Imagine you receive a phone call from someone who says they represent your bank. You are eligible to receive some free gifts, they say: gas coupons, airline savings vouchers, hotel accommodations. To get these free gifts, you simply need to verify your bank account number: they read the first nine digits and you just need to read the rest from the bottom of a check. Perhaps not realizing that the first nine digits are in fact publicly available, and that the person on the phone does not actually already have your checking account number, you reveal your number. They then proceed to enroll you into effectively worthless subscription programmes, charging your checking account every month until you take action to quit.

This is what happened to nearly 1 million people.

After thousands of these consumers complained to US law enforcement agencies and the Better Business Bureau, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sued the company over its deceptive practices. The resulting lawsuit against the fraudulent firm created a situation akin to an experiment: comparable groups of consumers enrolled in the fraudulent subscription programmes were assigned to make the same decision in different ways. Some consumers’ subscriptions were cancelled by default, while others had to cancel actively by making a phone call or mailing a form.

Along with coauthors Robert Letzler, Ryan Sandler, Isaac Knowles, and Luke Olson, we find that cancelling subscriptions by default increased cancellations to 99.8 per cent, 63.4 percentage points more than requiring active cancellation. We also find that consumers residing in poorer, less educated neighbourhoods were more likely than average to cancel prior to the lawsuit but were less likely to actively cancel in response to a complex, five-paragraph letter. These results suggest psychologically and behaviourally informed policies can improve consumers’ well-being—corroborating evidence from 2017 Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler and many others—but that the effectiveness may vary by demographics.

Between 2000 and 2007, Suntasia, a fraudulent telemarketing firm, charged hundreds of thousands of consumers monthly for essentially worthless subscriptions. Consumers paid Suntasia an average of $239 over the course of their subscriptions, totaling over $171 million across consumers. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued the firm in 2007, temporarily closing it down.

At that point, the court faced a question: what to do with the consumers currently enrolled in the subscription programmes? The FTC pushed for one default: cancel all consumers’ subscriptions unless they took action to continue them. The firm pushed for a different default: let consumers’ subscriptions continue unless they cancelled. Ultimately, the court split the difference: they put one group of consumers into one default, a second group of consumers into the other default, and sent both groups a somewhat complex, five-paragraph letter informing them of the FTC case, the default, and how they could overrule the default if they wanted.

Specifically, under the court order, consumers enrolled prior to February 1, 2007 received a letter telling them their subscriptions would continue by default: these consumers had to take action (fill out and mail a form or make a phone call) to cancel their subscriptions. In contrast, consumers enrolled after February 1, 2007 were sent an otherwise identical letter informing them their subscriptions would be cancelled by default: these consumers had to take action to continue their subscriptions. Given that very few consumers ever used any features of the subscriptions, nearly every subscriber would have been best off cancelling as soon as possible.

So what happened?

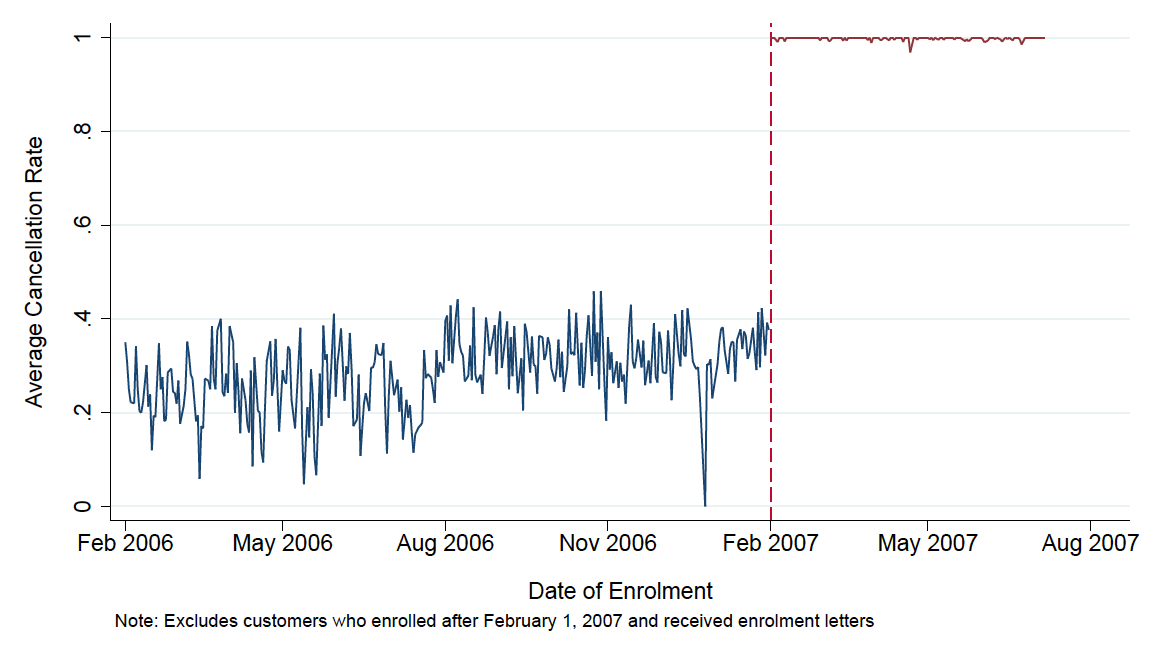

It turns out that the default had a massive effect. Subscribers assigned to the good default (having their subscription be automatically cancelled) were almost certain to escape the fraudulent firm: 99.8 per cent escaped (see Figure 1). Good news for those consumers!

But what about the people in the bad default—those who had to call or mail in a form to cancel their fraudulent subscription? With hundreds of dollars on the line, didn’t everyone pick up a phone or a pen, override the default, and cancel their subscription?

Figure 1. Cancellation rate of Suntasia’s subscription scheme

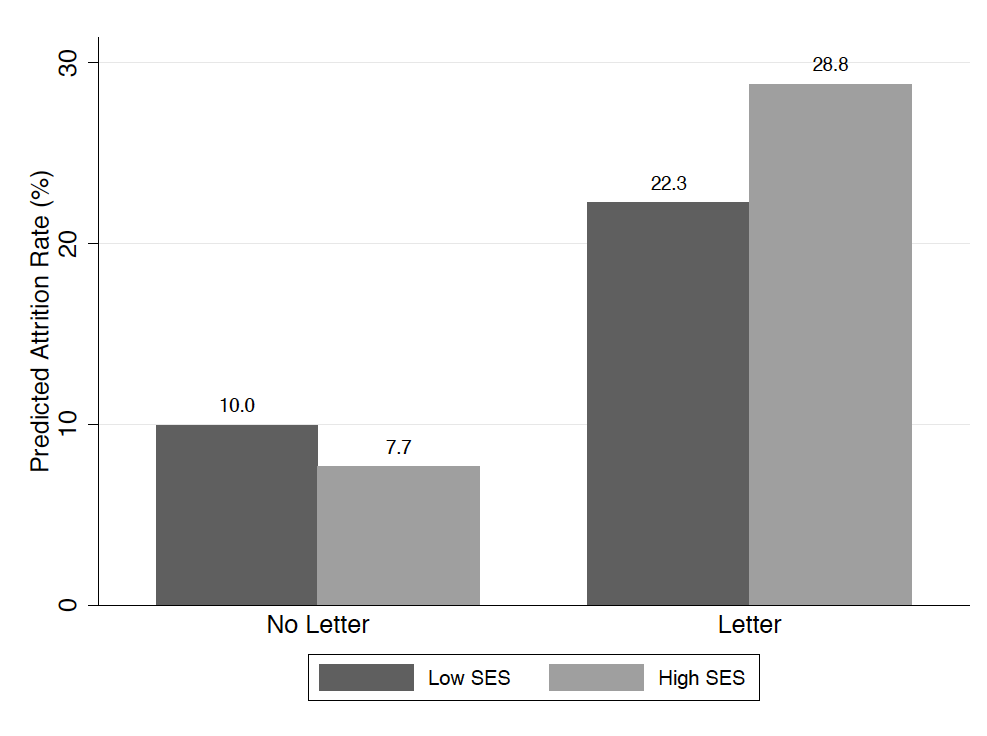

No. In fact, only 36.8 per cent of consumers ended the subscription when they had to take action to do so. In addition, sending those complex letters to the firm’s customers and requiring them to cancel actively was less effective at protecting consumers from low socioeconomic status (SES) neighbourhoods. Without letters, consumers living in low SES neighbourhoods were about 2.3 percentage points more likely to cancel, a 30 per cent difference compared to consumers in high SES neighbourhoods. In the responses to the letters that notified consumers that their subscriptions would continue unless they cancelled, however, this relationship reverses: we estimate a consumer in a high SES neighbourhood was 6.5 percentage points more likely to cancel than a consumer residing in a low SES neighbourhood. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Attrition rate with and without a letter

Although the population studied may not be perfectly representative of the broader population, our study provides simple, direct evidence that bad defaults can cause a large number of consumers to make costly errors. In addition, it suggests smart policy design—like setting the correct default—can have bigger benefits for low SES consumers than high SES consumers. Knowing how to design psychologically informed policies can help government agencies better protect everyone from exploitation, but especially those people who are least equipped to protect themselves.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ research: Letzler, Sandler, Jaroszewicz, Knowles, and Olson, “Knowing When to Quit: Default Choices, Demographics and Fraud,” Economic Journal, Vol. 127, Issue 607, December 2017.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Scam, by geralt, under a CC0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Ania Jaroszewicz is a PhD candidate at Carnegie Mellon University. Her research applies tools from economics and psychology to examine consumers’ financial decision-making. She is a 2016 Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow.

Ania Jaroszewicz is a PhD candidate at Carnegie Mellon University. Her research applies tools from economics and psychology to examine consumers’ financial decision-making. She is a 2016 Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow.