Do resource booms enhance growth in a country or lead to a ‘crowding out’ of other tradable industries, such as manufacturing? Traditional theories suggest that crowding-out effects dominate. The idea is that gains from the boom largely accrue to the profitable sectors servicing the resource industry, while the rest of the country suffers adverse effects from increased wage costs, an appreciated exchange rate and a lack of competitiveness as a result of the boom.

In the research literature, such a phenomenon is commonly been referred to as ‘Dutch disease’, based on similar experiences in the Netherlands in the 1960s. But traditional studies of Dutch disease do not account for productivity spillovers between the booming resource sector and other non-resource sectors. We put forward a simple theory model that allows for such spillovers. We then quantify these spillovers empirically, allowing for measurement of both resource and spending effects through a large panel of variables.

Using mineral abundant Australia and petroleum rich Norway as representative cases studies, we find that a booming resource sector has positive effects on non-resource sectors, effects that have not been captured in previous analysis. The wider benefits for the economy are particularly evident when taking account of productivity ‘spillovers’ and ‘learning-by-doing’ between industries. The most positively affected sectors from a resource boom are construction and services. Yet, manufacturing also benefits, though less so than the other industries.

Augmenting traditional Dutch disease theories

Experience in resource-rich countries suggests that there may be important spillovers from the resource sectors to other industries. Norway is good example. As the development of offshore oil often demands complicated technical solutions, this could in itself generate positive knowledge externalities that benefit other sectors. And since these sectors trade with other industries in the economy, there may be learning by doing spillovers to the overall economy.

Traditional Dutch disease theories do not account for such spillovers. The model developed in this study does take account of them. We allow for direct productivity spillovers from the resource sector to both the traded and non-traded sector.

We further assume that there is learning-by-doing in the traded and non-traded sectors, as well as learning spillovers between these sectors. Hence, we extend the more traditional model of learning-by-doing with technology spillovers from the resource sector. To the extent that the natural resource sector crowds in productivity in the other sectors, the growth rate in the overall economy will also increase.

The positive effects of a resource boom

We test the predictions from our suggested theoretical model against data by estimating a dynamic factor model that includes separate activity factors for the resource and non-resource sectors in addition to global activity and the real commodity price.

This makes it possible to examine separately the windfall gains associated with resource booms (that is, volume changes) from commodity price changes, while also allowing global demand to affect commodity prices.

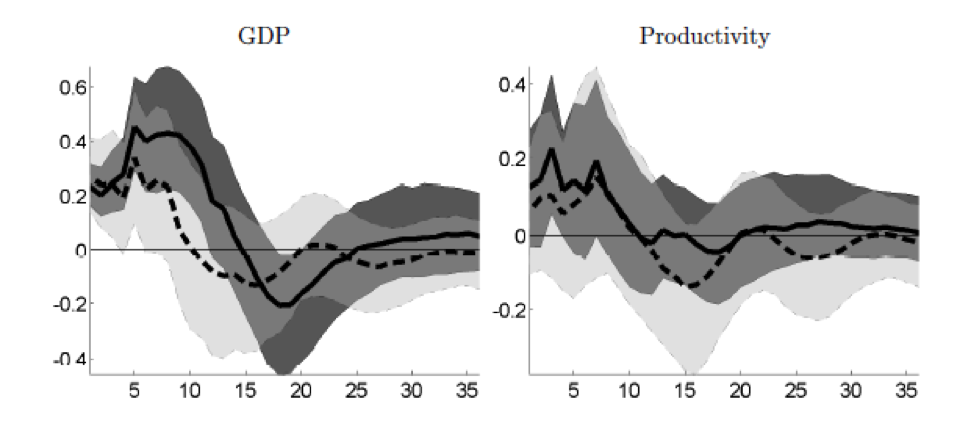

The main finding emphasises that there are large and positive spillovers from the exploration of natural resources to the non-resource industries in both Norway and Australia. In particular, in the wake of the resource boom, productivity, output and employment increase for a prolonged period of time in both countries, see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Australia and Norway: output and productivity responses to a resource boom

Note: In each plot, Norway is the solid line with the associated dark grey probability band, while Australia is the dotted line with the associated light grey probability band. The responses are displayed in levels of the variables. The resource boom shock is normalised to increase the resource activity factor by 1 per cent. The shaded areas (dark and light grey) represent 68 per cent probability bands, while the lines (solid and dotted) are median estimates.

The expansion in Norway is substantial; after one to two years, 25-30 per cent of the variation in non-resource GDP is explained by the resource boom, while the comparable numbers are 43-50 per cent for productivity. In Australia, the expansion is more modest: 10-15 per cent of value added in non-mining is explained by the resource boom, while 5-6 per cent of productivity is explained by the same shock.

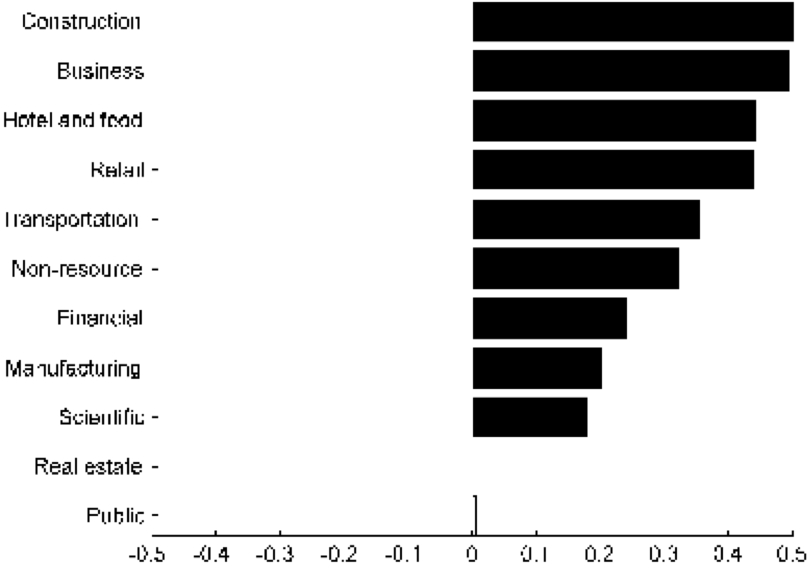

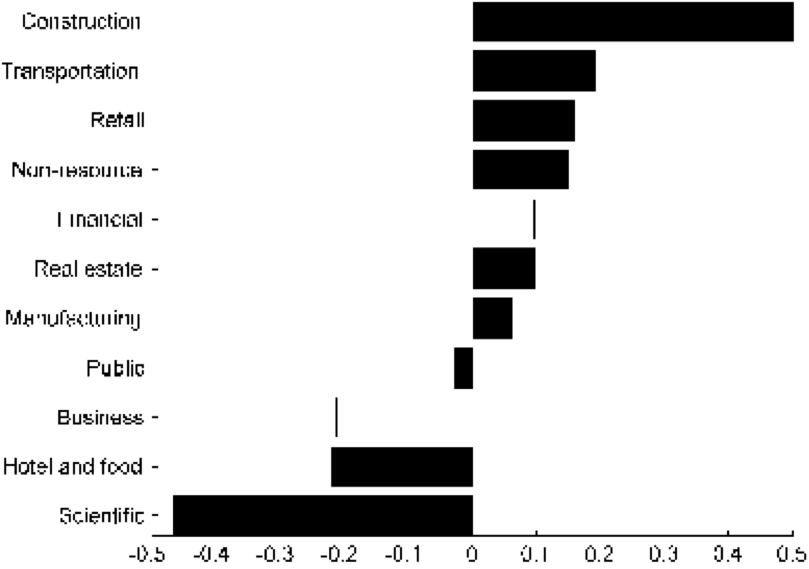

Examining the different industries, we confirm that value added and employment increase in the non-traded sectors relative to the traded sectors, suggesting a two-speed transmission phase. This is in particular evident in Australia. The most positively affected sectors are construction and business services. Still, and in contrast to the predictions from the traditional Dutch disease theories, manufacturing also benefits from the resource boom, although less so than the other industries – see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Australia and Norway: sectoral responses to a resource boom

Value added in Norway

Value added in Australia

Note: Each plot displays the quarterly average of each sector’s response (in levels) to the resource boom shock. The averages are computed over horizons 1 to 12. The resource activity shock is normalised to increase the resource activity factor by 1 per cent. White bars indicate that the shock explains less than 10 per cent of the variation in the sector.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper Boom or Gloom? Examining the Dutch Disease in Two-speed Economies, Economic Journal, Volume 126, Issue 598, December 2016, Pages 2219–2256. For a previous working paper version, see here.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Norway’s Ekofisk oil platform, y Knudsens Fotosenter/DEXTRA, under a CC BY 4.0 licence, via Wikimedia Commons

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Hilde C. Bjørnland is Professor of Economics at BI Norwegian Business School and Director at the Center for Applied Macro-and Petroleum economics (CAMP). She is also scientific advisor at the research department of Norges Bank and member of the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council. Her main research interests are applied macroeconomics and time series. Special interests include the study of natural resources, business cycles, and monetary and fiscal policy. Dr. Bjørnland has published extensively in top international journals. She is also the co-author of the book: “Applied Time Series For Macroeconomics”. Email: hilde.c.bjornland@bi.no

Hilde C. Bjørnland is Professor of Economics at BI Norwegian Business School and Director at the Center for Applied Macro-and Petroleum economics (CAMP). She is also scientific advisor at the research department of Norges Bank and member of the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council. Her main research interests are applied macroeconomics and time series. Special interests include the study of natural resources, business cycles, and monetary and fiscal policy. Dr. Bjørnland has published extensively in top international journals. She is also the co-author of the book: “Applied Time Series For Macroeconomics”. Email: hilde.c.bjornland@bi.no

Leif Anders Thorsrud is a Senior Researcher in Monetary Policy Research at Norges Bank and Researcher II at the BI Norwegian Business School and Center for Applied Macro and Petroleum Economics. He obtained his Ph.D. at the BI Norwegian Business School in 2014. Dr. Thorsrud’s research on forecasting and energy economics has been published in top field international journals. Currently his research agenda centres on how unstructured data sources can be used to understand macroeconomic fluctuations. He co-authored the book: “Applied Time Series For Macroeconomics”. Email: leif.a.thorsrud@bi.no

Leif Anders Thorsrud is a Senior Researcher in Monetary Policy Research at Norges Bank and Researcher II at the BI Norwegian Business School and Center for Applied Macro and Petroleum Economics. He obtained his Ph.D. at the BI Norwegian Business School in 2014. Dr. Thorsrud’s research on forecasting and energy economics has been published in top field international journals. Currently his research agenda centres on how unstructured data sources can be used to understand macroeconomic fluctuations. He co-authored the book: “Applied Time Series For Macroeconomics”. Email: leif.a.thorsrud@bi.no