Unions decry the inequality produced by zero hours contracts and call for an outright ban on them, while industry representatives say gig jobs boost employment. The truth may lie somewhere in the middle. Chris Coates reviews the literature on this issue and writes that a ban on zero hours contracts would be counterproductive. He lists some policy suggestions that have been made by researchers.

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) wants zero hours contracts banned, but the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) says they “play a vital role” in our current high employment levels. A paper in the British Medical Journal in January showed gig workers’ mental health was worse than that of people employed full- or part-time, but better than that of the unemployed, I thought an overview of research in this area could help us find some middle ground.

Helping people work?

Employment has been growing for over a decade, just as the gig economy has, but is there a causal link? To find out, research from the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) at the University of Essex asked:

- do jobs with unstable hours and pay help the unemployed move into work?

- do they benefit groups that typically face barriers to work – lone parents, mothers with small children, the low skilled, the less educated, and the long-term unemployed?

If so, we would expect people in areas with a greater number of unstable jobs to be unemployed for shorter periods. In fact, Labour Force Survey data showed the opposite: in areas with a larger share of unstable work, people stayed unemployed longer.

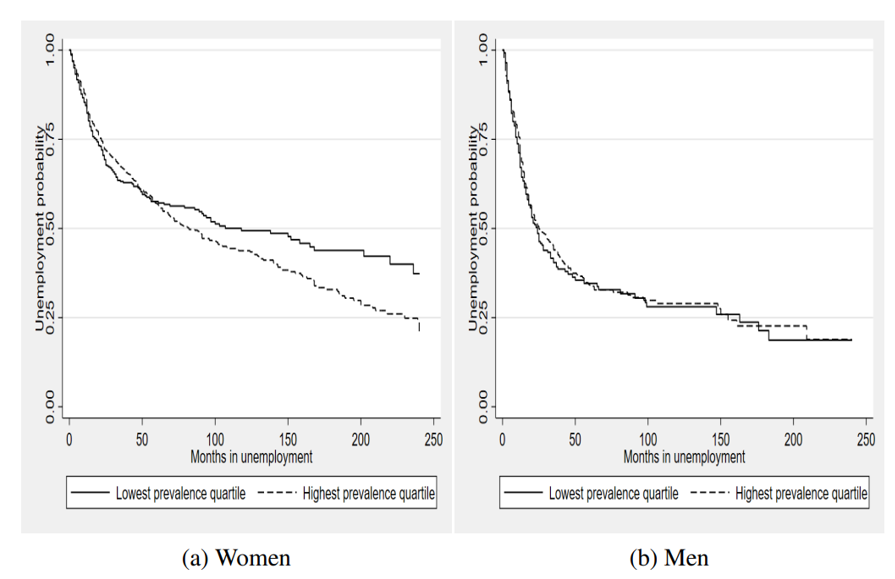

Data from Understanding Society (the UK Household Longitudinal Study) showed that women with lower levels of education in areas with a higher share of unstable jobs were more likely to leave unemployment only when they had been unemployed for five years or more. For shorter spells of unemployment, the differences were minimal. For low-educated men, “the two curves track each other very closely” – in other words: there was hardly any difference at all.

Figure 1. Probability of remaining unemployed by prevalence of jobs with variable hours/pay in the local labour market

So, perhaps the gig economy isn’t helping people into work – or at least, not on its own – but is it good for people in other ways?

Mental health

Research has found that “the mental health of zero-hours workers is, on average, 12.2% worse than other workers” and that income insecurity and job (dis)satisfaction are the important factors. The above-mentioned paper in January’s BMJ showed mixed results on mental health and life satisfaction, because gig workers are lonelier and their finances more precarious than other workers’, but they’re less financially precarious than the unemployed.

The quality of work

Another paper says that, compared to other workers, these employees are on average “younger, more female … in lower-status jobs, more private-sector focused, and have lower educational achievement”. While we might think of these jobs as being menial or low-skilled, though, about a fifth have managerial status – but crucially, “only 4% feel they have the duties of one … [which] suggests that zero-hours jobs are … associated with lower job control”.

We also know from research that people who move into low quality work have higher levels of chronic stress than those who stay unemployed. They may not be claiming unemployment benefits, then, but their work may have implications for their health – and that also costs the state money.

The question of choice

It’s been suggested that people with existing health conditions might choose zero-hours contracts because flexible work fits more easily around a challenging life. One of the mental health papers above, though, concludes that “the flexibility offered … is restricted and of a specific scope”, and quotes a TUC survey which says “43% of zero-hours staff say they are on a [zero-hours contract] because it is their only option”. An experiment at ISER two years ago concluded that uncertainty “is a burden for workers”.

Is this a problem?

With all this in mind, though, can we say that the gig economy is a social ill? Torsten Bell at the Resolution Foundation says instability is not the problem we might think. “Firms are much less likely to fire these days. In the late 1990s, 0.8% of workers would lose their jobs each quarter; immediately pre-pandemic that had halved.”

Also, while the Labour Force Survey saw a rise of 132% in the prevalence of zero-hours contracts between 2012 and 2013, the House of Commons Library has offered an explanation. This “very likely reflected better awareness of zero-hours contracts as a result of extensive media coverage in 2013”, because around half of the reported change came from people who said they had been in their job for over a year. “Some respondents must have failed to report or identify that they were on a zero-hours contract in previous surveys.”

Potential policy approaches

As long as there are those – students and semi-retirees, for example – who want this kind of work, a ban on zero hours contracts would be counterproductive, but some researchers have made policy suggestions. Thomas Keely at Aberdeen is in favour of more secure work for those who want it, and more schedule control, “allowing greater flexibility to those who need it and greater security to others”.

Silvia Avram at ISER suggests: “Employers could be mandated to offer workers a contract that reflects their regular working hours rather than a minimum. Limits on short-term scheduling and re-scheduling, as well as compensation for shifts cancelled at short notice, would similarly help … [and] the welfare system can support workers in unstable jobs by promptly topping up their pay when work is unavailable.”

And changes have been made. In 2015, for example, new regulations made exclusivity clauses unenforceable. These had prevented people from seeking extra work with another employer if they weren’t getting enough hours or salary from the one they were contracted to.

It’s possible, then, to introduce or amend legislation to encourage greater cooperation and balance between employers and employees – and the evidence suggests there are further adjustments we could make to improve life for people on low incomes and in precarious work.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Paul Hanaoka on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.