Finally, good news from the Eurozone. Unemployment rates fell to 9.5% in February 2017. According to Eurostat, this is the lowest rate since May 2009. The 19 countries that have adopted the common currency are thus returning back to the unemployment level they experienced before the outbreak of the Eurozone crisis. In the last 12 months, the Eurozone recovery has lifted 1.25 million people out of unemployment.

This long-awaited decrease in unemployment is highly welcome; every person back in work is good news, even though it took nine years to recover. Yes, many economists believe that the recovery could have been faster with much less pain if there had been less initial emphasis on austerity and less reluctance “to do what it takes” at the ECB before Mario Draghi made that move in 2012. But that said, the Eurozone must now look forward.

So, is the worst over? Is wealth and prosperity – the ultimate promise of the EU to its citizens – finally coming back to the Eurozone? And is the fragility of the Eurozone that brought the crisis and the dramatic rise in unemployment a thing of the past?

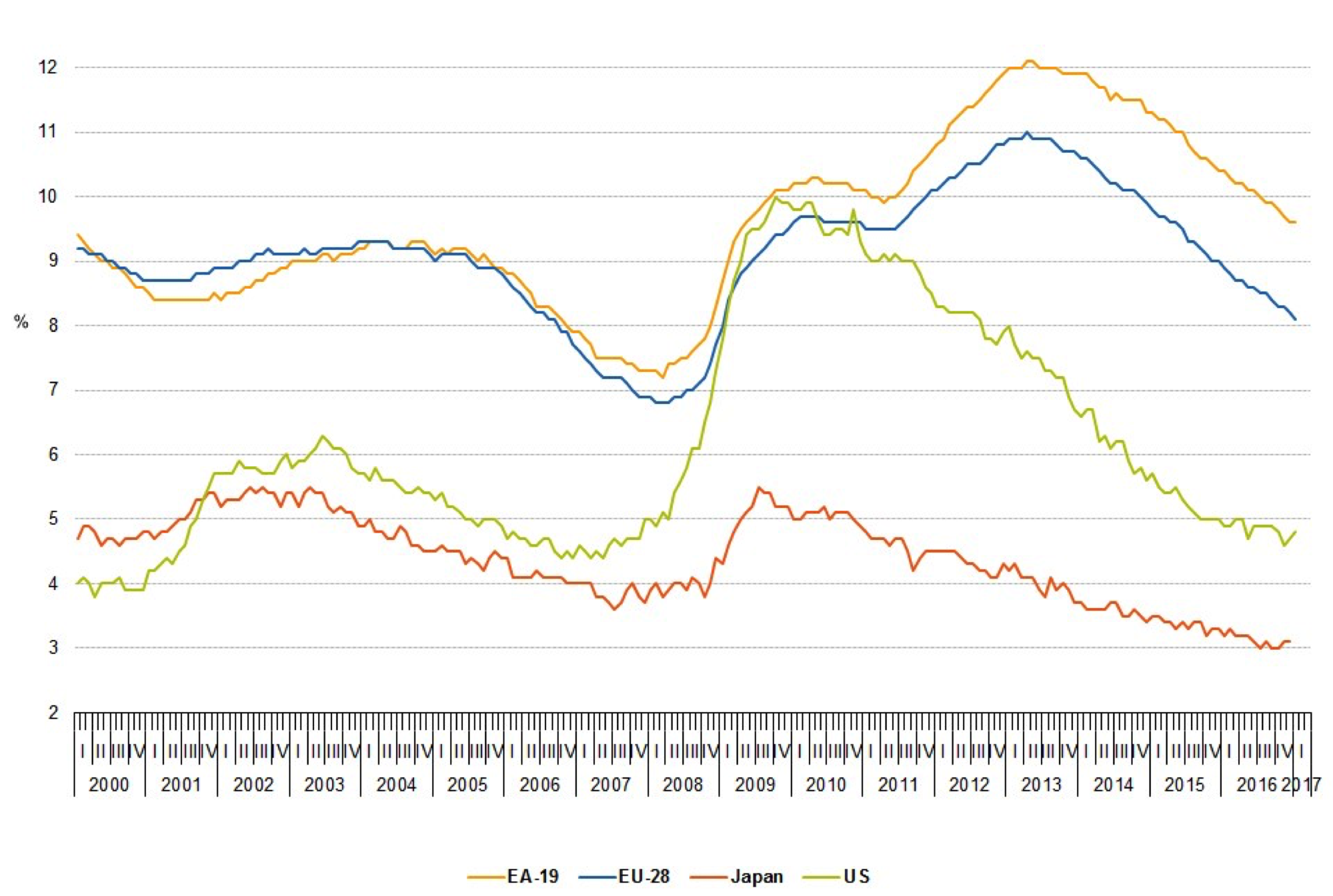

To start with: Yes, the worst is over, but ‘better’ is not yet ‘good’. First, the benchmark should not be 2009, but 2007, the year before the great financial crisis, when the unemployment rate stood at around 7.5%. Second, even this number was back then considered as being much too high, pointing at structural unemployment problems in several countries.

Figure 1: Unemployment rates in the EU, Eurozone, Japan and the United States (2000 – February 2017)

Note: Eurostat figures, seasonally adjusted.

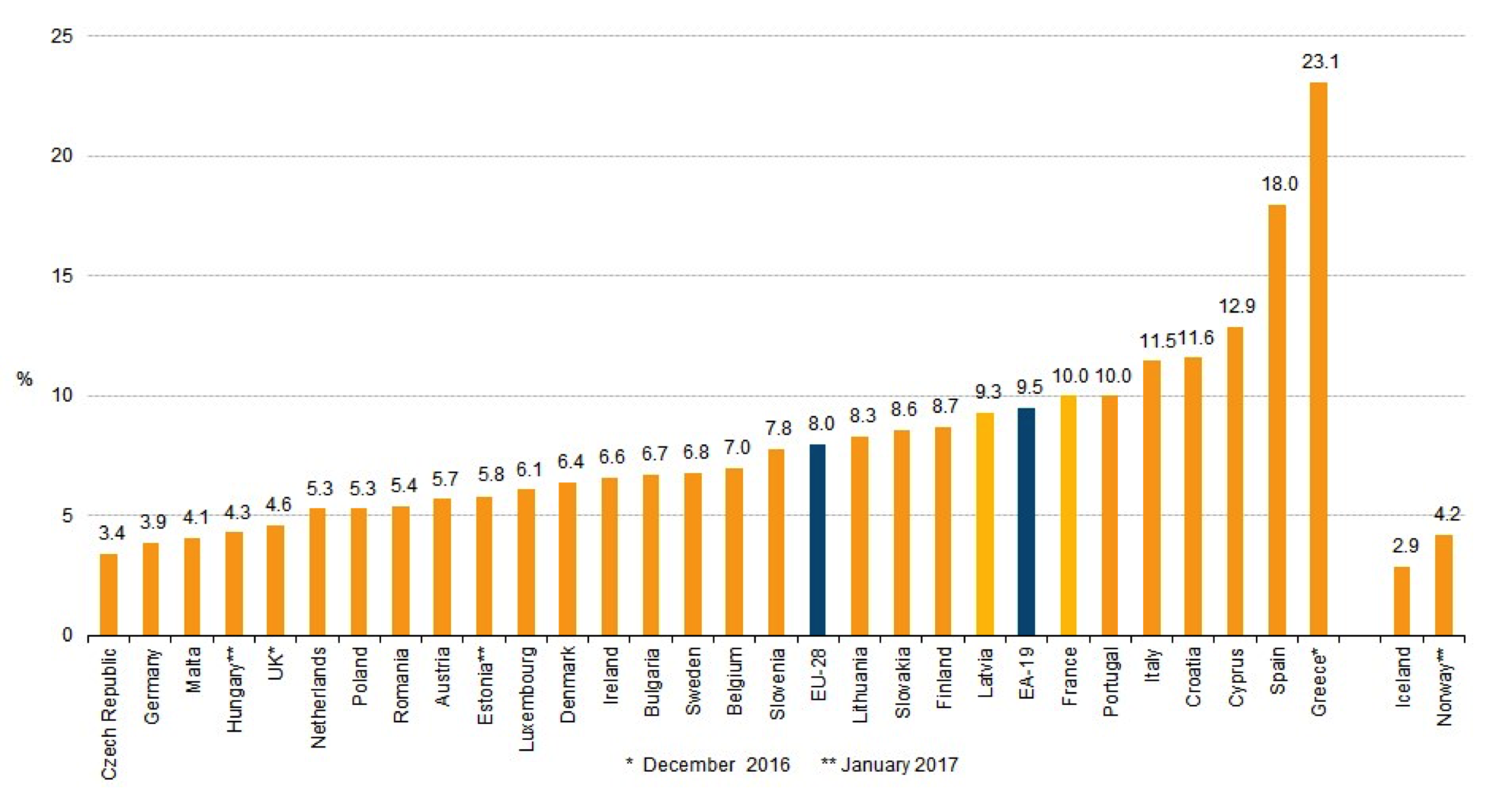

Third, the positive data should not mask the heterogeneity across countries. While some of the crisis countries, like Ireland, Portugal and Spain, show the biggest improvements, the unemployment situation in Italy (11.5%) and France (10.0%) has hardly improved and the rates have remained stubbornly high. And with unemployment rates of 18% in Spain and some 23% in Greece, it is clear the situation is not yet healthy.

Figure 2: Unemployment rates in European states (February 2017)

Note: Eurostat figures, seasonally adjusted.

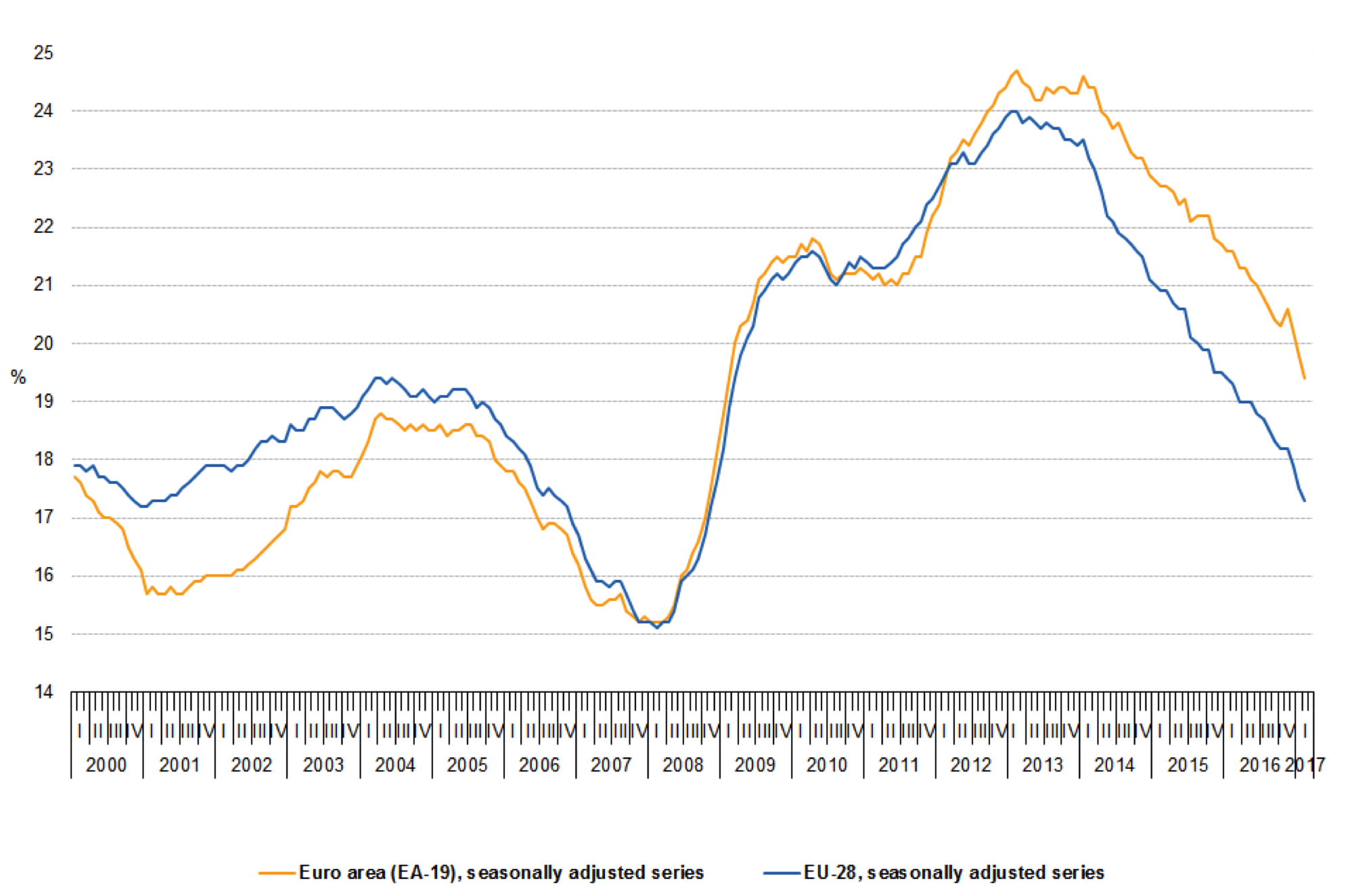

Finally, this is particularly true with respect to youth unemployment, where the rate is still standing at 19.4% with over 2.7 million young people out of work, a problem that is especially severe in Greece (45.2), Spain (41.5%), Italy (35.2%), Portugal (25.4) and France (23.6).

Figure 3: Youth unemployment rates in the EU and the Eurozone (2000 – February 2017)

Note: Eurostat figures, seasonally adjusted.

In sum, the good news is not enough and more needs to done. On the one hand, national labour market policies need to provide better employment incentives, and on the other hand, it is now important to keep and support the momentum of the Eurozone recovery.

In the latter respect, the policy stance of the European Central Bank (ECB) will continue to play a major role. For the time being, the ECB seems to be determined to continue with its quantitative easing programme, as Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board, has indicated recently: “while we are certainly seeing a firming, broadening and more resilient economic recovery, we still need to create a sufficiently broad and solid information basis to build confidence that the projected path of inflation is robust, durable and self-sustained.“

This message should be read against the recent fall in the Eurozone inflation rate below the ECB target of 2% to an estimated 1.5% in March. Nonetheless, ECB communications are already making clear that the times of zero interest rates will not last forever: “I hope that euro zone governments know that interest rates will not stay at current levels”, said Benoît Cœuré, also a Member of the ECB’s Executive Board, on 3 April.

Hence, while the worst is over, it remains important that both the ECB and national governments work in tandem to allow for a speedy return of the Eurozone to its full potential. According to the latest IMF estimates, the Eurozone economy is still 0.84% below its potential and expected to reach it only in 2020. But maybe the expected new IMF forecasts, which are due this month, will also surprise us with good news.

Will the Eurozone therefore deliver on the grand European promise of promoting wealth and prosperity? The answer here is, again, that much more needs to done. The long-term growth over the past decade, as well as the future prospects, revolve around GDP growth rates of some 1.5% per annum. As “medium-term prospects remain mediocre” in the eyes of last year’s IMF report on the Eurozone, the prospects for returning to the unemployment levels of before the great financial crisis remain low.

The financial crisis and the subsequent Eurozone crisis have slowed-down the long-term growth path far below what was expected before the crises. Low investment rates and de-qualifying long-term unemployment have taken a huge toll on the potential output of the Eurozone economy. These secular stagnation tendencies need to be addressed to deliver on the European prosperity promise and to create more well-paid jobs. In particular, public investment will have to play an important and bigger role. But given the limited fiscal space in many highly indebted member states, joint European investment initiatives will be vital for this. The Juncker Plan is a step in the right direction, yet more is needed for “making the Eurozone great again”.

Finally, is the Eurozone now waterproof against a new financial crisis? To some extent, yes. Much has been done, including the establishment of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the first steps towards a banking union. But this might not be enough. The Eurozone is still a collection of countries, which would react quite differently if new shocks hit those in the currency union.

The pattern of this heterogeneity seems to have changed too, though. The old view of two separate groups of core and periphery countries, the former comprising Germany and its close neighbours, the latter formed by southern European countries, dubbed the “Club Med”, no longer appears to exist. According to a recent research paper, Germany’s reaction to shocks is now closer related to some Club-Med countries than to core countries like France or Belgium. If this is correct, more joint risk sharing in the Eurozone is needed just at a time when the fault lines of common interests in the Eurozone are changing, thus making joint actions politically more difficult.

Nevertheless, to make an asymmetric monetary union work, it is important above all that full banking union complements the monetary union. While the first steps towards a banking union have been taken, more needs to be done especially regarding a joint resolution mechanism and installing a joint deposit insurance system. Yet, the political appetite for such joint risk sharing is low, not least in countries like Germany prior to major elections.

In sum, the Eurozone is on a good track. The danger of the good news is that they may calm Eurozone policy-makers down. But the opportunity is that a broad-based recovery could also contribute to healthier banking systems, thus facilitating the necessary reforms in the political sphere.

The “good news” also carries the message that it took nine years to return to pre-crisis unemployment levels. This should encourage the Eurozone to increase efforts to create a workable and stable monetary union, which is no longer a potential threat to European citizens’ jobs, wealth and prosperity, but a safe haven in a world of increasing economic and political insecurities.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post was published originally by LSE Europp.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Euro, by geralt, under a CC0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Harald Sander holds a Jean Monnet Chair and is Professor of Economics at Technische Hochschule Köln and at Maastricht School of Management.

Harald Sander holds a Jean Monnet Chair and is Professor of Economics at Technische Hochschule Köln and at Maastricht School of Management.