Female labour force participation has increased in most European countries in the last decades: the activity rate in EU15 has constantly increased in the last 20 years, gaining more than 10 percentage points (from 56 to 68 per cent). Nonetheless, the gender earnings gap remains substantially high in most countries.

Recent research highlighted that parenthood is one of the main factors behind the persistent gender gaps in the labour market. As the relevance of other competing factors (educational level, participation in the labour market, sector and occupational segregation) decreased, the birth of a child keeps affecting extremely unequally men and women (see Kleve et al., 2018 on Denmark and Angelov et al., 2016 on Sweden).

Among European countries, Italy is a particularly bad performer: while the employment rate of single women is in line with the European average, maternal employment is the lowest, before Greece.

In my research, I use newly available administrative data covering the universe of dependent workers in the private sector to estimate the impact of childbirth on maternal labour supply and earnings. Moreover, I exploit the introduction of a childcare subsidy conditional on giving up optional parental leave to assess the impact of shorter career breaks on labour market outcomes. The length of a career break after childbirth, in fact, may be a possible reason behind the negative labour market outcomes of new mothers: the loss of labour market experience and human capital depreciation would make it harder and more costly for the woman to go back to her previous occupation and, once back, to catch up with her previous career trajectory. The longer the break, the harder the readjustment.

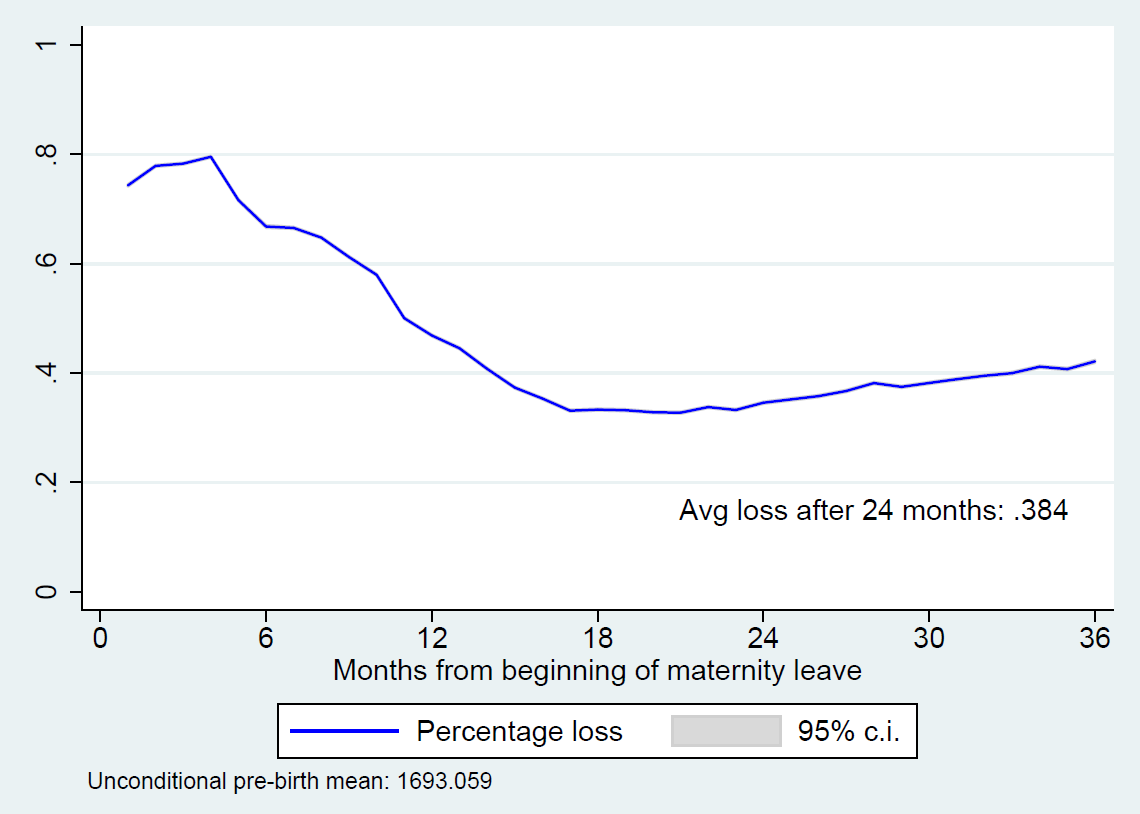

I find that women face a significant and dramatic loss in terms of earnings after the birth of a child; the loss is mainly driven by women leaving the labour market, but is also significant for those who go back to their previous employment. Taking shorter parental leave seems to have a positive effect only in the short run. Figure 1a shows the percentage loss in earnings faced by the woman since the beginning of mandatory maternity leave. The estimates come from an event study analysis and are computed with respect to the earnings trajectory that the woman was following before pregnancy.

During the first five months, all women have to be on mandatory maternity leave, and the Social Security Institute covers the lost salary with an allowance equal to 80 per cent of previous salary; the loss observed in the first part of the graph is thus mechanical. After the first five months, though, the woman can choose whether to ask for optional parental leave (for at most 6 months, covered by the Social Security Institute with an allowance equal to 30 per cent of previous salary), or to go back into employment. Right after mandatory maternity leave, roughly one third of Italian women who do not leave the labour market choose to use their entire parental leave entitlement, thus staying away from the labour market for almost one year, and one third choose to go back to work.

The Figure reflects this slow return to employment, showing that it takes almost one year and a half from the beginning of mandatory maternity leave for earnings to reach a stable path again; nonetheless, when they stabilize, earnings are at a much lower level than they would be in absence of the child. This loss amounts to almost 40 per cent; if we only focus on women who go back to work, excluding women leaving the labour market after motherhood, this estimate reduces, but stays significant.

Figure 1a. Percentage loss in earnings faced by the woman since the beginning of mandatory maternity leave

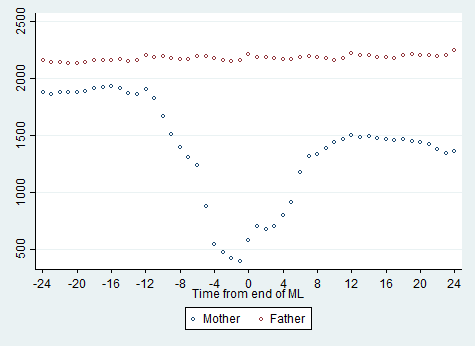

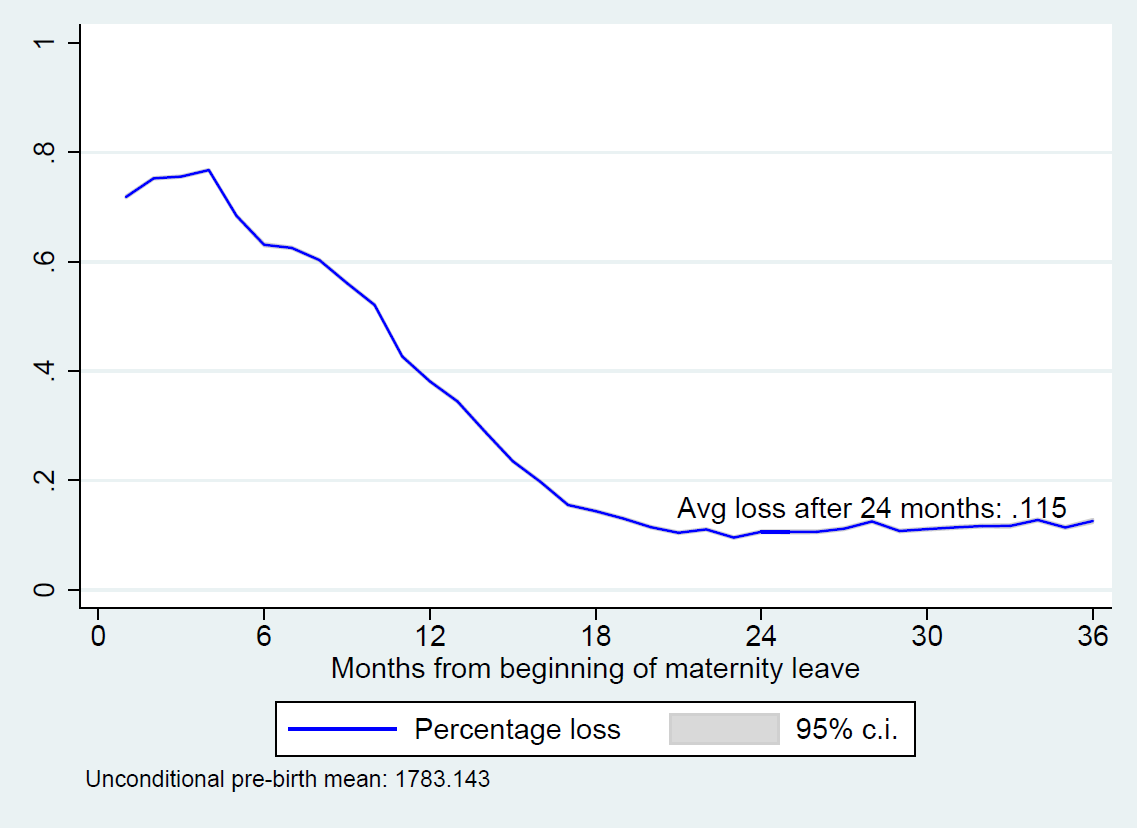

As shown in Figure 1b, the loss in conditional earnings (such as overtime and productivity premia) is around 11 per cent. That includes a proportion of women switching from full-time to part-time occupation, a decrease in the probability of working overtime and receiving productivity premia. This negative impact does not reduce over time and stays constant up to five years after childbirth. Modelling the earnings of fathers and mothers around childbirth shows that paternal earnings are unaffected by the event, that hence widens the within-couple gap in a permanent way (see Figure 2).

Figure 1b. Loss in conditional earnings (such as overtime and productivity premia)

Figure 2. Earnings of fathers and mothers around childbirth

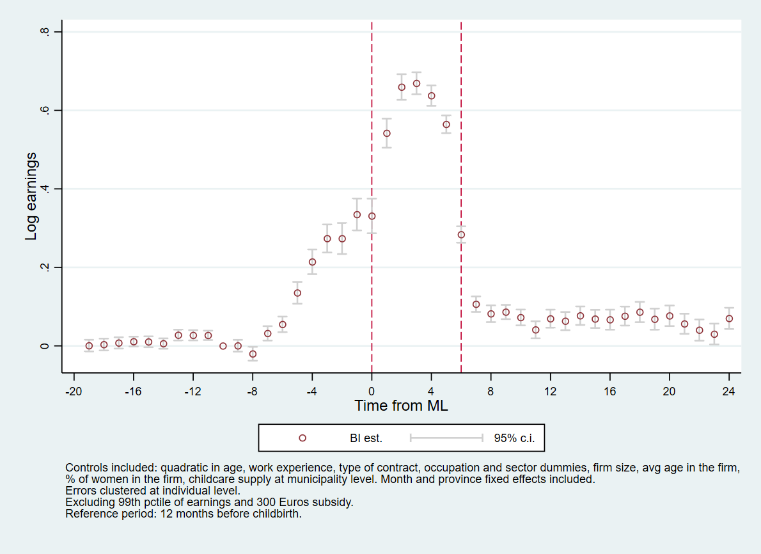

The introduction of the Bonus Infanzia, a monthly childcare subsidy granted per each month of optional parental leave that the woman gives up, allows to explore whether the huge loss just detected can be reduced by reducing the length of the career break after childbirth.

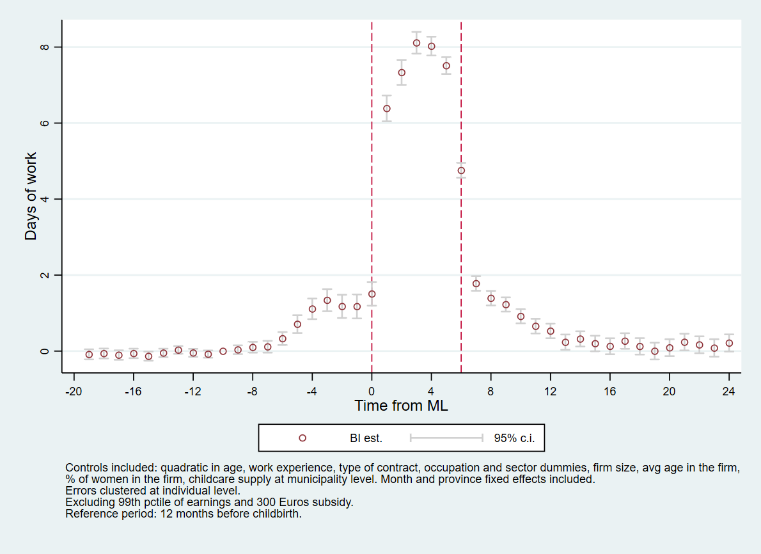

The answer seems to be negative. I compared the trends in earnings before and after childbirth for women who used and women who did not use the Bonus. As shown in Figure 3a, women who used the subsidy, and thus took on average 4 months of parental leave less than the other group, experience a premium in earnings only right after the end of mandatory maternity leave, when the second group of women is (mostly) on leave. As soon as the time window when most women use their optional leave expires (roughly six months after the end of mandatory maternity leave), so does the Bonus premium: one year after childbirth, there is no significant difference in the earnings of the two groups of women. The same applies when looking at the labour supply at the intensive margin: conditional on going back to work, the difference in the number of days worked in a month is significant only in the first six months after the end of maternity leave, while it disappears shortly after (see Figure 3b).

Results are confirmed in an instrumental variables analysis, using eligibility and heterogeneity in childcare facilities availability as exogenous variables. Nonetheless, women who used the Bonus are less likely to leave the labour market: one year after childbirth, only 7 per cent of them left employment, while 22 per cent of women who did not use the Bonus did.

Early childcare supply in Italy is low and heterogeneously distributed; shortage in the supply of public infant toddler centres forces reliance on private supply, which has higher costs and more heterogeneous quality standards. Most working families have to rely on grandparents, family network and informal arrangements to reconcile work and care responsibilities. Moreover, research already showed that formal childcare has beneficial effects on the cognitive and non cognitive development of children.

Thus, subsidies to families who rely on formal childcare can be beneficial to households and children’s welfare. Nonetheless, binding them to a reduction in the length of parental leave does not seem to provide any additional benefit in terms of maternal labour market prospects.

Figure 3a. Log earnings

Figure 3b. Days of work

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the author’s paper The Labour Cost of Motherhood: Is a Shorter Leave Helpful?presented at the Royal Economic Society’s annual conference at the University of Sussex in Brighton in March 2018

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Window shopping, by Antoine K, under a CC-BY-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Erica Maria Martino is a postdoctoral researcher at Institut National d’études Démographiques (INED), Paris.

Erica Maria Martino is a postdoctoral researcher at Institut National d’études Démographiques (INED), Paris.