childcare, meaning they have the potential to reduce gender gaps at work and in the home.

Policies that make it easier to combine family and work, such as financial incentives in the form of tax credits for working mothers and subsidised or free childcare for very young children, have also been shown to positively affect job market outcomes (Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2017). These latter policies would also help tackle a related issue: Spain is among the countries with the lowest fertility rates and the highest age of women at first birth. At the same time, Spain spends only about half of what the average country in the EU-27 spends on family and child benefits. Increased spending on such policies would thus likely reduce the motherhood penalty at the same time as raising fertility.

The welfare effect of such policies will depend on whether the gains in terms of tax revenues and economic output from increased female labour supply outweigh the cost of providing more affordable childcare or in-work benefits. Even if not all the increased expenditure on childcare provision or tax-credits is covered by the increases in income, social security, and payroll taxes generated from increased maternal employment, this does not necessarily mean that such policies would be inefficient. They may well bring other benefits, such as increases in fertility and, in the case of provision of free or affordable, high quality childcare, improvements in children’s educational outcomes in primary and secondary school.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on “Work and children in Spain: Challenges and opportunities for equality between men and women”, published on March 5th 2021 by Esade EcPol.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Standsome, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy