Athens street scene, by Luigi Guarino, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

Athens street scene, by Luigi Guarino, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

The “added worker effect” hypothesis suggests that the wives of unemployed husbands increase their job-finding efforts in order to maintain the family’s standard of living (Gruber and Cullen, 2000; Stephens, 2002). We investigate this hypothesis in the Greek labour market, which is characterized by increased job separation rates (layoffs, contract termination, resignations and retirement), substantial employment exits (movements from employment to unemployment or inactivity) of male spouses and persistently low job-finding rates (Daouli et. al. 2015). Our findings suggest that wives whose spouses lost their jobs during the crisis have indeed increased their labour force participation rates, i.e., they have entered the labour market, but this increase has not led to an analogous increase in employment. Thus, the population of families with jobless spouses has increased substantially with profound detrimental effects on their standard of living.

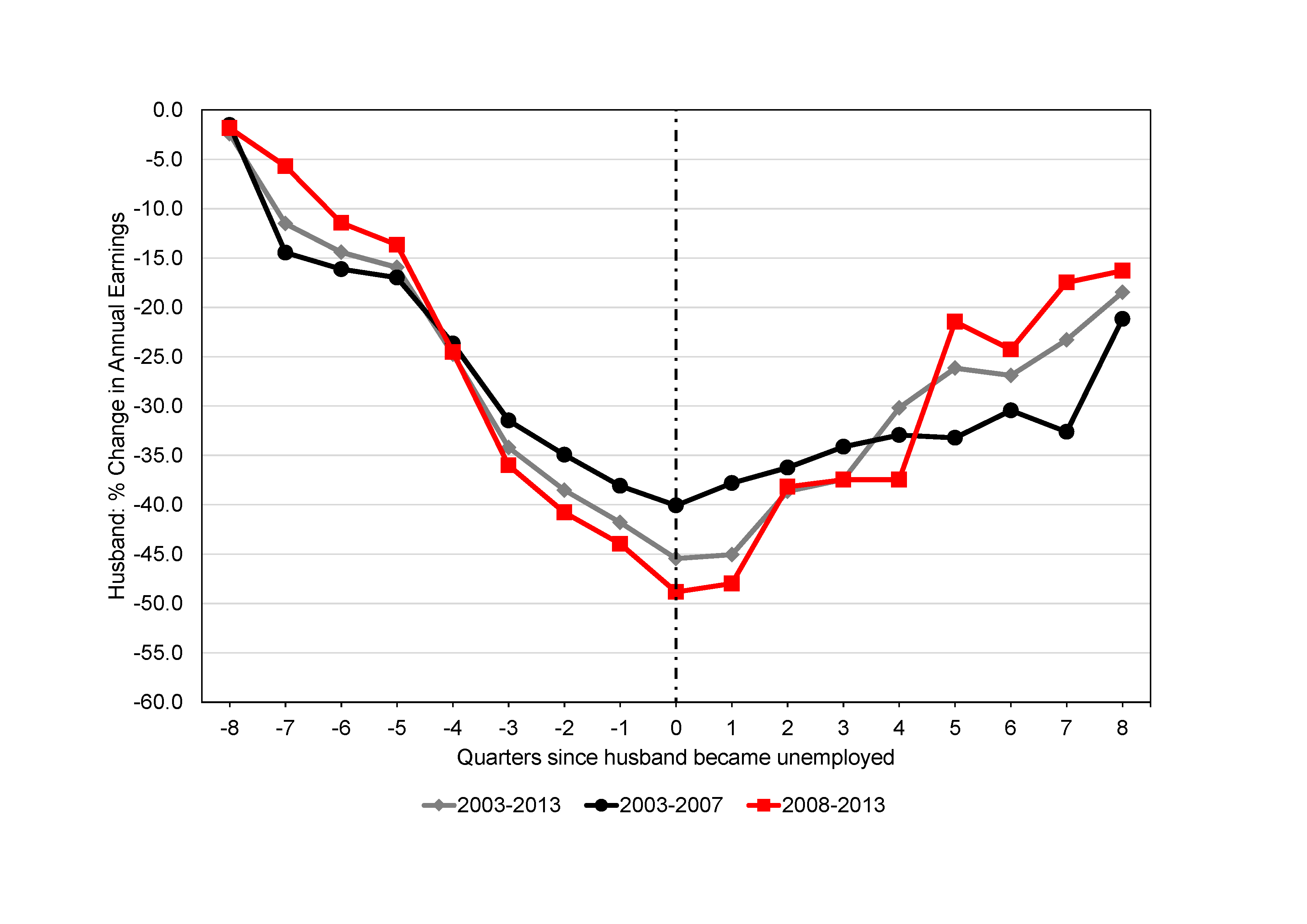

Using a representative dataset with information on monthly employment histories of spouses in Greece (EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, EU-SILC) for the period 2003-2014, we detected (Figure 1) that husbands’ earnings losses due to employment exit are higher than those losses of husbands who were continuously employed, especially in the crisis period (2008-2013). Earnings start to decline earlier than the quarter in which the job loss occurs and increase sharply in the subsequent quarters. The decline in earnings is more abrupt in the crisis period, fluctuating between 40 and 50 per cent. Earnings recovery is observed with a delay of more than two quarters, but the earnings gap between those who lost their jobs and those who are continuously employed never closes and remains at 15-20 per cent after two years of job loss.

Figure 1. Earnings losses of unemployed husbands and number of quarters since unemployment

Source: EU-SILC (2003-2013), Hellenic Statistical Authority. Authors’ calculations.

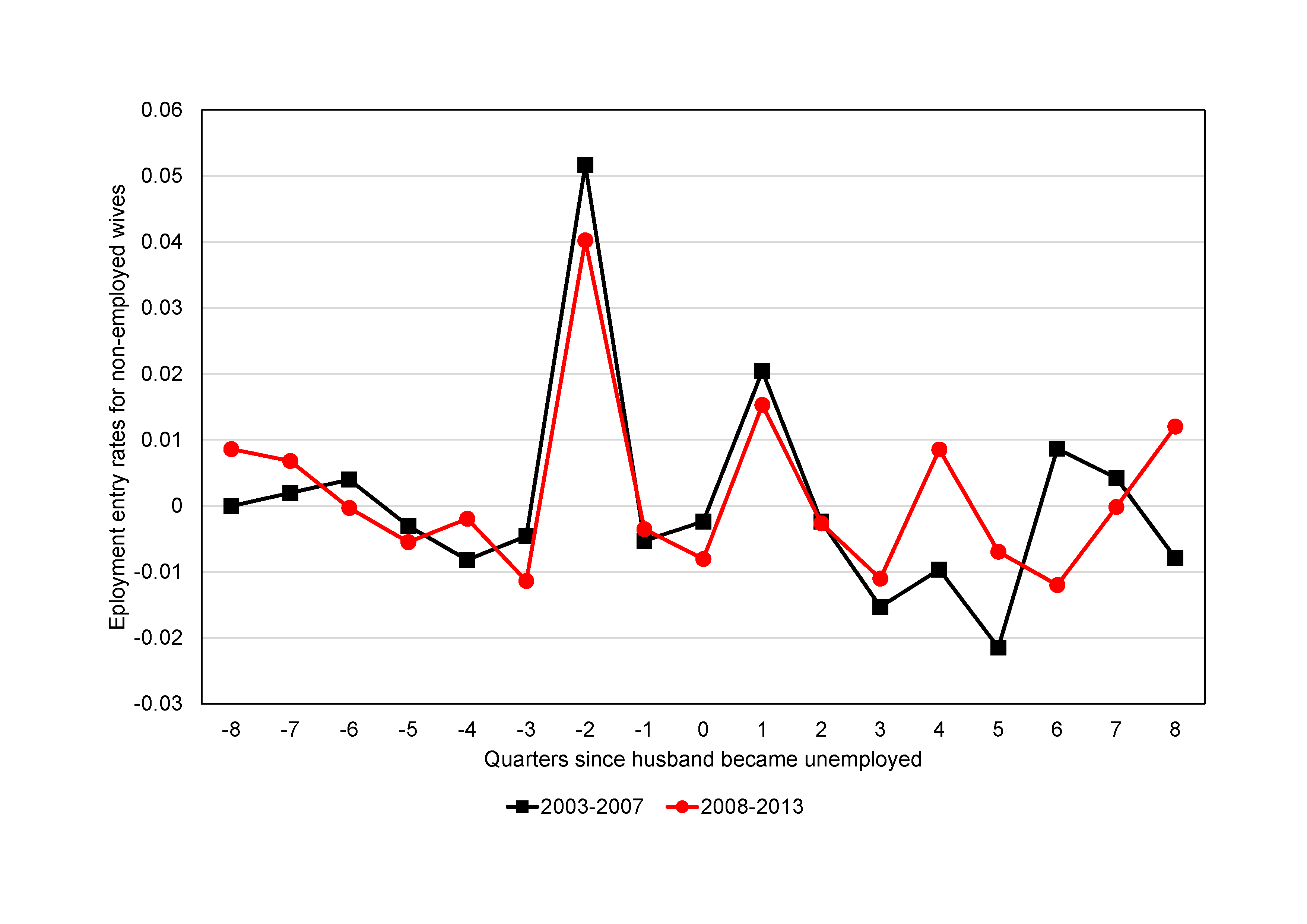

In addition, in the crisis period, non-employed wives whose husbands lost their jobs appear to increase the likelihood of entering the labour market (that is, actively looking for a job) by 8.2 per cent (monthly). This figure stood at 5.7 per cent in the pre-crisis period (2003-2007). Nevertheless, actively looking for a job in the crisis period is not accompanied by an increased likelihood of being employed. The probability of being employed is 0.7 per cent higher for the non-employed wives with unemployed husbands in comparison to non-employed wives with working spouses. In the pre-crisis period this figure stood at one per cent.

Focusing on the timing of the husband’s job loss, we found (Figure 2) that the non-employed wives of unemployed husbands in the pre-2008 period had, on average, 5 per cent higher probability of entering employment two quarters before their husbands’ job loss, and 2 per cent higher after one quarter. These probabilities are somewhat lower in the post-2008 period, highlighting the limited employment opportunities in the Greek economy during the crisis.

Figure 2. Wife’s employment entry and number of quarters since husband became unemployed

Source: EU-SILC (2003-2013), Hellenic Statistical Authority. Authors’ calculations.

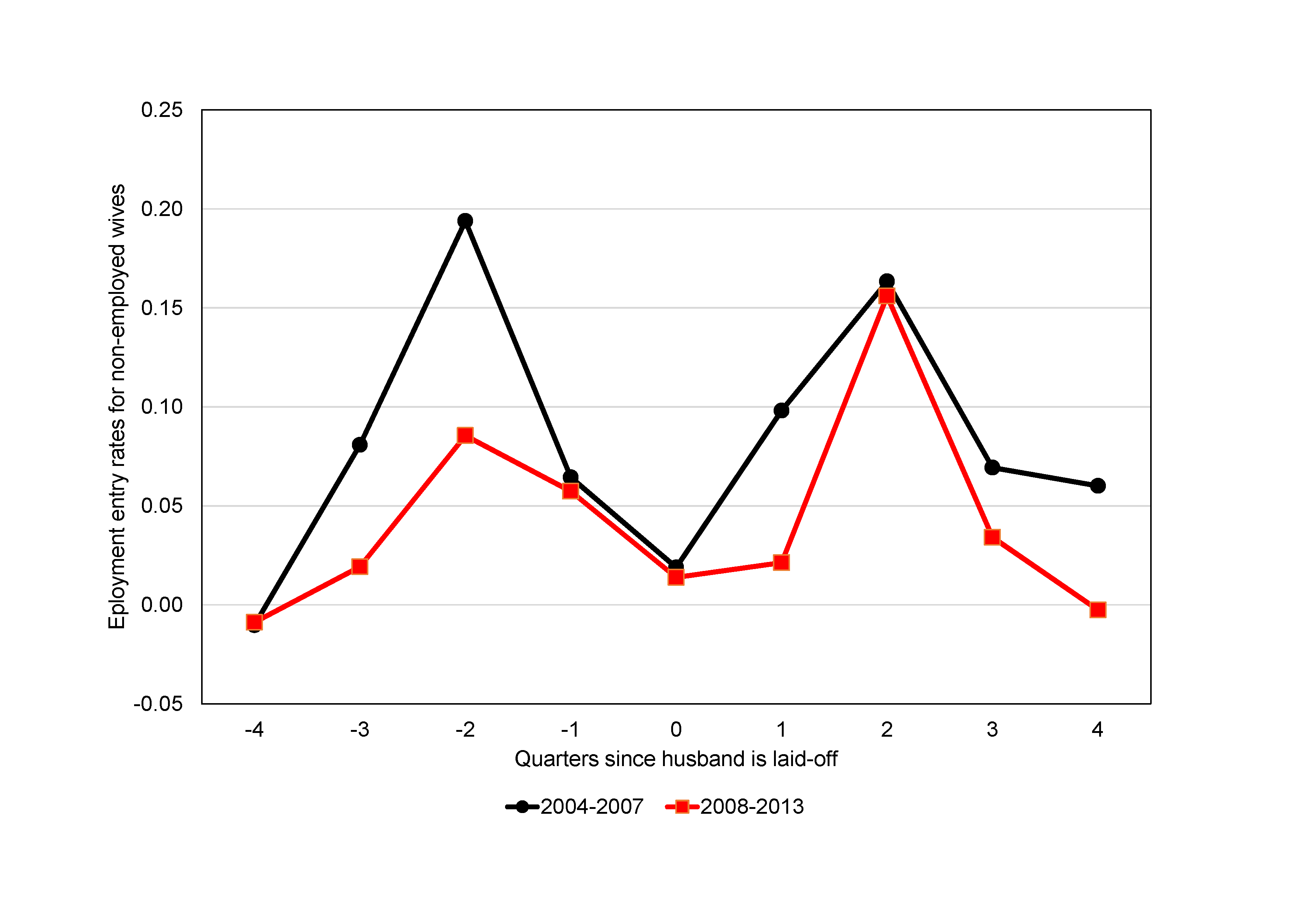

We have also investigated the labour supply responses of non-employed wives whose husbands are laid-off. Utilising data from the quarterly Labour Force Survey (LFS) for the period 2004-2015 we found that wives with jobless partners due to lay-offs have 15.1 per cent higher probability of entering the labour market but only 2 per cent higher probability of being employed. In the pre-2008 period these figures stood at 10.9 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively. The corresponding figures for the post-2008 period are as expected higher for labour market entry (13.5 per cent) and lower for employment entry (1.6 per cent).

Furthermore, we found that wives’ employment entry reaches a peak two quarters before the husband’s lay-off and two quarters following his displacement. We also observe that the effects are more pronounced in the pre-2008 period (Figure 3). Lastly, examining the employment entry of wives with laid-off husbands by their pre-displacement earnings we found that the wives of low income husbands (below median monthly earnings) have higher probability of entering employment compared to those with above median monthly earnings.

Figure 3. Wife’s employment entry and number of quarters since husband is laid-off

Source: LFS, 2004-2015. Hellenic Statistical Authority. Authors’ calculations.

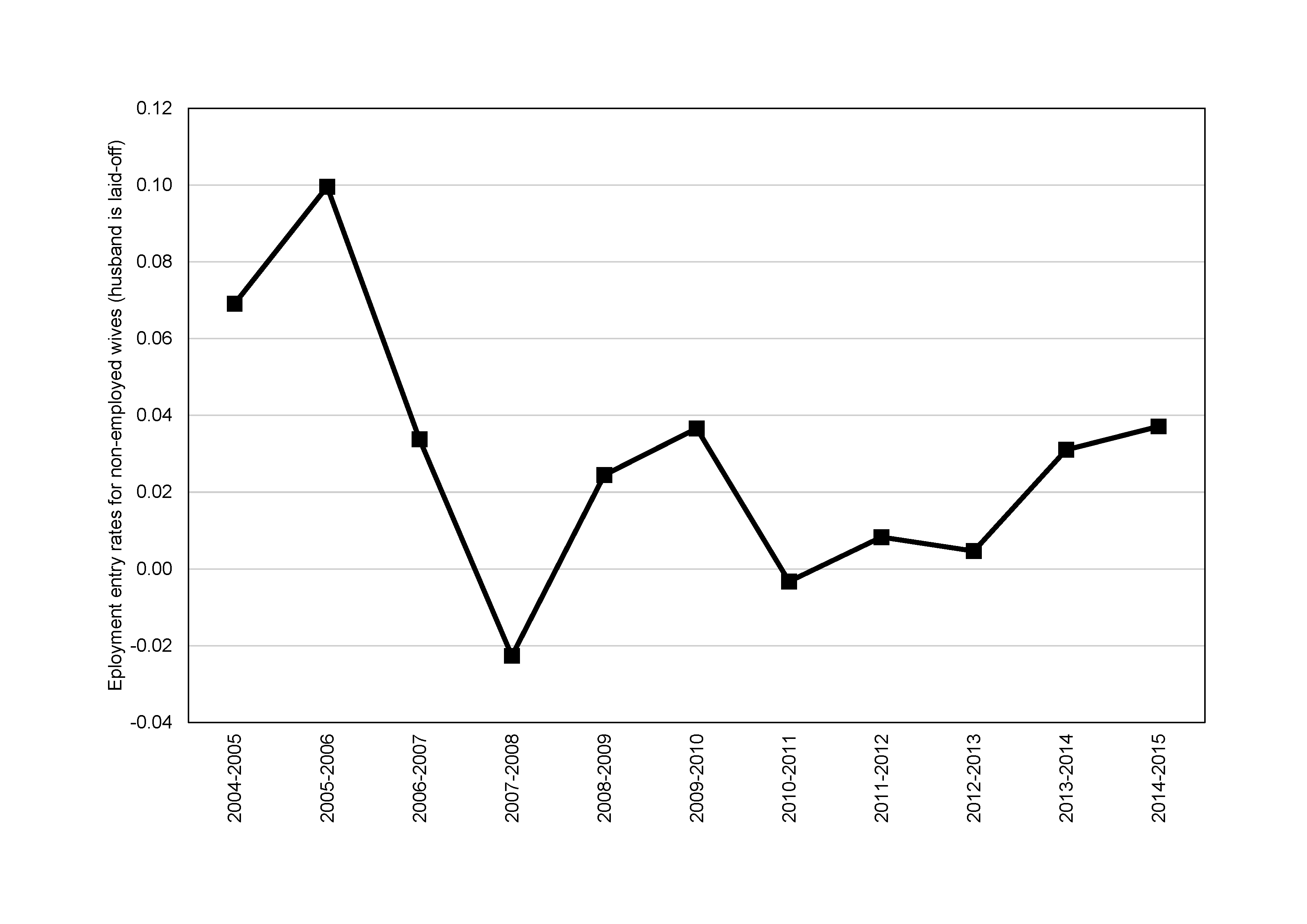

We also found that the income position of the family is improved when the non-employed wife enters employment. The couple’s monthly earnings are almost 20 per cent higher when the wife of the laid-off husband becomes employed (compared to those wives who do not enter employment). In the pre-crisis period this improvement was 13 per cent while in the post-crisis period it increased substantially and it stands at about 30 per cent. Thus, the relative income position of families in which the added-worker effect is present improves more during periods of limited employment opportunities (i.e., during the crisis). This could also explain the increased labour force participation of non-employed wives before and during the crisis. Nevertheless, it appears that the added worker effect became weaker in the post-2008 period (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The evolution of the “added worker effect” in Greece, 2004-2015

Source: LFS, 2004-2015. Hellenic Statistical Authority. Authors’ calculations.

Summing up, non-employed Greek wives whose husbands have become unemployed increased their job finding efforts but their chances of finding a job decreased considerably during the crisis. Thus, the “added worker effect” in the Greek case becomes smaller in the crisis years. In other words, women whose husbands lost their job have increased labour force participation rates but with little chances of entering employment (work for pay). This indicates that some women find jobs but because a lot more women start looking for employment, the employment/unemployment figures do not budge. In the meantime and from a policy perspective, the pressure for the establishment of social protection nets aiming at avoiding increased poverty rates and the emerging informalities in the Greek labour market keeps rising.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper The added worker effect of married women in Greece during the crisis (preliminary version), presented at the European Economic Association’s 31st Annual Congress in Geneva, August 2016.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review, the London School of Economics or the University of Minnesota.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Joan Daouli is Professor of Economics at University of Patras. Her main research interests are in labour economics. She holds a PhD in Economics from North Carolina State University

Joan Daouli is Professor of Economics at University of Patras. Her main research interests are in labour economics. She holds a PhD in Economics from North Carolina State University

Michael Demoussis is Professor of Economics at University of Patras. His main research interests are in microeconomics and labour economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from North Carolina State University.

Michael Demoussis is Professor of Economics at University of Patras. His main research interests are in microeconomics and labour economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from North Carolina State University.

Nicholas Giannakopoulos is Assistant Professor of Economics at University of Patras. His main research interests are in applied micro-econometrics and labour economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from University of Patras.

Nicholas Giannakopoulos is Assistant Professor of Economics at University of Patras. His main research interests are in applied micro-econometrics and labour economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from University of Patras.