National cultural imprints have a profound influence on entrepreneurship. Johannes Kleinhempel, Mariko Klasing and Sjoerd Beugelsdijk write that among second-generation immigrants, those whose parents come from countries with a strong entrepreneurial culture are more likely to become entrepreneurs.

National culture and entrepreneurship

Differences in entrepreneurial activity between countries are pronounced and persistent. So persistent, in fact, that over 90 per cent of the variation in present-day entrepreneurship across 155 countries are explained by entrepreneurship rates in the 1980s. What is driving these enduring differences?

For more than a century, scholars have argued that culture may be one of the deep-rooted determinants of entrepreneurship. For example, it has been argued that cultures characterised by risk-taking, achievement-oriented or independence-seeking values are conducive to entrepreneurship. However, empirical research has produced mixed and contradictory results, in part because it has been traditionally difficult to isolate the effect of culture on entrepreneurship from other country-specific determinants.

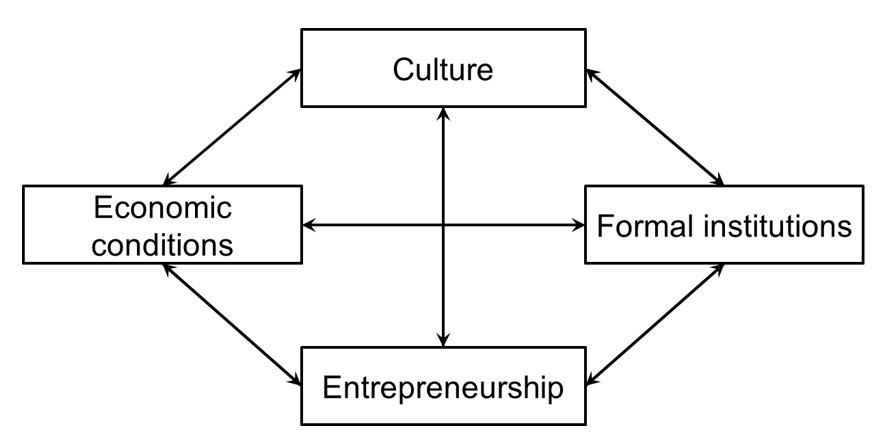

This difficulty arises because entrepreneurship and the economic, formal institutional, and cultural characteristics of countries are deeply intertwined and influence each other reciprocally (see Figure 1). Consequently, it is challenging to zoom in on the role of culture in entrepreneurship.

Figure 1. Entrepreneurship and the economic, formal institutional, and cultural characteristics of countries influence each other

Empirical context

In a recent study, we examine the entrepreneurial activity among second-generation immigrants of different ancestries to tackle this theoretical and empirical challenge. Second-generation immigrants were born, educated, and live in one country, but they were raised by parents who came from another country. This provides a useful empirical context. By virtue of living in the same country, second-generation immigrants share the same market and institutions; deal with the same bureaucrats, bankers and businesspeople; and are subject to the same rules, regulations, and red tape. This allows us to hold economic and formal institutional conditions constant and to overcome the circularity shown in Figure 1.

However, since culture is durable, portable, and intergenerationally transmitted, second-generation immigrants of different ancestries may differ in their propensity for entrepreneurship as they are partly influenced by the culture of their parent’s country of origin. Against this backdrop, when it comes to second-generation immigrants, those whose parents emigrated from countries with a strong culture of entrepreneurship are more likely to become entrepreneurs than those whose parents come from countries with a weak culture of entrepreneurship.

Analysis and findings

To test our hypothesis, we analysed data from two independent samples: 65,323 second-generation immigrants of 52 different ancestries in the United States and 4,165 second-generation immigrants of 31 ancestries in Europe. Using multilevel modelling, we found that the entrepreneurial culture of the country of ancestry is positively associated with the likelihood that second-generation immigrants engage in self-employment, both in the United States and Europe.

We also find that second-generation immigrants in the United States are more likely to be self-employed when their counterparts who were raised and live in Europe have a higher propensity for entrepreneurship—and vice versa. This further supports our hypothesis that culture influences entrepreneurship, since the only commonality between these two groups of people is their parents’ country of origin.

We also examine whether our results are robust to empirically accounting for a number of alternative non-cultural explanations proposed by entrepreneurship and immigrant entrepreneurship scholarship. For example, conditioning on discrimination, on financial resources, on skills, on family support, or on direct parent-child linkages does not change our main results.

Intergenerational cultural transmission

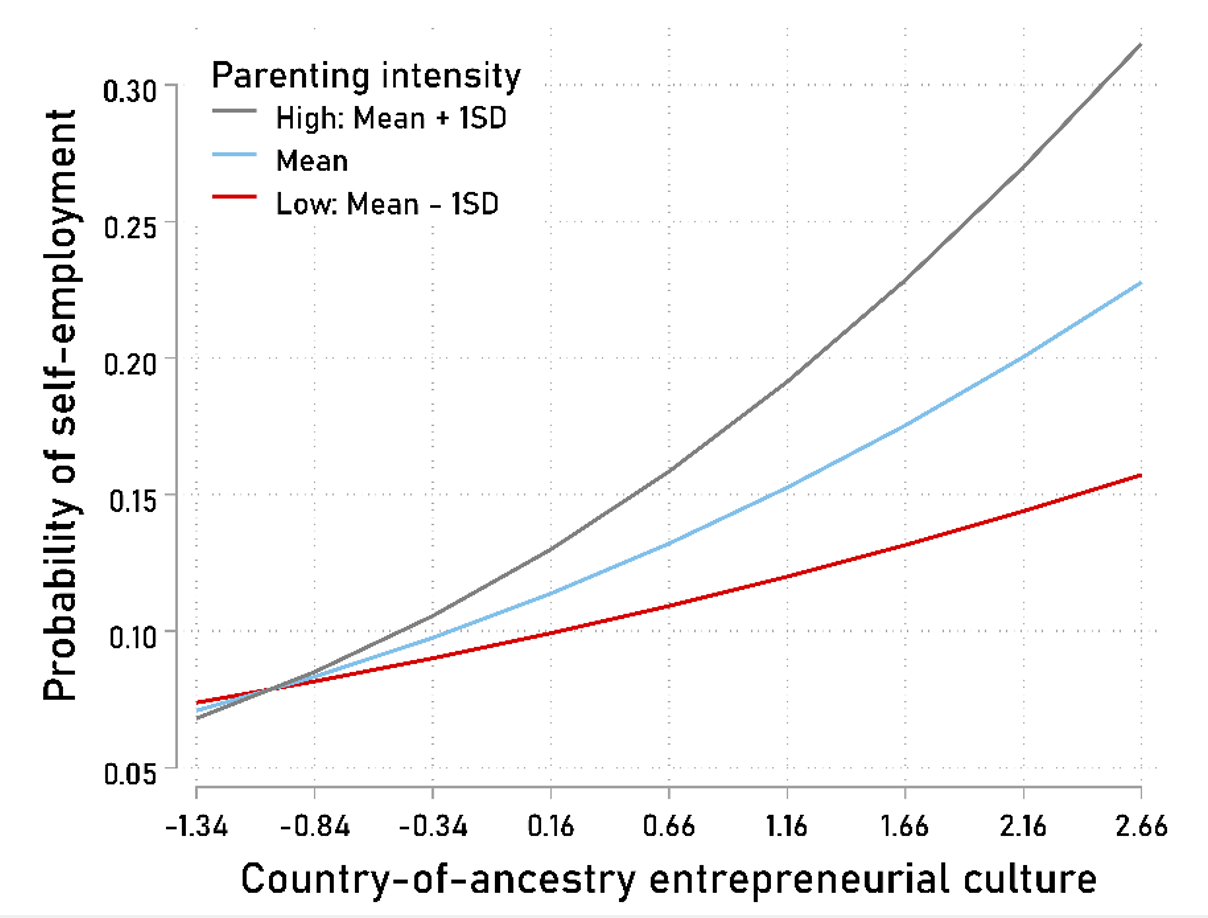

To further unpack this effect, we zoom in on the underlying key mechanism: intergenerational cultural transmission. We argue that more intense parent-child interactions should facilitate the transmission of cultural imprints from parents to children. We probe whether the intensity of parenting (the time parents spend with their children) strengthens the relationship between country-of-ancestry entrepreneurial culture and the likelihood that second-generation immigrants become entrepreneurs.

The results are visualised in Figure 2 and clearly indicate that parenting intensity strengthens (positively moderates) the relation between country-of-ancestry entrepreneurial culture and second-generation immigrant entrepreneurship.

Figure 2. Parenting intensity strengthens the country-of-ancestry effect on second-generation immigrant self-employment

Discussion

National culture is a deeply rooted driver of the observed pronounced and persistent differences in entrepreneurial activity across countries. These differences have implications for national economic performance, since entrepreneurship spurs innovation, job creation, and economic dynamism.

Our findings underline the need for policymakers to take the cultural context into account in designing entrepreneurship policies and promotion programmes. Typically, programmes to promote entrepreneurship have focused largely on improving economic and formal institutional conditions, such as better access to finance and less red tape. Less emphasis has been placed on informal institutions, such as culture. This makes sense. Policymakers can reduce red tape and open up funding schemes, but they cannot directly change cultural imprints. But this does not mean that we should ignore culture altogether. It is very likely that the effectiveness of entrepreneurship promotion programmes depends on prevailing cultural values and norms. A culturally sensitive approach to entrepreneurship promotion is warranted.

Summing up

National cultural imprints are durable, portable, and intergenerationally transmitted. They persist over at least two generations and in different economic and institutional contexts. Second-generation immigrants, who were born, raised, and educated in the same country, and who face the same economic and institutional circumstances, are more likely to be entrepreneurs if their parents come from countries with a strong rather than a weak entrepreneurial culture..

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Cultural Roots of Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Second-Generation Immigrants. Organization Science.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Ewan Buck on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy