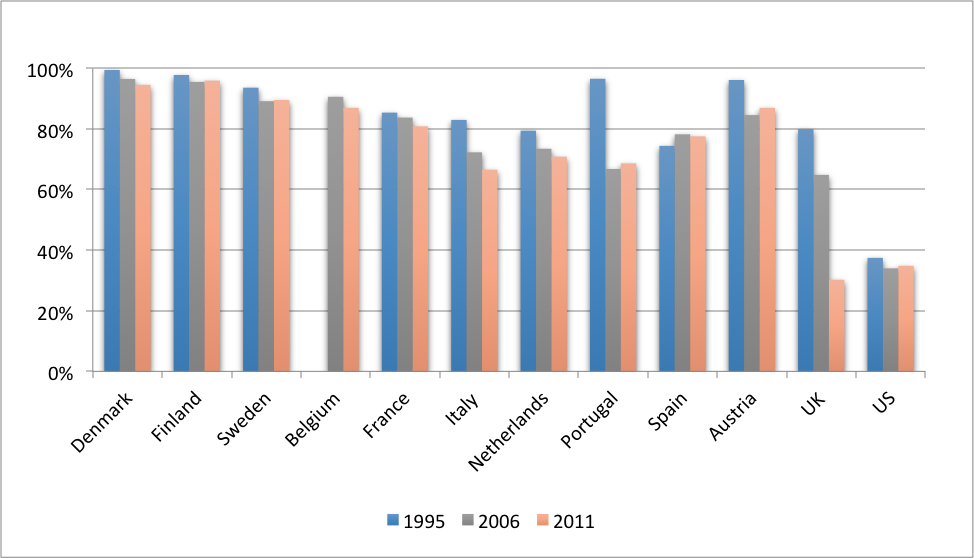

Over the last two decades, the financing of higher education in England has been transformed. The system has gone from one that offered free-of-charge, full-time undergraduate studies to being one of the most expensive in the OECD. The amount of direct public expenditure on higher education has been reduced from 80 per cent to around 25 per cent (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of higher education costs covered by public expenditure

Notes: The graph shows the trends in the share of higher education costs, covered by public expenditure across different countries. Source: OECD Indicators, 2013, 2014, 2015

But the reforms were not straightforward. While – through three main reforms in 1998, 2006 and 2012 – tuition fees increased from zero to around £9,000 per year today, means-tested financial support also increased – which for some students meant a reduction in financing constraints to attend university. Moreover, the development of the student loan system meant that for many education was still ‘free’ at the time of entry and re-payable after earnings reached a certain threshold.

Despite the extent of these reforms, there is surprisingly little research that can shed light on their consequences. Our study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the educational and labour market consequences of these higher education reforms, focusing on their socio-economic distributional effects.

Until 1998, (full-time) undergraduate education in public universities in England was free of charge to students. But in response to the declining quality of university education and rising costs, the government reformed the funding of higher education. The initial reform introduced in 1998 was later updated in 2006 and 2012. The reforms had three components:

- First, the introduction of tuition fees – initially means-tested at £1,000 per year, increasing to £3,000 per year in 2006 for all students and then eventually to £9,000 in 2012.

- Second, the introduction of a loan system that allowed students to borrow (annually) up to the fee amount.

- Finally, support to low-income students, including means-tested grants of up to £3,700 per year and means-tested loans of up to £5,000 per year.

Together these reforms aimed to shift the burden of higher education funding from the taxpayer to the beneficiaries – the students themselves.

Our research uses detailed longitudinal micro-data on all students in state schools in England (around 95 per cent) to evaluate the short- and long-run effects of the 2006 reform and the short-run effects of the 2012 reform. Following several cohorts of young people from school, we can link the data to those entering university and then, eventually – for a sizeable subset of students – track them into the labour market.

We then analyse the impact on enrolment, as well as the effects on a number of other margins. For example, the reforms may have implications related to how students sort in higher education through the choice of institution, its location and programme of study, as well as behaviour when in university – such as dropout, repetition of years and programme switching.

Finally, we link the impact of the reforms to students’ labour market outcomes, including their employment status, type of contract and earnings.

From a simple theoretical point of view, the predicted effects of higher education reforms on university participation and other outcomes are not entirely clear. For higher socio-economic groups, the absence of means-tested support suggests that there is an unambiguous increase in the cost of education.

But for medium and lower socio-economic groups, there is an ambiguous effect. Although all students were obliged to pay tuition fees, there was progressivity in upfront costs through increases in means-tested grants. Moreover, there was a release in financing constraints with access to additional loans and protection against personal bankruptcy due to student loans.

Overall, we find only very modest effects of reforms on students at both the ‘intensive’ and ‘extensive’ margins. Regarding the extensive – participation – margin, we find a reduction in the participation gap among those entering university from higher and lower socio-economic groups. There is a small decrease in participation (less than 1 per cent) in response to the reforms following the 2006 change in financing higher education and no significant effect of the 2012 change.

Moreover, the modest reductions are only present at the top of the income distribution, while the participation effect on students from medium and lower socio-economic groups is neutral or even slightly positive.

On the other outcomes, we continue to see only small effects. There is a reduction in the distance travelled, suggesting that students seem to compensate for increased tuition costs by reducing costs on other dimensions. Although students from less wealthy households are generally more likely to attend university closer to home, following the reforms they are actually more likely to move a little further away.

The effect on university choice and performance within university is quite mixed – improved completion rates among all students but also increased dropout rates for those from lower socio-economic backgrounds.

Finally, we observe marginally improved labour outcomes – in terms of employment status, type of contract and earnings – for those from higher-income households and marginally worse for those from lower-income households. These negative effects may point towards a differential sorting response into university by those from different wealth backgrounds. But again, all effects are economically small.

One key question is whether these reforms are cost effective in the longer run. Higher education is a risky investment and the loans to which students in England have access include some insurance. In particular, graduates repay tuition fees only once they have attained a predetermined income threshold. With respect to the 2006 and 2012 reforms, these stood at a threshold of around £15,000 and £21,000, respectively.

Moreover, any remaining debt would be written-off after 30 years. This suggests that some graduates will never be able to repay their loan in full. Although it is still too early to estimate the repayment rates for those affected by the 2012 reform, studies have projected that, under the 2012 regime, 73 per cent of graduates will not repay their debt in full within the repayment period, compared with only 32 per cent under the 2006 regime (Crawford and Jin, 2014).

Despite the potential repayment issue, a return to free higher education does not seem optimal with respect to equity. In fact, free higher education is likely to be regressive since more than 50 per cent of young people do not go to university, and those who do are disproportionately from high-income households.

In the absence of a graduate tax (in the form of deferred repayments) or income-contingent loans, higher education is typically absorbed into general taxation. An important next step would be to understand if, and by how much, the change in the tax system redistributes from lower to higher income individuals.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper Higher Education Funding Reforms: A Comprehensive Analysis of Educational and Labour Market Outcomes in England, LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) Discussion Paper No 1529

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Corey Seeman, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Ghazala Azmat is a Professor of Economics at the department of Economics in Sciences Po, Paris and a Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (LSE). Her main research interests are in applied and empirical microeconomics. In particular, her research focuses on topics in labour, education and public economics.

Ghazala Azmat is a Professor of Economics at the department of Economics in Sciences Po, Paris and a Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance (LSE). Her main research interests are in applied and empirical microeconomics. In particular, her research focuses on topics in labour, education and public economics.

Stefania Simion is a Senior Teaching Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and a Research Assistant at the Centre for Economic Performance (LSE). She received her PhD in Economics from Queen Mary University of London in 2017. Stefania’s research field is applied microeconomics, with a focus on economics of education and labour economics

Stefania Simion is a Senior Teaching Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and a Research Assistant at the Centre for Economic Performance (LSE). She received her PhD in Economics from Queen Mary University of London in 2017. Stefania’s research field is applied microeconomics, with a focus on economics of education and labour economics

Very interesting. But as the headline says this about the U.K., please compare the outcomes in Scotland, which has free tuition fees and a different system for financial support.