Monetary policy has been unprecedentedly very accommodating in the post-global financial crisis (GFC) era, particularly in the developed economies. In the last few years, there has been a debate about the rolling back of some of the actions taken in the wake of the crisis, for which different terms and jargons have been invented, e.g. “exit-strategy” and/or “normalisation” of monetary policy. One crucial factor that led monetary policymakers to defer the normalisation (if that exists) has been the modest level of price pressure in recent years.

In addition to the deferment of contractionary or normalisation measures, the sanguine outlook for inflation kept the hawkish voices quiet. However, in the last couple of years, and particularly since Brexit, inflation in the UK has started to pick up rather more swiftly than in any period since the GFC. This then reignited the debate on winding up the stimulative stance that has been taken hitherto. The additional stimulus taken after Brexit, with the Bank of England dropping the bank rate by 25 basis points in August 2016, was withdrawn in November 2017. According to the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voting history, in the March and May 2018 meetings, some members suggested further tightening of the monetary stance.

In this regard, LSE’s Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) conducted a survey in which a two-thirds majority of respondents suggested that the MPC should not raise the interest rate due to the uncertainty and weak real wage growth. While this suggestion has logical and empirical merits, the context in which it has been made is worth paying attention to. While most of the economists surveyed argued that weak wage growth and labour market outlook were reasons to hold the interest rate, there is also no consensus whether the labour market is a good indicator of inflationary pressures.

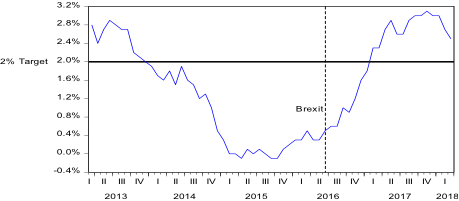

A corollary to the above, the most important aspect for the Bank of England and other stakeholders interested in recent UK inflation dynamics is to consider the context and history of the recent behaviour of inflation and its contributory factors. As clearly indicated in Figure 1, it was not inflation but risk of deflation that had occupied the monetary policy debate in recent years and in the run-up to Brexit.

Figure 1. Consumer Price Index, March 2013 – March 2018; Source: Office for National Statistics (2018)

Brexit, one of the most crucial events in recent British history, has led to an increased level of uncertainty weighing upon the real economy. In that uncertain environment, one certainty was the falling pound. Even though there is a consensus among academics and policymakers that currency depreciation has significant positive effects on inflation, i.e. exchange rate pass-through, post-Brexit inflation forecasts did not take this important channel into account and concomitantly made projections that were nowhere close to actual inflation when the effects of depreciation materialised. For those who took this factor into account, it was clear that the sharp depreciation associated with Brexit would lead to reversion of inflation to and through the target and improvements in the balance of payment. It turned out that they were right!

In response to the question ‘shall the Bank of England raise rates or stay put?’, we need to understand the context of UK inflation dynamics. While the CFM survey is interesting and has focused on an important relationship, i.e., labour market – inflation (often called the Phillips curve), it is important to consider that the labour market outlook is only one factor that may influence inflation. There are many other equally important factors that shall also be taken into account when contemplating inflation outlook and optimal policy response. These may also include the outlook for economic growth, inflation expectation, exchange rate dynamics and cost shocks. While the evidence on inflation expectations suggests that they are well anchored and commodity prices are not historically very high (including the largest traded commodity, i.e., oil), there is no reason to expect that, other things being equal, there will be inflation pressure coming from these channels.

The exchange rate is, in fact, the biggest culprit (or hero, if you think it brought inflation back to the target) in increasing the inflation rate, but there are two reasons why one should not be worried about it. First, the past increases in inflation due to a weaker sterling will drop out of current estimations, as the inflation measure, i.e., the CPI, is calculated year on year. Second, and most importantly, there has been a gradual increase in the value of sterling in the last few months, and that implies that there will be an opposite effect this time, which may put a drag on the rate of inflation. A clear manifestation of these two factors is evident in the fall in the inflation rate in the last quarter (Fig 1).

Undoubtedly, the increase in inflation in the post-Brexit era has diminished the increases in the real wages of British households. However, increasing interest rates at this stage will certainly have a further negative impact on household income through an increase in interest payments. Perhaps, in an uncertain environment, “decision deferral” is considered the best strategy. Therefore, a cogent strategy for the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street is to not throw the baby out with the bathwater, while inflation is already on the downward trajectory, the Bank may stand its ground!

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by PeterRoe, under a CC0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Muhammad Ali Nasir is senior lecturer in economics at Leeds Beckett University’s department of economics, analytics and international business.

Muhammad Ali Nasir is senior lecturer in economics at Leeds Beckett University’s department of economics, analytics and international business.