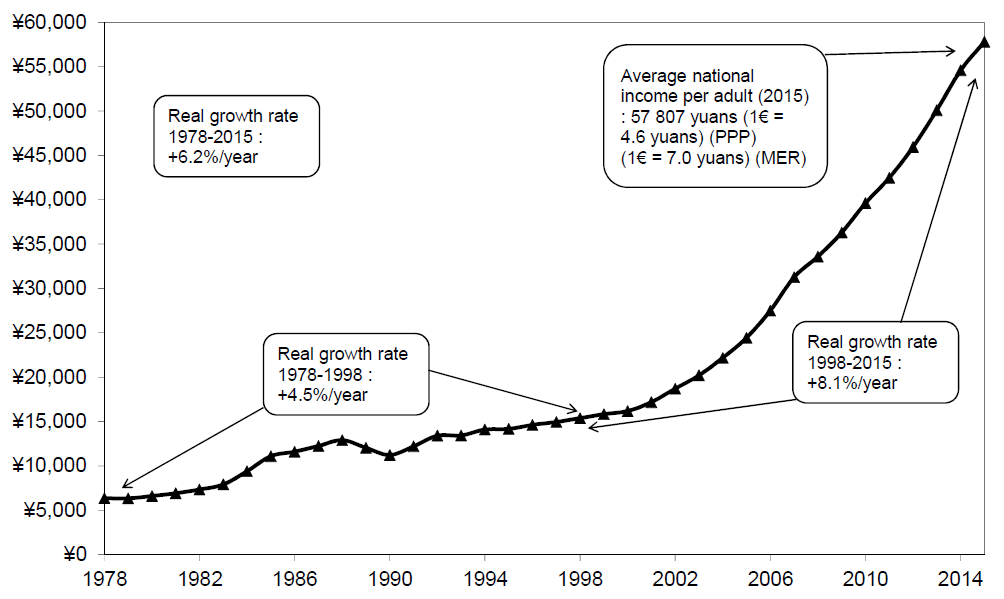

Between 1978 and 2015, China moved from a poor, underdeveloped country to the world’s leading emerging economy. Despite the decline in its share of world population, China’s share of world GDP increased from less than 3 per cent in 1978 to about 20 per cent by 2015 (see Figure 1). According to official statistics, real national income per adult grew more than eightfold between 1978 and 2015. While average national income per adult was approximately €120 per month in 1978 (expressed in 2015 euros), it exceeded €1000 per month in 2015 (see Figure 2). Annual per adult national income rose from less than 6500 yuans in 1978 to over 57800 yuans in 2015, i.e., from about 1400 euros in 1978 to about 12500 euros in 2015 — these amounts are expressed in 2015 yuans and euros using the latest purchasing power parity estimates.

Figure 1. China’s share in world population and GDP, 1978-2015

Figure 2. The rise of per adult real national income, 1978-2015 (2015 yuans)

Note: National income divided by adult population. National income = GDP – capital depreciation + net foreign income.

However, relatively little is known about how the distribution of income and wealth within China has changed over this critical period. That is, we do not have consistent estimates of the extent to which the different income and wealth groups have benefited (or not) from the enormous macroeconomic growth. The household surveys that are used to study distributional issues in China (e.g., Piketty and Qian, 2009) suffer from massive under-reporting, particularly at the top of the distribution, and are typically not consistent with the data sources that are used to measure macro growth (namely, national accounts). This is an issue of tremendous importance not only for China and its future development path, but also for the rest of the world and the social sustainability of globalisation.

Wealth accumulation (1978-2015)

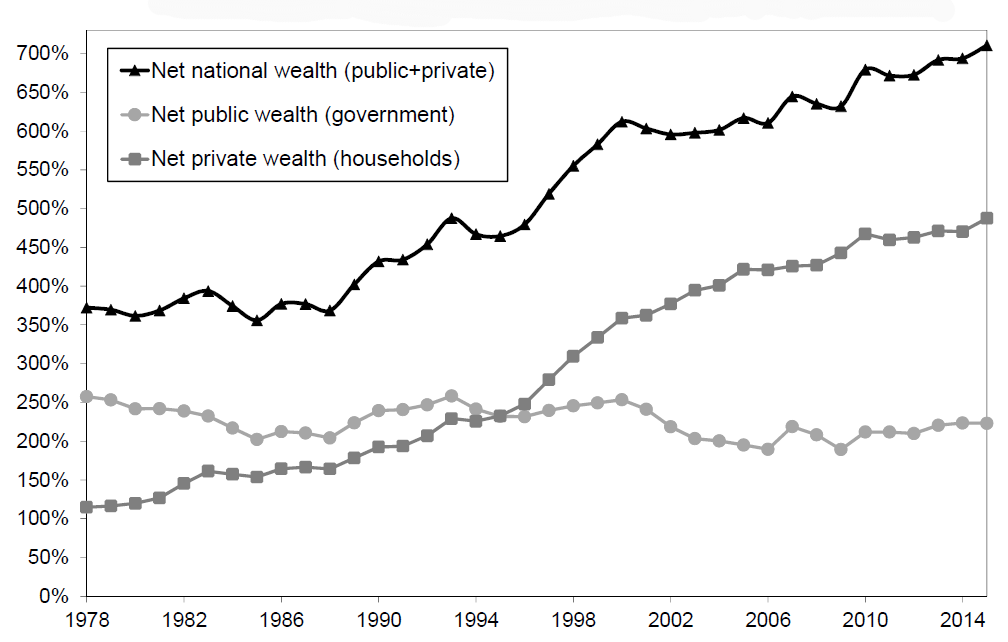

In the current research, we combine official and non-official sources (including independent estimates of China’s balance sheets) to provide the first systematic estimates of the level and structure of China’s national wealth since the beginning of the market reform process. (See, e.g., Li Yang et al, 2013a, 2013b, 2015; Ma et al, 2012; and Cao et al, 2012.) We find that the national wealth-income ratio has increased from 350 per cent in 1978 to 700 per cent in 2015. This increase is mainly driven by the increase of private wealth, which went from 115 per cent to 487 per cent of national income during the same period. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. Public vs private property in China 1978-2015 (% national income)

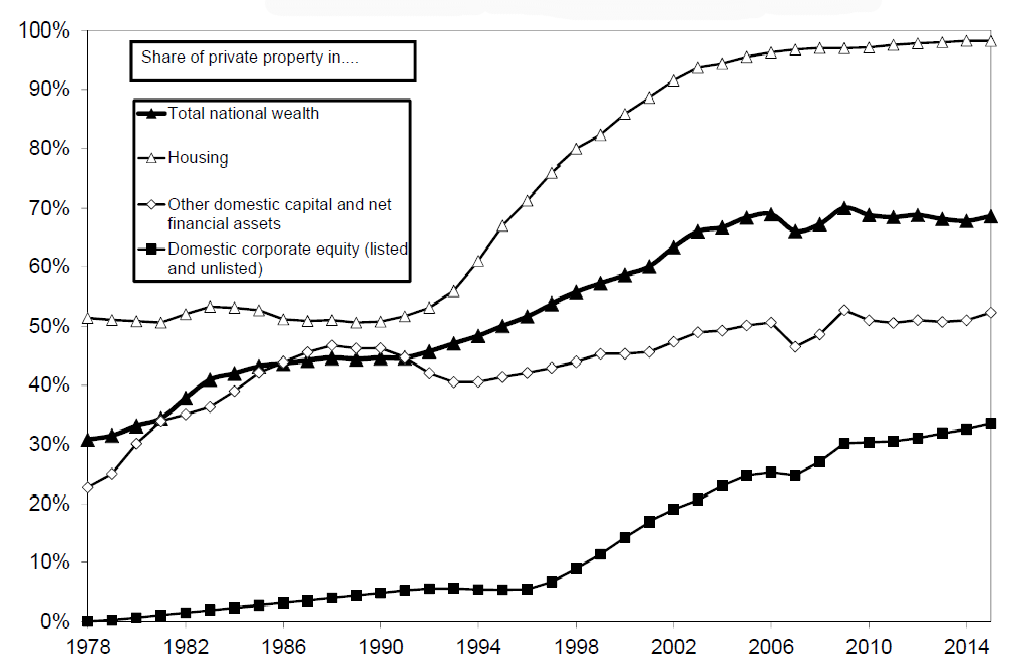

The share of public property in national wealth has declined from about 70 per cent in 1978 to about 30 per cent in 2015. More than 95 per cent of the housing stock is now owned by private households, as compared to about 50 per cent in 1978. Chinese corporations, however, are still predominantly publicly owned: close to 60 per cent of Chinese equities belong to the government (with a small but significant rebound since 2009), 30 per cent to private Chinese owners, and 10 per cent to foreigners — less than in the United States, and much less than in Europe. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4. The rise of private property in China 1978-2015

In brief: China has moved a long way towards private property between 1978 and 2015, but its property regime is still markedly different than in other parts of the world. China has ceased to be communist, but is not entirely capitalist; it should rather be viewed as a mixed economy with a strong public ownership component. In effect, the share of public property in China today (30 per cent) is higher than in the West during the mixed economy regime of the post-World War 2 decades (around 15-25 per cent), but not hugely so. And while the share of public property in national wealth has declined to 0 per cent or even less than 0 per cent in Western countries (with public debt exceeding public assets in the United States, Britain, Japan, and Italy today), the public’s share of national wealth in China seems to have strengthened since the 2008 financial crisis. These findings are not completely unexpected, but we feel that it is important to be able to put numbers on these evolutions.

Income inequality (1978-2015)

By combining recently released tax statistics on high-income individuals with household surveys and national account data, we can provide new estimates of income inequality. To our knowledge, this represents the first attempt to use tax data on high earners to correct inequality statistics in China. (Previous work on income inequality in China was almost entirely based upon household surveys. See, e.g., Piketty and Qian, 2009; Benjamin et al., 2005, 2008; Chi et al., 2011; Chi, 2012; Gustafsson et al., 2008a, 2008b; Khan and Riskin, 2008, 2005; Knight et al., 2016; Knight, 2014; Li, Sato and Sicular, 2013; and Xie et al., 2015, 2013.)

An income tax has been in place in China since 1980, but until recently no detailed income tax data was available, and scholars therefore had to rely on household surveys based upon self-reported information. In 2006, the Chinese tax administration began to release data on the numbers of high-income individuals (i.e., with individual taxable income above RMB 120 000 per annum, equivalent to EUR 11 988), and their incomes.

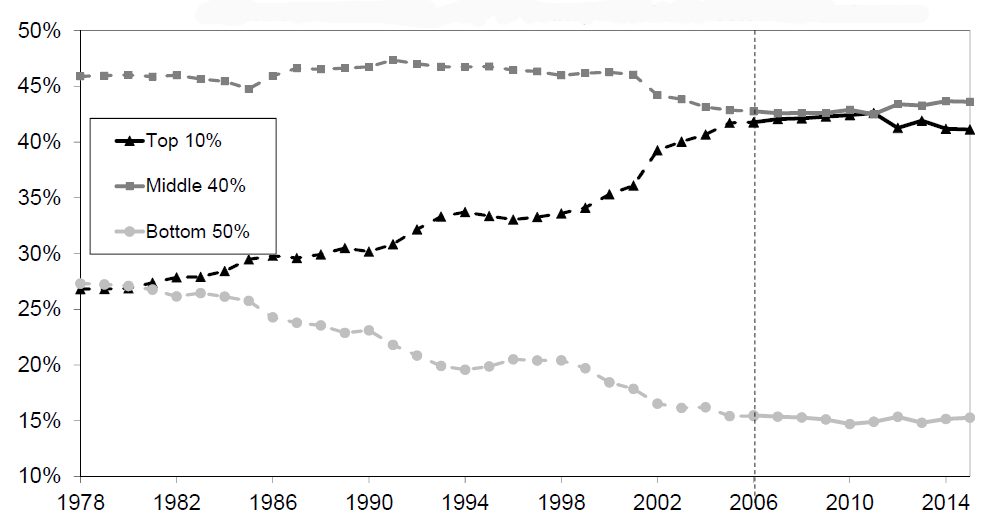

We should make it clear that this data is highly imperfect; our revised estimates might well under-estimate inequality and our top income shares should be viewed as lower bounds. What is interesting, however, is that even these lower bounds are already a lot larger than official survey-based estimates. By our estimates, the share of national income earned by the top 10 per cent of the population has increased from 27 per cent in 1978 to 41 per cent in 2015, while the share earned by the bottom 50 per cent has dropped from 27 per cent to 15 per cent. The bottom 50 per cent of the population used to have about the same income share as the top 10 per cent, while their income share is now about 2.7 times lower. Over the same period, the share of income going to the middle 40 per cent has been roughly stable. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Income inequality in China, 1978-2015: corrected estimates

Note: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unempl. insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates combine survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data. Raw estimates rely only on self-reported survey data. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006-2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

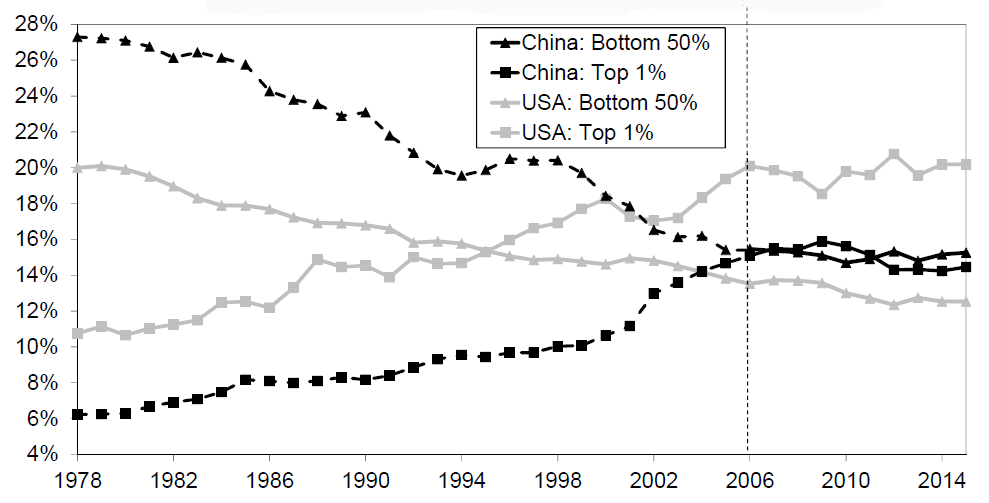

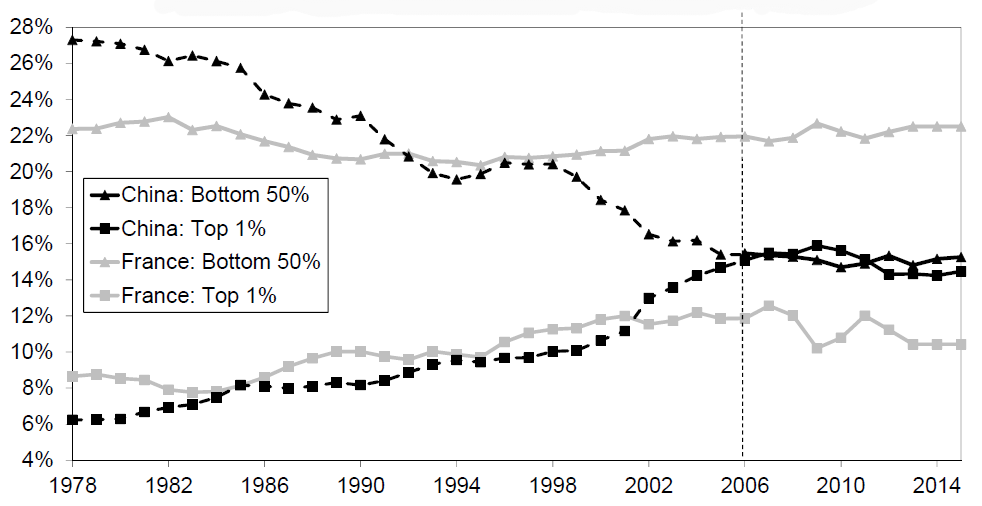

To summarise, the level of inequality in China in the late 1970s used to be less than the European average – closer to those observed in the most egalitarian Nordic countries – but they are now approaching a level that is almost comparable with the USA. In 2015 the bottom 50 per cent in China earn approximately 15 per cent of total national income versus 12 per cent in the USA and 22 per cent in France; while the top 1 per cent earns about 14 per cent of national income, versus 20 per cent in the USA and 10 per cent in France. (See Figures 6a and 6b.)

Figure 6a. Bottom 50% vs top 1% income share: China vs US

Note: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates (combining survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data). Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two).Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006- 2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

Figure 6b. Bottom 50% vs top 1% income share: China vs France

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Corrected estimates (combining survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data). Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Pre-2006 series assume that the tax/survey upgrade factor is the same as the one observed on average over the 2006- 2010 period when national-level tax data exist.

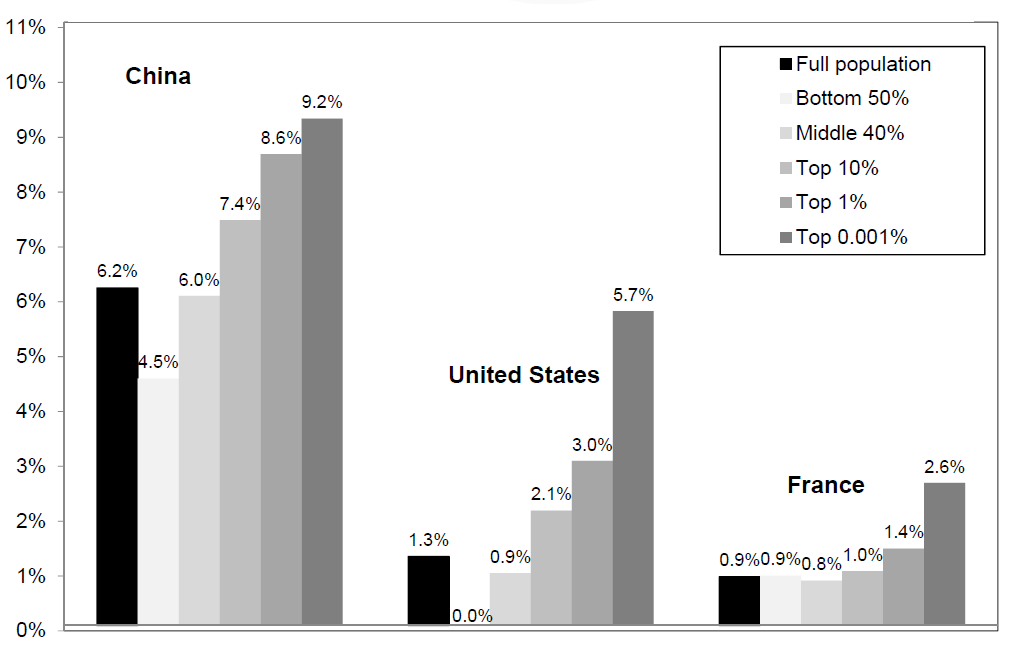

Comparing the average annual growth rate of real per adult pre-tax national income for different income groups in China, U.S. and France from 1978-2015, as shown in Figure 7, the top 1 per cent of the income distribution experienced a growth rate of 8.6 per cent in China, 3.0 per cent in the USA, and 1.4 per cent in France. However, the average annual growth rates for the bottom 50 per cent in China and the US are significantly lower at 4.5 per cent and 0 per cent respectively, while the same figure was 0.9 per cent in France. For the time being, China’s development model appears to be more egalitarian than that of the United States, but less than that of European countries.

Figure 7. Average annual growth rate of real per adult pre-tax national income 1978-2015

Although our new series on income and wealth in China are more homogeneous and comparable than previous attempts, we stress that they still have the potential to be improved as new data sources become available and better methods are designed. (Hong Kong and Macao are excluded from our data — both from the national accounts and from the household surveys, income tax returns, and wealth rankings. This could lead us to underestimate the rise of inequality, and this should be taken into account in future research.)

All the series presented in this paper are available online on the World Wealth and Income Database (WID.world); updated series will be posted there. Our paper is part of a broader international project aimed at producing Distributional National Accounts, which combine national accounts, survey, and tax data in a systematic manner to produce inequality estimates that are homogeneous and comparable across countries. (Piketty, Saez and Zucman (2016) construct distributional national accounts for the United States, and Garbinti, Goupille and Piketty (2016, 2017) for France. These and the present Chinese series all follow the same guidelines (see Alvaredo et al., 2016). New and updated series will be regularly made available on-line on the World Wealth and Income Database (WID.world).)

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper Capital Accumulation, Private Property and Rising Inequality in China, 1978–2015, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

- The post gives the views of the author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Chris Goldberg, under a CC-BY-NC-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

This article is incomplete. Where are the figures for post-tax?