Rising inflation has added pressure on the Bank of England’s policymakers to respond by tightening monetary policy. But, Costas Milas asks, will they do so?

Quite often, students in economics are telling truths that policymakers do not necessarily want to hear. Following a recent lecture of mine in “Financial Crises and Defaults”, a third-year student made a challenging remark: “Sir, I cannot understand why the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members are targeting CPI”. The remark was rather frustrating given that I had spent a whole hour discussing the benefits of inflation targeting both in the UK and around the world. “Why is that?”, I responded in a very polite manner. “Because the Bank’s policymakers Cannot Predict Inflation (CPI)!!!”

What triggered such a… ”disrespectful” remark towards the Bank’s forecasting record? And are the nine MPC members about to make a mistake by increasing UK interest rates in response to rising inflation?

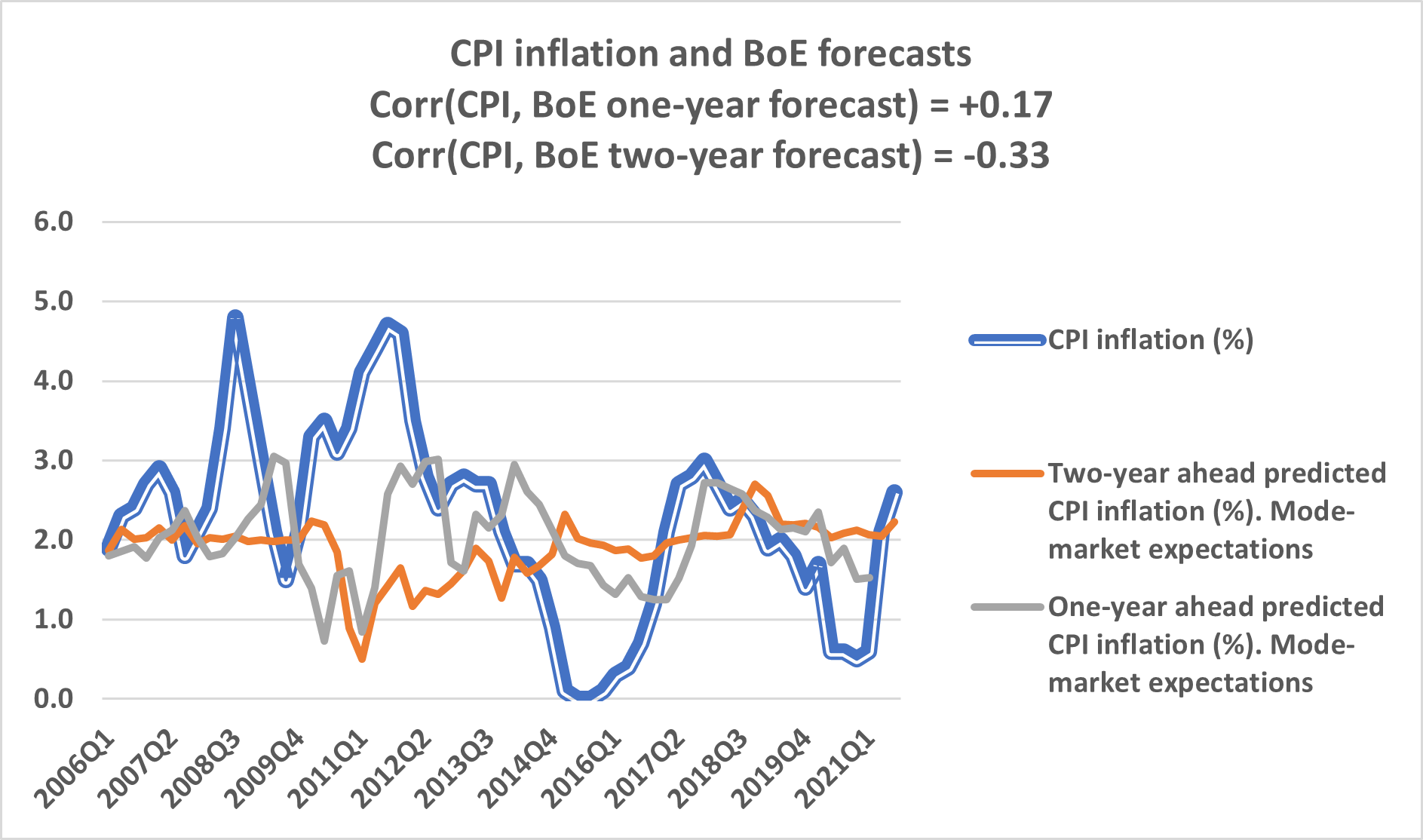

The Bank of England aims at hitting a 2% inflation target approximately two years into the future based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation. Figure 1, which also features heavily in my lecture notes, explores the ability of the Bank of England to forecast UK CPI inflation over the 2006-2021 period. To do so, I plot together the one-year and two-year inflation forecasts (with reference to the ‘mode’ or most likely outcome in the Bank’s distribution of forecasts) together with the actual inflation outcome under the assumption of market expectations of interest rates.

Figure 1. Bank of England’s inflation forecasts and actual inflation outcome

Data sources: BoE forecasts from successive Monetary Policy Reports. CPI inflation from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Notice the following:

First, over the last 15 years, the Bank of England has, on average, under-predicted one-year ahead CPI inflation by 20 basis points per annum. The Bank’s forecasting record is slightly worse two years down the road. Indeed, the Bank has under-predicted two-year ahead CPI inflation by an average of 32 basis points per annum.

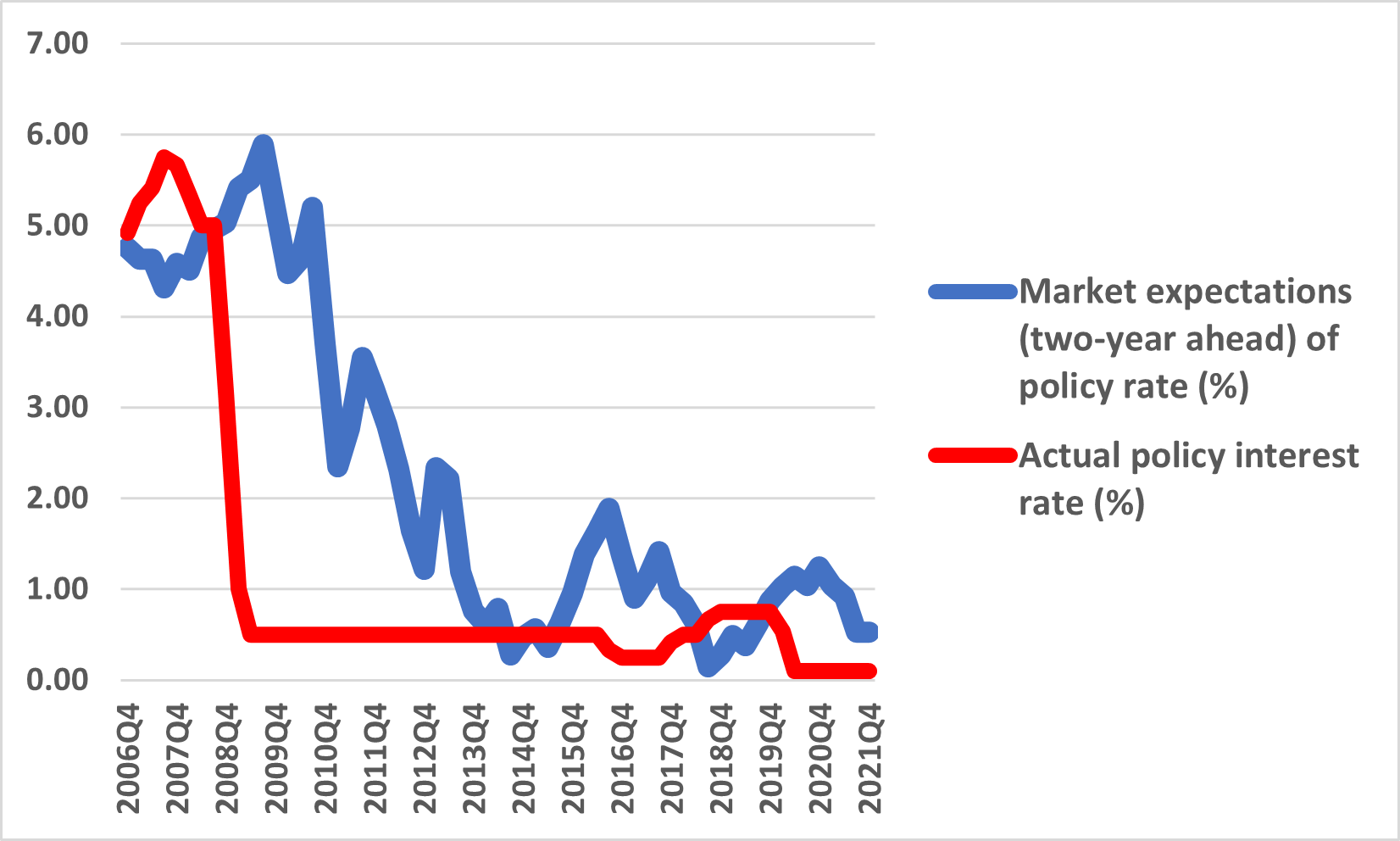

Second, the correlation between the Bank’s one-year forecast and actual inflation is very weak (and equal to 0.17). Even worse, the correlation between the Bank’s two-year forecast and actual inflation is negative (and equal to -0.33). In other words, although the Bank targets CPI inflation two years into the future, actual inflation moves in opposite direction to the forecast. This is the very forecast that takes into account what financial markets think about the future path of interest rates in the UK. Quite a striking observation if one considers that financial markets are currently… worried that the BoE might make a “mistake” in tightening monetary policy too fast following rising inflation. In fact, from Figure 2, which plots the market expectations of UK interest rates two years ahead together with the actual policy interest rate, financial markets have consistently been mistaken. Indeed, financial markets have over-predicted the Bank’s policy rate by an average of 1.1 percentage points per annum.

Figure 2. Market expectations of BoE’s policy rate and actual policy rate

Data sources: Market expectations of interest rate from successive BoE Monetary Policy Reports. Policy rate from the BoE.

Mistaken interest rate expectations held by financial markets might have been related, at least to some extent, to lack of communication clarity coming from the Bank of England. After all, former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney was, in 2014, called the “unreliable boyfriend” because of his conflicting messages on the future path of interest rates. Whether or not financial markets are willing to blame their mistaken interest rate expectations on the Bank itself, there is definitely room for improvement. Indeed, the Bank needs to strengthen its own communication policy. Rather than conditioning its forecasts on what financial markets expect, the Bank could follow other central banks like the Reserve Bank of New Zealand or the Swedish Riksbank in producing (in a probabilistic manner) its own future path of interest rates.

Until the Bank’s policymakers decide to take this “radical’ step, let’s keep in mind that the Bank has been tasked by the chancellor of the exchequer to target CPI inflation. The Bank has not been tasked to target only demand-driven inflation or only supply-driven inflation. This is an important point to make because, even if we are willing to accept the very valid point that supply-side constraints are currently adding to inflation pressures, these very constraints can also push wages higher. In other words, the Bank of England will have to react, sooner rather than later.

That said, weakening GDP prospects in light of rising energy costs, lack of speed in the rollout of the ‘booster vaccine’, rising national insurance taxes, and a planned rise in the corporation tax might, among other things, make the Bank unwilling, for now, to tighten monetary policy. Bank of England policymakers can also point out that since the start of quantitative easing (in March 2009), UK inflation has been below 1% some 22% of all times and above 3% ‘only’ 19% of all times.

I am focussing on the 1% and 3% thresholds that trigger an explanation letter by the Bank’s governor to the chancellor of the exchequer. So MPC members can reasonably argue that there has been a slight bias in favour of undershooting the target and, therefore, since they still (?) view inflation as only transitory, they can allow for some overshooting bias before tightening policy. The latest inflation figure, however, might be telling us what ancient Greeks used to say. That is, “nothing is more permanent than the temporary”…

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post represents the views of the author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Robert Bye on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.