How do individuals behave when they have to compete against their former employer and colleagues? As the rate of employee mobility is steadily increasing over the last decades an impressive body of research has studied the performance implications of employee mobility. Most studies conclude that hiring individuals from rivals is beneficial for the performance of the hiring firm. The idea is that individuals transfer their human capital, that is, their knowledge, skills, talent, and know-how and their social capital, that is, their connections to clients, suppliers and experts, to the new firm. This transfer has been shown, among others, to be positive for developing innovations, entering new product markets and increasing market share and thereby boosting firm performance. In a nutshell, prior literature has primarily considered employee mobility between competitors as a transfer of resources with a focus on what individuals can do.

However, my colleagues Pascal Kober and Leon Zucchini and I argue in our paper that to fully understand the implications of employee mobility, that is, what an individual will do at a new organisation, it is necessary to consider both what an individual can do and is willing to do. What individuals are willing to do depends on how they feel about the new and the former organisation and colleagues, especially when competing against them.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that competing against a former employer and colleagues makes individuals feel uncomfortable. For example, Wayne Gretzky, the greatest ice hockey player ever, once said after his trade from the Edmonton Oilers to the LA Kings: “I hated coming back to Edmonton to play. I say that in the best possible way. […] It was really hard. I never liked it. I never really felt comfortable. I always felt so much a part of the team and so much a part of the city. I dreaded it.” In a similar vein, John Thain, a former co-president at Goldman Sachs, noted after his move to become chairman and chief executive at Merrill Lynch: “I love Goldman Sachs and I love the people, but I think Merrill will be a great competitor”.

Building on this anecdotal evidence we argue that individuals experience a conflict when they compete against their former employer. The conflict arises because individuals simultaneously identify with both organisations although they are supposed to only identify with the new one. To reduce the conflict, individuals strengthen their identification with the new organisation and de-identify with the former by competing harder against it. This increased effort helps the new organisation to outperform the former which in turn makes the new firm more attractive for the employee. We further argue that the extra effort is targeted towards non-former colleagues of the rival organisation. In contrast, as moving employees still identify with their former colleagues and as this identification is not problematic for the new firm or the new colleagues individuals behave less competitively towards former colleagues.

We address our research question using a dataset of professional ice hockey players in the North American National Hockey League. The data comprises information on all the former and present employers and colleagues of each player, and all events that occurred on the ice in the 2011/12 season. In line with our predictions, we find that individuals exhibit more competitive behaviour towards a former organisation than towards a non-former organisation. By contrast, individuals exhibit less competitive behaviour towards former colleagues than towards non-former colleagues.

While we find strong empirical support for our predictions we further wanted to see whether individuals’ behaviour towards former organisations may also depend on the circumstances in which they parted. For example, employees who were fired might harbour a grudge against their former employer. To ensure that neither anger nor revenge sparked the increased competitive behaviour we observe, we identified the reason why each player left the team. A players’ move to other teams is usually either player-initiated, team-initiated, or due to a lay-off. Layoffs are clearly associated with negative feelings by the player. In line with this idea, we find that players who were laid off are extra-competitive against their former team. However, the differences between the coefficients for the different reasons to leave the organisation are not statistically significant.

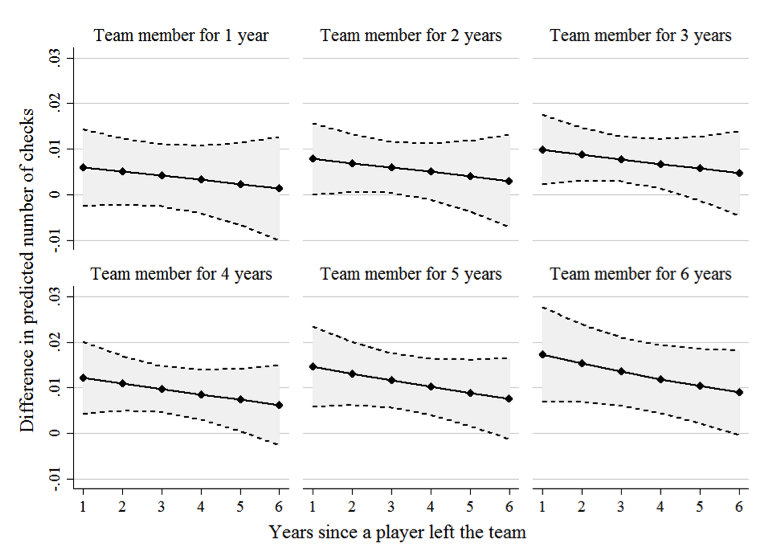

Finally, we analyse if and how movers’ competitive behaviour changes over time. We find that the positive influence of playing against the former team on competitive behaviour increases with an individual’s tenure at a team but decreases with the time elapsed.

Figure 1. Competitive behaviour over time

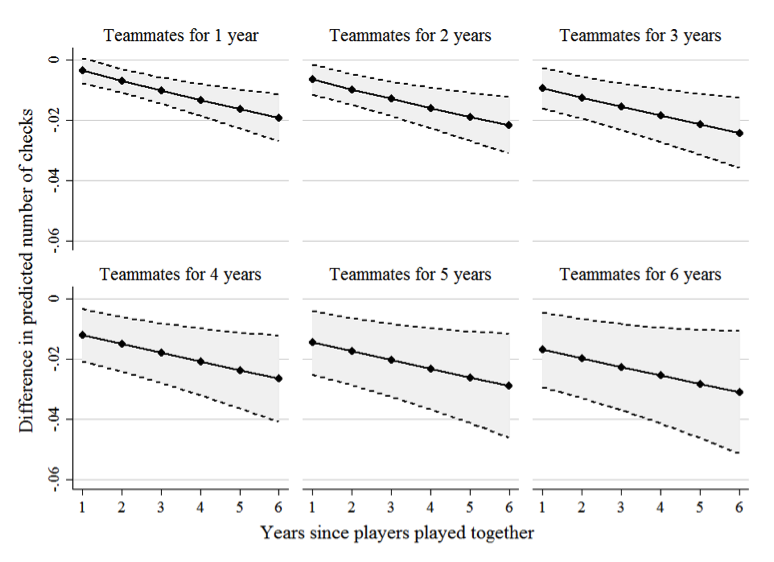

At the colleague level, the length of time two players were teammates reduces a player’s competitive behaviour and players showed less competitive behaviour the longer ago they were teammates.

Figure 2. Competitive behaviour over time – college level

Our findings have several implications for managerial practice. First, our results suggest that when firms hire employees from competitors, they not only gain human and social capital but can also expect the new employees to work particularly hard when competing against their former employers. In contrast, employees are more considerate when competing against former colleagues. When hiring from competitors, organisations might therefore find it attractive to hire entire teams. In such cases, the newly hired team is likely to behave more competitively towards the former organisation as their closest colleagues from the former organisation have moved with them. Second, our study indicates that firms can soften competition by facilitating networking between employees. Softening competition can be beneficial for the hiring and the losing firm to increase their profits. When there is frequent movement of staff between competitors, for example in Silicon Valley, individuals are likely to compete against former employees. Our results suggest that networking between current employees softens their competitive behaviour when hired by competitors. The more ex-colleagues employees have, the more likely they are to reduce their competitive behaviour.

Third, our research offers another reason why firms might benefit from having non-compete clauses in their contracts. These can not only help firms to prevent the loss of good employees to rivals but also prevent facing a highly motivated individual working for a rival. Non-compete clauses allow the individual to have some time before competing against the former organisation. The individual can use this time to properly de-identify with the organisation. This will benefit the former employer because the individual will behave less competitively when facing them in future.

Watch a short video abstract of the paper:

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post is based on the paper Coming Back to Edmonton: Competing with Former Employers and Colleagues, Academy of Management Journal, April 1, 2016.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Opening face-off, by mark6mauno, CC-BY-SA-2.0

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Thorsten Grohsjean (t.grohsjean@lmu.de) is an assistant professor for strategy and organization at Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich. Before joining LMU he was a research associate in the Innovation & Entrepreneurship Group at Imperial College London. His research interests include macro-level questions of organizational learning and innovation, as well as micro-level questions on the development and portability of human and social capital across organizations.

Thorsten Grohsjean (t.grohsjean@lmu.de) is an assistant professor for strategy and organization at Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich. Before joining LMU he was a research associate in the Innovation & Entrepreneurship Group at Imperial College London. His research interests include macro-level questions of organizational learning and innovation, as well as micro-level questions on the development and portability of human and social capital across organizations.