On average, women still earn less money than men in most developed countries around the world according to the OECD. In the US and UK, for example, women are paid between 82 and 85 cents for every dollar a man earns. As a potential remedy to this issue, many legislators and organisations have begun to adopt pay transparency policies. A new UK law taking effect in April 2018 requires companies with at least 250 employees to publicly disclose gender wage gap information. Going a step further toward pay transparency, Germany now allows individuals in companies with at least 200 employees to obtain median salaries for at least six comparable coworkers.

A 2018 report of pay transparency policies in 526 Swiss organisations found that approximately 40 per cent already implement a similar policy that discloses aggregated pay information, while 30 per cent disclose individual information about employees’ base pay and pay raises. Alexandra Arnold (University of Lucerne), coauthor of this report, notes that “overall, there is a trend toward more transparency: over the last two years about 15 per cent of the organisations increased pay outcome transparency while only a few organisations decreased pay transparency.”

Exchanging pay information, however, remains taboo in the workplace across many cultures. In fact, one survey in the UK found that people were seven times more likely to refuse disclosing their salary than their intimate sexual history to a stranger. Little research, however, explicitly examines the widespread conventional wisdom that people are typically reluctant to share pay information.

This knowledge is crucial to business leaders seeking to effectively manage pay communication policies because it provides some guidance on how employees will likely react to these recent policy changes.

Our research of over 400 adults employed in various industries sought out answers to two important questions.

- First, what do employees typically prefer when it comes to pay transparency policies?

- Second, how do employee preferences and the policies under which they work interact to shape important job attitudes? That is, how does alignment or misalignment between preferences and experienced policy impact employees?

Before exploring employee attitudes toward pay secrecy, we must first differentiate two different types of policies.

Pay disclosure policies deal with the extent to which organisations share employee pay information. For example, Whole Foods shares individual employee wage and salary information, while other organisations share more generalised information such as salary bands or median pay. Employees who prefer transparent disclosure policies would agree with the statement from our scale: “I believe organisations should have to disclose how much they pay their employees”.

Employee communication policies, on the other hand, regulate the extent to which individuals are able to share pay information with one another. For example, approximately 50 per cent of organisations in the U.S. prohibit employees from discussing pay despite the fact that these policies are illegal under the National Labor Relations Act. Employees who prefer transparent communication policies would agree with the statement from our scale: “Organisations should allow employees to discuss their pay with one another”.

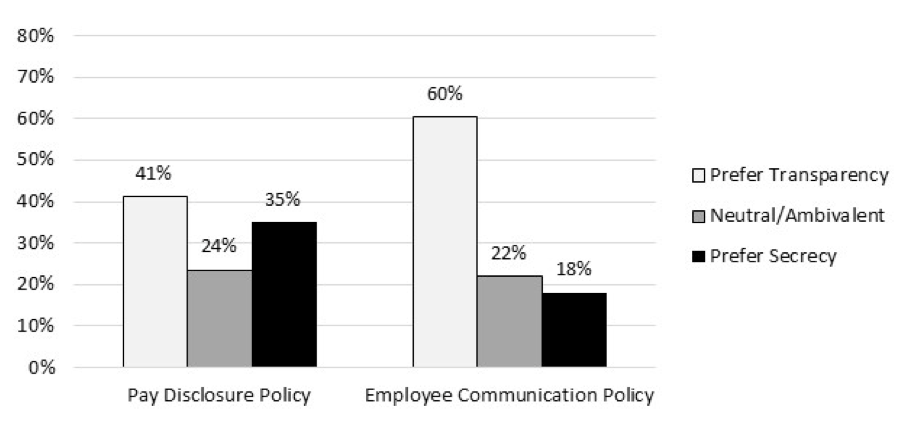

The graph below summarises the proportion of employees in our diverse sample who reported preferences for these two types of policy. On the left, we see that employee opinion is decidedly mixed when it comes to organisations disclosing pay information. While 41 per cent reported they preferred transparent organisational disclosures, 35 per cent reported they preferred for pay information to be kept confidential. These findings should prompt organisational leaders to consider pay transparency regulations in a new light. Perhaps a third of employees may be opposed to such policies, which could create challenges for organisations adapting to these new laws.

Figure 1. Pay secrecy preferences

On the right, we see a different trend. The majority of employees (60 per cent) preferred transparent employee communication policies, meaning they were opposed to rules that prohibit pay discussions among coworkers. These stark differences are likely due to the fact that employees retain far more control over how they collect and share pay information when employee communication policies are more permissive. It is probably very common for a given employee to be willing to exchange pay information will certain coworkers, but not others.

The second question we examined was: How does alignment or misalignment between preferences and experienced policy impact employees?

Again, we examined this question separately for the two forms of policy. With regard to pay disclosure policies, alignment between employee preferences and policies were associated with marked increases in both job satisfaction, as well as fairness perceptions of the organisation. Stated differently, regardless of whether the organisation utilised a secretive or transparent disclosure policy, employees reported greater satisfaction and fairness when the policy matched their preferences. This perhaps runs counter to the widespread assumption that greater transparency will be perceived as fairer among employees.

With regard to employee communication policies, we observed a different trend. In this case, secretive policies that prohibit pay conversations yielded no benefits for employee job satisfaction or fairness perceptions. In fact, employees with transparent communication preferences exhibited reduced satisfaction and fairness perceptions when working in organisations with secretive policies. Thus, there appears to be an asymmetry in this case, and importantly, secretive communication policies do not seem to yield benefits at least in terms of employee relations.

Overall, employee attitudes toward pay transparency are very mixed, especially with regard to organisations disclosing pay information. Furthermore, these attitudes are associated with job satisfaction, and even how fair they perceive their employers.

Pay transparency is a thorny issue that poses challenging questions to both organisations and society more broadly. It is important to note that pay transparency is not a binary decision. Although more research is needed to make substantive recommendations, we will highlight the option to offer blended pay information policies. Similar to what is now required by law in Germany, a blended policy would offer employees aggregated pay information in the form of salary bands or medians which can help identify and remedy inequalities through greater transparency, while simultaneously preserving personal privacy by keeping individual pay levels confidential.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper The role of pay secrecy policies and employee secrecy preferences in shaping job attitudes, Human Resource Management Journal

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Christian Dubovan on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Brandon W Smit is assistant professor of business administration at Indiana University East, USA. He earned his PhD in industrial and organisational psychology from Saint Louis University. His research focuses on work–family conflict, psychological detachment and pay secrecy and has been published in top academic journals, as well as covered by the popular press.

Brandon W Smit is assistant professor of business administration at Indiana University East, USA. He earned his PhD in industrial and organisational psychology from Saint Louis University. His research focuses on work–family conflict, psychological detachment and pay secrecy and has been published in top academic journals, as well as covered by the popular press.

Tamara Montag-Smit is assistant professor of management at Ball State University, USA. She conducts research on workplace creativity, compensation, workplace mentoring and work–life. Her research has been published in leading academic journals.

Tamara Montag-Smit is assistant professor of management at Ball State University, USA. She conducts research on workplace creativity, compensation, workplace mentoring and work–life. Her research has been published in leading academic journals.