Reacting to political, financial and societal pressures, the NHS is an ever-evolving organisation, with its staff experiencing change at an increasing rate. So common, change is now seen to be a fact of working life within the NHS and therefore change management a key aspect of any manager’s role.

When we talk about change management in the NHS, it is most commonly associated with the psychological or human aspect of change, otherwise known as transition. It is argued that the way in which people experience change is just as important to the success of the change effort as the physical implementation of the change itself. Subsequently, training regarding how to manage structural change and emotional transition is now included within most management and leadership development courses in the NHS, with some providers even developing their own change management training materials to support this.

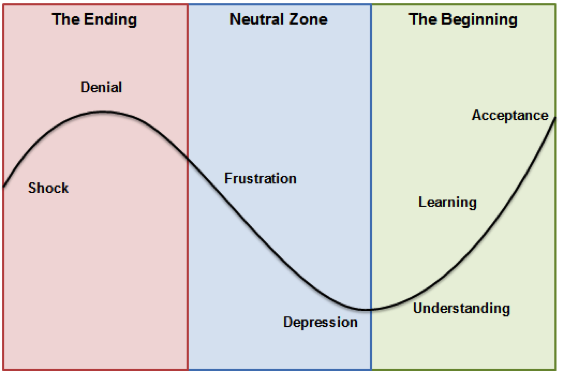

The key tools advocated for within training are Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ Change Curve and William Bridge’s Transition Model. These models are each intended to support managers to better understand the emotional journey their staff are likely to go through when faced with change and are therefore frequently presented together. By managing these emotions correctly, managers should be able to reduce resistance to change and in so, more effectively carry out their roles.

NHS managers are however still considered to manage change poorly; it is argued here that these models may be just the reason why.

It perpetuates feeling of extreme negativity

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ original work was developed following her observations of those who were terminally ill, situating the model in a very specific context; subsequently, each of the emotions presented in the losing or letting go section of the model are highly negative. In so, the model fails to appreciate, or present, the heterogeneous nature of organisational change or the array of possible reactions to this, leading managers to easily make a number of assumptions that may negatively affect their change efforts.

Firstly, this one-sided presentation of emotions allows for the assumption that all change will lead to initial resistance. There are no competing or complimentary models that position employees as welcoming of change, failing to present employees as those who may be willing to support or shape change. While some employees may be upset their status quo is changing, for others a change in circumstance may be positive and ignoring this possibility places managers at risk of failure to recruit early adopters, supporters and change agents, reducing positive action for change and therefore effectiveness of their change efforts.

Secondly, the crude and extreme nature of the emotional scale fails to recognise the nuances that may be present, representing employees as a homogenous group. This places managers at risk of developing simplistic communications plans that may alienate, or even anger, some groups within the organisation, rather than satiate or engage them.

It supports disempowerment

Developed over 50 years ago, the cultural context in which Kübler-Ross’ model was established was very different to the one of patient empowerment and involvement we now strive for today. The lack of a cultural update leads to this model working to disempower staff in ways that can be potentially very damaging to any change effort; by mapping it across to a modern day business context, managers are at risk of adopting a parent/child relationship with their staff, reminiscent of healthcare delivery in the last century.

Firstly, the wide acceptance of this model allows an expectation of a lack of productivity during what is known as the depression or neutral stage. It assumes that people will lose productivity and interest in the process, in so providing managers with an excuse to ‘do’ change to people, rather than include them in it. This is then exacerbated by the fact the model reduces employees to their emotions, presenting the most important aspect of the human element of change management as the management of potentially volatile feelings; it allows managers to ignore other positive alternatives such as the discovery and utilisation of human capital, or uncovering of productive criticism, both of which could support managers to more successfully implement the change itself.

It allows uncertainty and confusion

Finally, by following Bridge’s Transition Model, managers may actually be at risk of bringing about their own self-fulfilling prophecy. Accepting and advocating for feelings of uncertainty and confusion through the outlining of a ‘neutral’ zone, the model claims employees will spend a certain amount of time having to readjust their view of their world in relation to the change in place.

Managers must be extremely careful however not to use this presentation of inevitable confusion, purposefully or not, as an excuse to demonstrate bad management practices that fail to mitigate against, or reduce this unproductive state. Managers must ensure they do not prematurely communicate change, or fail to address the finer details of change because they believe the answers to employee’s questions are not required, promoting confusion, because confusion is expected. These approaches to change will only prolong the neutral stage, making it difficult for employees to move past this into a state of acceptance and movement toward the new.

Taking all of this into account, any manager embarking on a change journey must be aware that while the model can be utilised to support understanding of some reactions to change, it is not a certified blueprint. Applying it to all staff will inevitably hamper change efforts through the alienating, disempowering or discounting of those staff that could and may want to be key players in shaping and promoting a new future.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Surgery, by sasint, under a CC0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Polly Pascoe is a senior manager in the NHS, focusing on quality assurance and knowledge productivity. She is also currently a PhD candidate at the University of Bradford, studying support mechanisms for evidence-based management.

Polly Pascoe is a senior manager in the NHS, focusing on quality assurance and knowledge productivity. She is also currently a PhD candidate at the University of Bradford, studying support mechanisms for evidence-based management.

Hey LSE Business Review Editors,

My name is Martin and I am the CEO & Co-Founder of Cleverism.com — a leading educational website that helps people actually get their dream job (we write super actionable and helpful career guides :-).

I stumbled upon your post on “To improve change management, the NHS needs to discard outdated models” and I thought it was very insightful.

Over the last 2 weeks I wrote probably the most actionable and helpful guide on everything people ever wanted to know about Kubler-Ross change curve, Relevance and applications of Kubler-Ross Change Curve in Business etc.

Change is an inevitable part and truth of life, and there is no running away from it. If change is well planned and formulated, it can produce positive results but even in spite of planning, change is hard to incorporate, accept and appreciate. This article shall throw light on the Kubler-Ross Change Curve that is the most reliable tool to understand change. The Kubler-Ross Change Curve can be effectively used by business leaders to help their workforce adapt to change and move towards success.

In this article, we explore 1) what is Kubler-Ross Model, 2) the applications of the Kubler-Ross Change Curve, and 3) variations of change curve concepts. Any chance you’d include our actionable guide on “Kubler-Ross Change Curve” (https://www.cleverism.com/understanding-kubler-ross-change-curve/) in your awesome article (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2017/06/07/to-improve-change-management-the-nhs-needs-to-discard-outdated-models/)?

Have a lovely day and keep up the good work,

Martin

CEO Cleverism