Communities in Australia’s mining heartland are in trouble and are calling on government to sustain them and rehabilitate closing mine sites. This month Alinta Energy will shut South Australia’s last two coal-fired power plants. Alinta has already closed its Leigh Creek mine and shackled government with responsibility for the purpose-built town that serviced the mine for over 30 years. But in the march of economic innovation, should these boom industries of yesteryear be allowed to draw from the public purse to postpone or cushion their collapse? The fossil fuel industry certainly thinks so, just as the ‘natural ice’ industry did over a century before them.

Today’s coal industry has learned all the wrong lessons from history and is mirroring the political strategy and slow death of the nineteenth century natural ice industry in America. They share the same business model, regional workforce, and spurious media spin. Most importantly, they both banked on aggressive political lobbying to lock out competitors to delay their own inevitable demise.

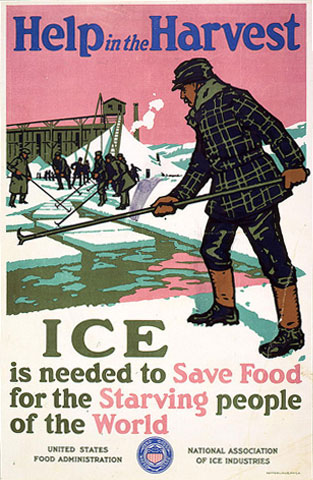

Beginning in 1806, enterprising Americans in frigid New England carved out ice blocks from frozen lakes and sold the blocks to consumers throughout the world, including as far away as Australia. The ice was used to preserve food and medicines, saving lives and introducing people to new culinary delights. The industry peaked at 90,000 workers in the U.S. before it petered out in the early 20th century as the marvel of artificial refrigeration swept the world. The refrigerated ice was cheaper, available year-round, and didn’t contain industrial contaminants that polluted the waterways that were harvested for ice.

The striking parallel to the coal industry (and the fossil fuel industry in general) is in how the natural ice industry dealt with competition during its decline. The decades-old pseudo-scientific front groups that the fossil fuel industry has nurtured to advocate that wind farms are unhealthy and coal is ‘good for humanity‘ are using a centuries-old playbook. Back in the 1870s the natural ice industry first combated claims that their product carried pathogens – a consequence of harvesting ice from polluted industrial waterways. The industry sued to have the findings of experts quashed. They later formed ‘The Natural Ice Association of America‘ to foster false scientific debate about the differences between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ ice. The strategy was not to put their new competitor out of business, but merely to kick their own job losses and industry collapse down the road.

Taxpayer support for the coal industry’s ongoing battle against cheaper and cleaner sources of energy is akin to supporting the original Luddites’ destruction of textile looms in 18th century England. The Luddites had no better chance of stopping the Industrial Revolution than the natural ice industry had of fighting artificial refrigeration, or the coal industry has of stopping the rise of renewable energy. Yet workers in these dying sectors largely found new jobs that innovation had created, and should be consoled by the fact that the wages, education and quality of life of their children and grandchildren far surpassed that which they endured and fought to retain.

When history kills an industry it’s a mercy killing. It’s an industry gone bad, or so far past its use-by date that it’s beginning to spread rot to once-healthy sectors. Consider the ‘medicinal’ leeches that actually spread blood-borne diseases, or the asbestos industry that insulated homes in exchange for cancer; or the pesticide DDT; or lead paint; or the surprise discovery this year that black lung, once considered a relic of history, might now affect 16 per cent of Australia’s coal miners.

This historical pattern is equally applicable to both blue- and white-collar professions. The same technological innovations currently creating ‘efficiencies’ in journalism, medicine and financial services may wipe out 40 percent of middle class jobs within 20 years. There are two schools of thought about what will happen next. The first school, populated with optimists and the historically-minded, argues this is merely the latest economy-wide shakeup. Some industries will shudder, highly-skilled workers willing to change jobs every few years will thrive, and economies will rebound. In short: ‘workers will be displaced, not replaced.’ Just last month another piece in the LSE Business Review advocated this position, citing the earlier unsubstantiated doomsday predictions of John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, and Thomas Mortimer.

The pessimists’ school argues that this time it’s different. Automation has previously helped the workforce and the broader economy by creating cheaper goods, greater demand, and increased job opportunities. But now the speed and breadth of automation across the economy leave nowhere new for displaced workers go. According to Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, the allegedly lacklustre economy since the turn of the twenty-first century can be partially blamed on automation’s ‘great decoupling’ of economic growth and increased job creation. In the words of Brynjolfsson, ‘It’s the great paradox of our era … Productivity is at record levels, innovation has never been faster, and yet at the same time, we have a falling median income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling behind because technology is advancing so fast and our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.’

Whichever path the next few decades take, strained taxpayers will almost certainly resist subsidising the now embattled companies that have used their wealth and influence to peddle false science, suppress competition, and contribute to climate change. Like the natural ice industry before it, future generations will likely remember coal for bringing greater quality of life and opportunities in its day. But history is less forgiving of industries that overstay their welcome and politicians who prop them up at the expense of economic growth, environmental sustainability and public health.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Ice Cutting on Lake Kragero, Norway, by

William Richardson (Public domain), via Wikimedia Commons

Brett Goodin recently completed a PhD in the School of History at the Australian National University. His research appears in the Australian Journal of Politics and History, the Huntington Library Quarterly, and Melbourne Historical Journal, and has been supported with fellowships from the International Center of Jefferson Studies at Monticello, the Huntington Library, the David Library of the American Revolution, the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Brett Goodin recently completed a PhD in the School of History at the Australian National University. His research appears in the Australian Journal of Politics and History, the Huntington Library Quarterly, and Melbourne Historical Journal, and has been supported with fellowships from the International Center of Jefferson Studies at Monticello, the Huntington Library, the David Library of the American Revolution, the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The article made an interesting study. More so the way, the threats likely to emanate from advancements in technology, automation and AI, which are bound to affect the working populations and dissipation of jobs. The changes being effected in our society have been brought very succinctly by the writer by comparing them to the changes that we have seen ourselves or read about . Things like bans on Asbestos, DDT etc. Complements to Brett for elaborating upon a nasty subject of job losses through some anecdotal evidences, which one can easily relate to.