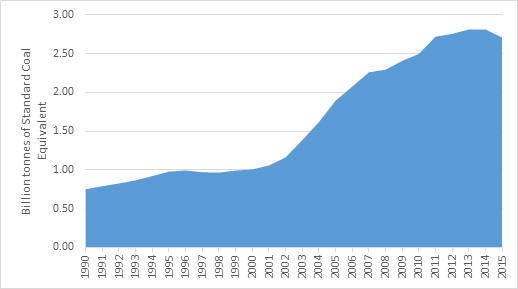

Something quite remarkable is happening in China. The country’s coal use grew at more than eight per cent per year between 2000 and 2013. But, in 2014, coal use barely grew at all and then it actually fell by more than three per cent in 2015.

Figure 1: Chinese coal consumption, 1990–2015

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics

This drop in coal consumption in China coincided with a 2.5 per cent drop in coal production and a 30 per cent drop in coal imports. The decline is good news for the world, as it means the country’s carbon dioxide emissions fell by up to two per cent in 2015. It is just possible that 2014 could turn out to have been the peak for China’s carbon dioxide emissions.

In a recent article, Lord Stern and I explain the causes of this remarkable turnaround. We also forecast the likely trajectory of China’s CO2 emissions from energy over the next decade.

Structural change in China

The drop in coal consumption can be attributed to two factors. First, shifts in the wider Chinese economy have constrained the growth in China’s energy demand. And, second, China’s energy supply is diversifying, away from coal.

Let’s deal with the demand side first.

After a long period of double-digit GDP growth (on average), China’s economic growth has been slowing gradually since 2011. The slowdown marks the start of a structural shift: away from an economic model dominated by extremely high rates of savings, capital investment, and production growth in low-value energy-intensive industries (such as steel and cement manufacturing); and towards an economic model focused more on growth in household consumption, services and high-tech manufacturing (which are less energy-intensive).

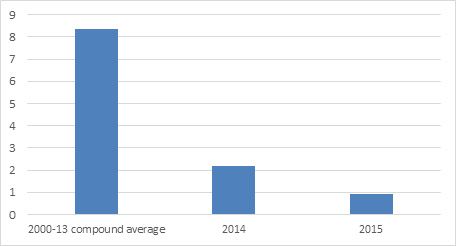

This structural shift in the composition of economic activity, along with policies to improve energy efficiency within industries, have caused China’s total energy consumption growth to slow dramatically in 2014 and 2015 (see Figure 2). Total primary energy consumption grew by 0.9% and electricity generation grew by a mere half a percent in 2015.

Figure 2: China Total Primary Energy Consumption Growth (% change per year)

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics

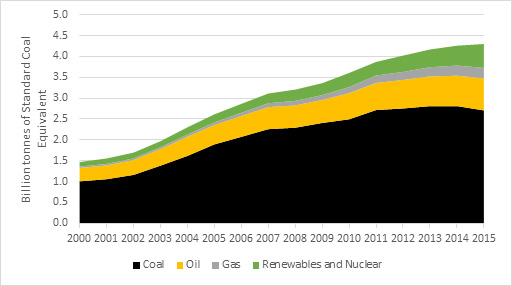

As for the supply side: China’s energy supply mix has continued to shift rapidly away from coal (both in electricity generation and in industry). Record levels of wind and solar capacity – as well as large amounts of hydroelectric, nuclear and gas-fired power capacity – were added to China’s electricity grid in 2015. The energy produced via these sources helped to reduce coal’s share in China’s Primary Energy Consumption (see Figure 3).

These supply-side trends are being driven by a combination of concerns about air pollution, energy security and climate change. China’s strategic vision is also playing a role as the country strives to be an innovative and globally competitive manufacturer in the rapidly growing global markets for clean energy.

Figure 3: Chinese Primary Energy Consumption by source

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics

Reaching peak-emissions

We forecast that China’s carbon dioxide emissions are likely to peak within the next decade (if they have not done so already). Emissions growth will likely be slow.

With high levels of excess capacity already blighting the steel, cement and coal industries, we expect the shift away from energy-intensive industries to continue to put downward pressure on energy consumption growth. And we expect China’s energy supply to continue to shift away from coal. Recently-released statistics for January and February 2016 suggest that each of these trends is in fact accelerating.

Both continued structural change in the wider economy and ongoing energy sector transformation feature strongly as themes of China’s recently-released 13th Five Year Plan (2016–2020). For example, China’s government has recently announced targets and funding mechanisms to close hundreds of millions of tonnes of excess coal and steel production capacity and to support the redeployment of millions of workers from these industries. It has also imposed a three-year moratorium on new coal mine approvals.

China’s carbon emissions trajectory in the next few years will depend largely on how quickly coal consumption declines relative to growth in oil and gas consumption. This will determine whether emissions grow moderately or continue to fall.

There are a number of risk factors that could cause emissions from fossil fuels to be higher than expected. These include political resistance to necessary reforms from industries and regions with high concentrations of coal mining and steel production, and faster than expected growth in oil demand in the transport sector.

Avoiding dangerous climate change

The new outlook for China’s carbon dioxide emissions is welcome news for the world. If the double digit rates of heavy industry-fuelled economic growth and unprecedented levels of coal use seen in China during the first decade of this century were to continue, it would make it very difficult for the world to restrain global temperature increases to below 2°C.

The more realistic emissions trajectory that we forecast (modest, if any, increase in emissions with a peak somewhere in the decade before 2025) would, in contrast, mean the world has a fighting chance to achieve that goal.

Attention must now turn to how countries, including China, can work domestically and cooperatively to introduce the policies necessary to ensure emissions peak as soon as possible and fall rapidly after they peak.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post appeared originally on LSE’s Grantham Research Institute blog, and is based on the author’s paper China’s changing economy: implications for its carbon dioxide emissions, co-authored with Nicholas Stern, in Climate Policy, 16 March 2016.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Coal barge in China, by Rob Loftis, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Fergus Green is a climate change policy consultant and researcher. He is currently undertaking a PhD in Political Science in the LSE’s Department of Government. From January 2014 to October 2015 he was a Policy Analyst and Research Advisor to Professor Nicholas Stern at the LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the ESRC Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy.

Fergus Green is a climate change policy consultant and researcher. He is currently undertaking a PhD in Political Science in the LSE’s Department of Government. From January 2014 to October 2015 he was a Policy Analyst and Research Advisor to Professor Nicholas Stern at the LSE’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the ESRC Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy.