Although England have performed well in Euro 2016 so far, the betting markets still put them some distance behind the favourites for the tournament, Spain, France and Germany. Why is there such a low probability of England winning Euro 2016? Of course there are many reasons but an important one has been downplayed so far: migration. Freedom of movement enhances team performance.

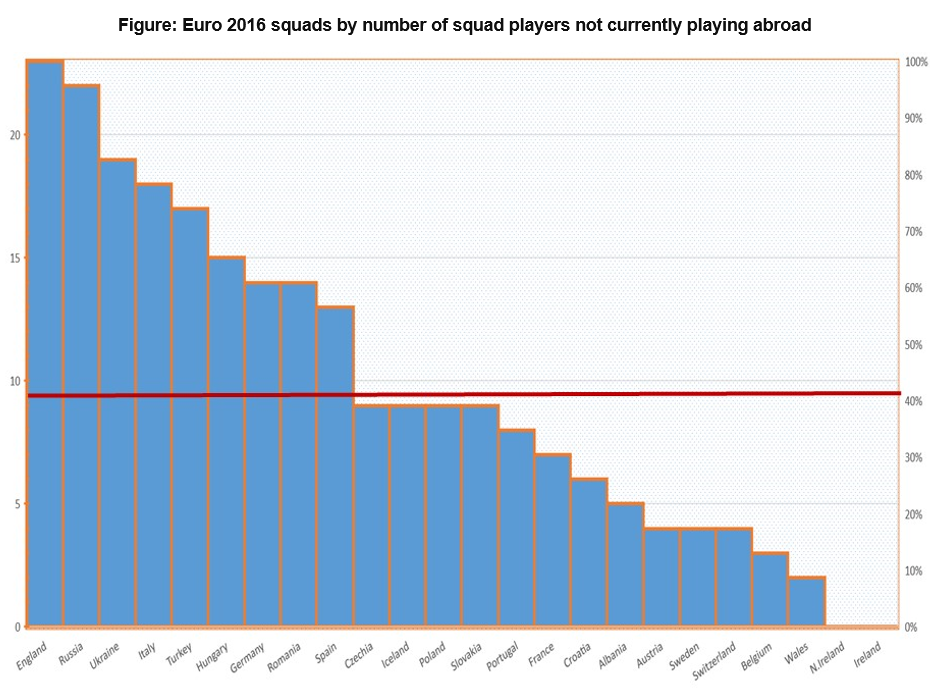

The English team is the only squad in the tournament that does not have a single individual playing abroad. In other words, England is the only team (out of 24) for which every single footballer currently plays for a domestic team. Each national squad has 23 players. England has all 23 playing at home, Russia comes second with 22, and Ukraine third (21). Italy comes fourth but it has two born and raised Brazilian players. Germany has 14 “home players”, Spain (13), Portugal (8) and France (7.) The average is about 10.

Source: Uefa

Why does diversity (which in this case is driven by migration) matter for performance? Like football, globalisation generates winners and losers. Globalisation winners tend to be those that “have done their homework”. Countries that developed domestic capabilities that can take full advantage of the mobility of capital, labour, goods and services are the likely winners. Mobility of labour has tangible as well as intangible benefits.

The tangible benefits of migration are significant and positive, albeit small. Typically, a 10 per cent increase in migration leads to a per capita income gain of about 2 per cent with most of it channelled through productivity (rather than investment or human capital). Another tangible benefit is that freedom of movement makes football more competitive: it reduces average goal difference between national teams. The share of national team players that play abroad has a positive impact on national team performance.

Why is migration good for football? Human capital spill-overs may be one reason. Players learn from other players. There is evidence showing that more linguistically diverse teams tend to do better in the Champions League. Another mechanism is that players are attracted to countries in which training facilities, equipment and nutrition are of higher quality.

The English football team and the intangible benefits of migration

If freedom of movement is so crucial for the performance of national teams, what explains England’s disappointing performances in recent tournaments? After all, the Premier League is a commercial and sporting success. It supplies a huge number of players to all major teams in Euro 2016.

An important reason may be that the most substantial benefits from migration are intangible. Migration may generate benefits for international football when it is deep, that is, when it involves two-way flows. Foreign players benefit from playing in England but the reverse is not true: few top English players play abroad. One may think that with so many foreign players in the Premier League, those in the English national team do not need to play abroad: they can learn from home. Most available evidence, at least since 1966 when England last won a major tournament, seems to be to the contrary.

One example of such intangible benefits is that migration may matter because it allows exposure to different refereeing norms, traditions and standards. Football rules are the same everywhere, but their interpretation and enforcement differ slightly (and at the top level, these small differences count). In England refereeing standards are unique: in England “football is a contact sport” and the “tackle” is king. If you ask English fans about which they think is the most memorable moment in an international football game many will mention Bobby Moore’s 1970 tackle on the greatest (by a mile) player ever as one of their top choices. Not a goal, a tackle.

Knowledge about how to play in different refereeing traditions is an important intangible benefit and may explain most of the benefits of freedom of movement to modern international football. When you have in your team players that have knowledge and experience of refereeing norms and practices of the four or five main European leagues, this becomes a very valuable repository of knowledge. This effect may be compounded in the European Championships because all referees officiate in Europe. This is a different case from that of the actually most important football tournament in the world where referees also come from Africa, Asia and the Americas.

This leads us finally to some lessons we can take from the beautiful game to the not-so-beautiful Brexit debate. It is clear the latter has been defined by two issues, migration and the economy. A large part of its poverty has been the inability to explain how these are not two independent and unrelated factors. Migration is good for (economic and sporting) performance. Yet the magnitude of these positive effects may depend both on context (the willingness, inclination and capability to enjoy potential benefits) and on our ability and willingness to measure, understand, and communicate clearly the relative importance of intangibles. Optimistically, we may still have everything to play for.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post appeared originally on LSE Europp.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Nauro Campos is Professor of Economics and Finance at Brunel University London. He is also affiliated with ETH Zurich and IZA-Bonn.

Nauro Campos is Professor of Economics and Finance at Brunel University London. He is also affiliated with ETH Zurich and IZA-Bonn.