Zambia’s quest for a support facility from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been put on hold as the sceptre of external debt distress hangs over the economy. Coming on the back of the Republic of Congo’s default on a $ 478 million payment in June 2016 and Mozambique’s default on a $ 60 million payment in January 2017, it sends a signal that the IMF has pricked its antennae for lurking debt distress risk in sub-Saharan Africa.

The move fits like a glove into the memory of the mid-1990s Bretton Woods-led High Indebted Poor Countries Initiative, whose core mandate was staving off the risk of low-income economies being saddled with unsustainable debt. It is almost as if sub-Saharan Africa’s halcyon days, during which economies issued Eurobonds in an almost competitive fashion, have stayed behind. Economies are beginning to buckle under the pressure of external debt. The punitive path of debt restructuring, with creditors taking a haircut, is one the region is becoming all too familiar with.

The case of Zambia is of particular interest. The economy has not defaulted on its payment, but debt distress by definition refers to the evidence that a country’s inability to service its debt obligation has either materialised or is imminent. A cursory look across key external debt sustainability indicators suggests that Zambia’s position is mirrored across some peer lower middle-income economies (those economies whose gross national income per capital lies between $ 1,006 and $ 3,955) and perhaps begs a reality check.

To check the external debt sustainability status of an economy, one typically looks at a set of ratios whose core business is to show the degree to which the debt burden is sustainable in the long-term. The evolution of key features in the structure of debt show whether the terms are, by and large, improving or deteriorating over time. Key ratios include the stock of public and publicly guaranteed debt to exports; the stock of public and publicly guaranteed debt to tax revenue and the debt service to exports. Key features in the structure of debt are changes in the average maturity period; changes in the grace period and the trend in the average interest rate of new debt commitments.

The legacy of the commodity price rout

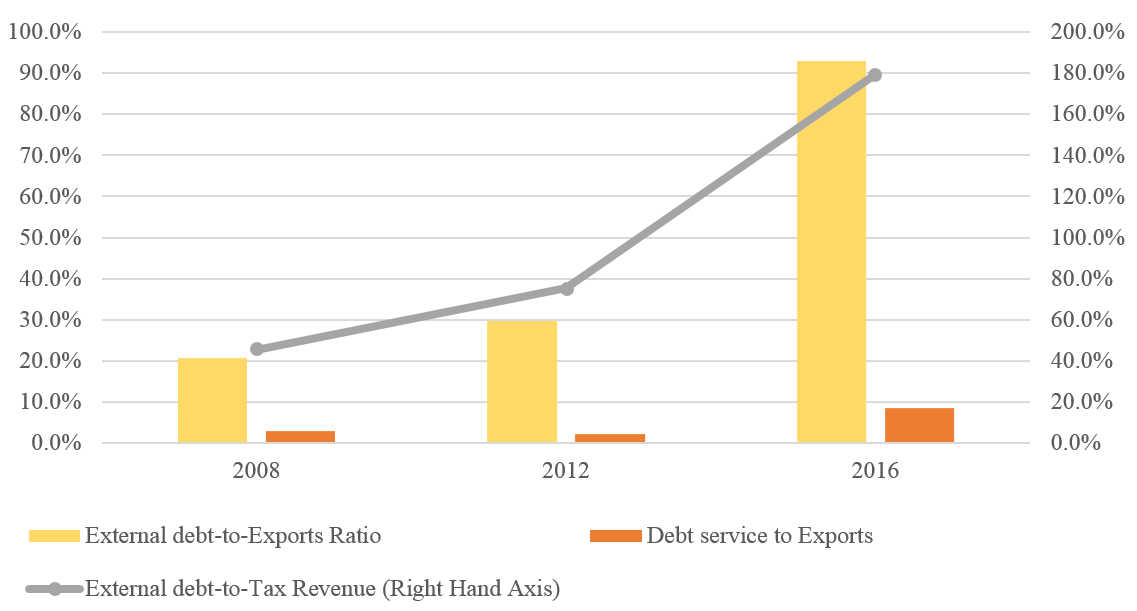

Zambia’s slide into external debt woes comes as a stark pointer to the dreadful mess precipitated by the downturn in commodity prices and a debt binge in a number of economies. The period between 2014 and 2016 was characterised by considerable deterioration in the country’s key ratios. In 2016, the price of copper (which accounted for 80 per cent of the country’s export revenue) tanked by 54.6 per cent to $ 4,471 per metric tonne from the 2010 peak.

In a bid to address the worsening fiscal deficit, the country issued two of its three Eurobonds in this period, mobilising $ 1 billion in 2014 and $ 1.25 billion in 2015, piling up more foreign currency-denominated debt even as depressed export revenue and a broadly adverse macroeconomic environment suggested the economy was skating on thin ice with regard to its external debt sustainability.

The deterioration of key ratios in Zambia’s external debt between 2008 and 2016 was amplified by underlying changes in the structure of new debt. For instance, data from the World Bank show that the maturity period of new commitments declined from 42.9 years in 2008 to 16.3 years in 2016. This suggests that over this period, the country’s stock of public and publicly guaranteed external debt has been increasingly exposed to rising refinancing risk, the risk that a country will be unable to secure new financing in view of maturity existing debt. Further to this, by the end of 2016, Zambia’s external debt accounted for 68.3 per cent of its total debt, a skew that exposes the economy to foreign exchange risk especially in an environment where the local currency has been rattled by subdued commodity prices.

Figure 1. Zambia’s public external debt ratios

Source: World Bank

External debt distress is poised to rear its head again

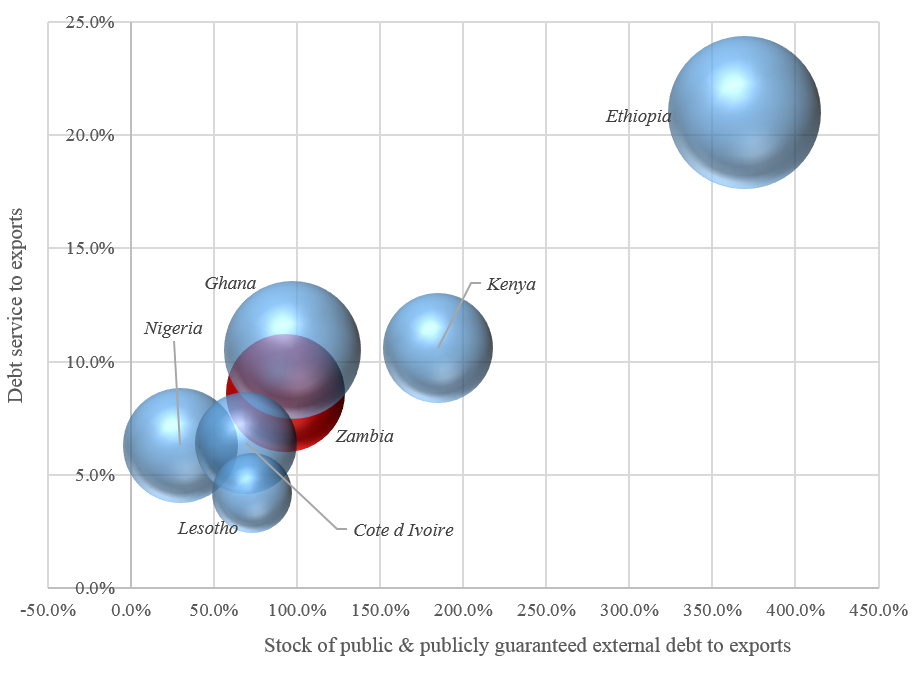

Even as Zambia adopts measures aimed at mitigating pressures from vulnerability to external debt distress, notably trimming the fiscal deficit to 4 per cent of GDP, it is evident that a number of the red flags that were discernible in the build-up to the present state are visible in other peer economies. Amongst lower middle-income economies (economies with a gross national income per capita that ranges between $ 996 and $ 3,895), for example, Ghana performs worse than Zambia on all three key ratios (the stock of public and publicly guaranteed debt to exports; the stock of public and publicly guaranteed debt to tax revenue and the debt service to exports).

Granted, external debt accounts for a smaller proportion of the country’s debt load, at 53.2 per cent compared to Zambia’s 68.3 per cent, but on key indicators such as external debt to exports and tax revenue, there is reason to believe that Ghana needs to slow-pedal its uptake of external debt in the coming years.

Similarly, whereas Kenya’s external debt to tax revenue is lower than that of Zambia, its external debt to exports and debt service to exports ratios are higher and call for a reality check. The goal here is not to imply that Zambia’s metrics provide a threshold for external debt sustainability but to point to the fact that characteristics that have defined the country’s external debt environment are mirrored across sub-Saharan Africa.

Amongst low-income economies (economies with a gross national income per capita that is below $ 995), all three ratios suggest that Ethiopia’s external debt position warrants deeper scrutiny. Already, the foreign currency crunch experienced in the country in the recent past has brought to visibility to the magnitude of external imbalances the economy is confronting and sends a signal on the headwinds of foreign exchange risk Ethiopia could run into.

Figure 2. Public external debt ratios

Source: World Bank

Note: The size of the bubble denotes the stock of public external debt to tax revenue

Seizing the Vronsky moment

Zambia’s position today calls to mind Leo Tolstoy’s literary masterpiece ─ Anna Karenina. In Chapter 19 of this work, the reader encounters the character Vronsky, who, following a change of fortune, has run into financial difficulties and realises his cash at hand is a paltry 15 per cent of near term debt obligations. Almost akin to IMF shelving talks for a possible support programme to Zambia, Vronsky is barred from seeking a bailout from his affluent mother. In this scheme of events, Vronsky classifies his debts based on urgency of payment, seeks a loan from a money lender, whose proceeds he uses to refinance, and more importantly, undertakes to lead a more frugal life through slashing expenses.

In similar fashion, it is time for sub-Saharan African economies to go beyond the almost consensus view of strengthening efforts to widen the tax base, so as to rake in more revenue, and couple it with much needed adherence to fiscal deficit pruning with a view to taming the rise in vulnerability to debt distress. As commodity prices gradually rebound from the 2014 – 2016 downturn, sub-Saharan Africa has an opportunity to transition from an era dominated by rapid growth to one of balanced and more stable growth. Sound fiscal management and debt sustainability are core pillars of this transition.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo of Lusaka, by Lighton Phiri, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Julians Amboko is a is a financial news correspondent with Nairobi based Nation Media Group, covering capital markets and macroeconomics. Previously he was senior research analyst with the financial advisory firm StratLink Africa Ltd, He has experience in Sub-Saharan Africa focused economic research and analysis covering East, West and Southern Africa. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Julians Amboko is a is a financial news correspondent with Nairobi based Nation Media Group, covering capital markets and macroeconomics. Previously he was senior research analyst with the financial advisory firm StratLink Africa Ltd, He has experience in Sub-Saharan Africa focused economic research and analysis covering East, West and Southern Africa. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Well penned and explained.

African countries need to ask themselves a lot of questions. Start by implementing austerity measures that will take our foreign debt to manageable levels. These austerity measures should be inclined towards reducing our spend and not increasing the tax on the already overburdened populace or widening the tax base by bringing in the widely untaxed informal sector. If this is not proactively handled then we’re headed in the direction of Greece. Again if we don’t take care a lot of African countries will find themselves where Zimbabwe currently is, companies buying foreign currency (USD) from the black market at a premium of more than 150%.

This is a call to action for African countries and leadership. Thanks Amboko.