The stakes are high for gender equality in Argentina, which has a chequered history in gender reform. Now the next president might be an extreme-right candidate with an anti-feminist world view. Argentina’s persistent economic challenges have led to frequent changes in government, hindering the political and social will for equality. Simeon Djankov and Karolin Lehmann write that the next election will decide whether a period of stagnation or reform is on the horizon.

On 19 November Argentinians head to the polls again, to select the next president in a runoff between Javier Milei and Sergio Massa, the candidate for the incumbent Peronist government. Javier Milei represents the Libertarian party and runs on a platform to replace the peso with the dollar and abolish Argentina’s Central Bank. In campaign rallies he also says that sex education is a ploy to destroy the family. Milei, if elected, plans on rescinding the 2020 referendum legalising abortion. Known for his anti-feminist views, Milei represents the opposition to the progress made on gender legal reform by previous governments.

As the first Latin American country to implement a parliamentary quota system for women back in 1991, Argentina is experiencing significant push-back from conservative female voters and the younger generation of Argentinean men. The presidential candidate Milei rides on these sentiments by vouching to close the Ministry of Women, which he believes fosters affirmative action that is degrading to women. Sergio Massa is running for the incumbent party, known for the slow response to the increasing cases of domestic violence, femicide and gender pay gaps. The party maintains strong ties to the Catholic Church, which has lobbied to overturn the 2020 referendum legalising abortion.

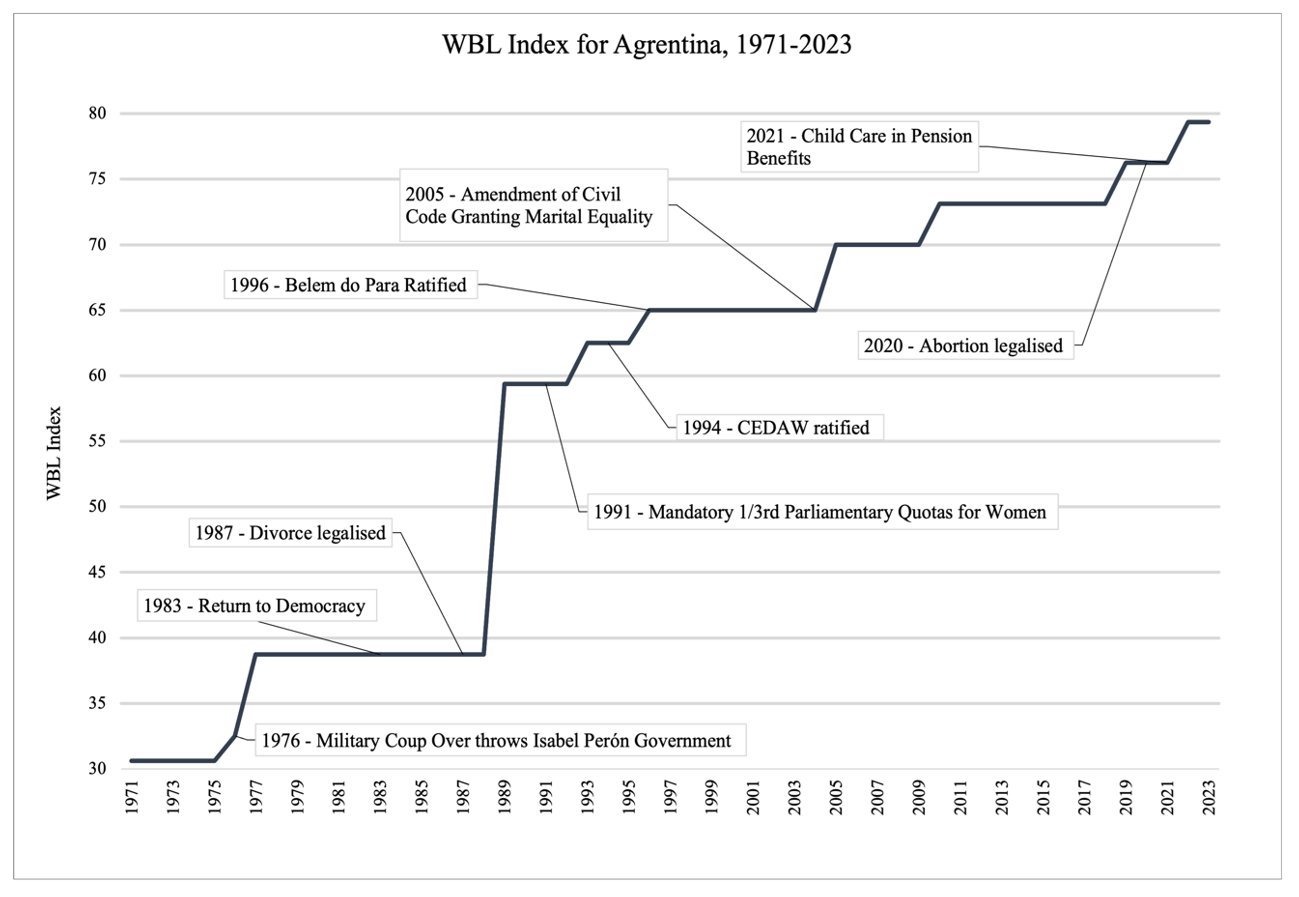

Argentina has long grappled with achieving gender legal equality in the web and flow of its tumultuous political history. Despite a long-standing tradition of female political representation, including two female presidents to date, the road to gender reform has been rocky. As shown in Figure 1, the World Bank’s Women Business and the Law (WBL) index, a global measure of gender equality in the legal system, shows significant strides in Argentina’s gender reform efforts. Yet, in a regional comparison Argentina’s WBL score is among the lowest across every other major economy in Latin America, except for Venezuela. While the country has shown notable improvements in the WBL index over the years, these advancements have struggled to translate to overall female empowerment and are now facing increasingly conservative politics that aim to reverse some of the progress made.

Figure 1. Progress towards gender equality in Argentina

There have been previous reversals in policies related to women’s legal empowerment. The debate over divorce had divided Argentinian public opinion for much of the 20th century, with over a dozen different proposals for the enactment of a divorce provision being introduced to the legislature. In 1954 during Juan Perón’s presidency, a bill introduced providing for divorce to be legal was enacted into law. So divisive was this issue, that ultimately it was one of the main factors that precipitated Perón’s overthrow by the military. The move alienated many military officers who considered it an offence to their religious beliefs. Once Perón was overthrown, the divorce law was repealed too.

Upon the return to democracy, a coalition of lawyers, feminists and legislators lost no time in campaigning for divorce legislation to be re-enacted. They found support within the Women’s National Directorate established in the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs by President Alfonsin in 1983. The law was successfully passed following a Supreme Court ruling saying that the century-old law banning divorce in Argentina as unconstitutional. The ruling drew staunch opposition and criticism from the Catholic Church. However, public opinion was strongly in favour of divorce legalisation, largely due to the large number of couples who had legally separated but were unable to obtain a legal annulment of their marriage. When several Argentine bishops decided to withhold the holy sacrament from legislators who had voted in favour of divorce legislation, widespread public outcry occurred. The Church had overstepped.

Similar policy reversals were seen during Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s first administration in 2008. In order to implement reforms within the agrarian and tax sectors, Fernández needed support from the Church which she brokered in return for a decrease in governmental spending on contraceptives and the cancellation of the successful Salud Sexual program.

Even though Argentina is at the forefront of female political representation in Parliament with 42.4 per cent of seats held by women in 2021, their decision-making power is limited by the highly concentrated system of government. With only a quarter of cabinet ministers and a tenth of governors being women, higher posts within the legislative branch remain male-dominated. Thus, the enduring presence of gender barriers within governmental institutions and decision-making processes underscores the need for sustained activism and advocacy to drive meaningful change.

Argentina’s journey towards democracy has been a testament to the resilience and perseverance of its women’s movements, which have continued to champion gender reform. Women’s rights organisations and grassroots movements have been instrumental in fighting against gender-based discrimination and advocating for legislative changes that promote gender equality and human rights. Movements such as the Green Wave, lobbying for abortion rights in the path to the 2020 referendum, or groups such as the Madres de Plaza de Mayo advocating for human rights showcases the persistent advocacy and activism that have not only amplified the voices of women but have also inspired a broader societal shift towards recognising the importance of gender equality in achieving social progress.

Despite a successful democratic process over the last four decades, Argentina’s persistent economic challenges have led to frequent changes in government, hindering the political and social will for gender legal reform. Argentina’s journey towards gender legal reform is influenced by its political past and the efforts of its women’s group. Extended periods of authoritarian governance resulted in stagnant legal development, interspersed with brief periods of reform. The next election will decide whether period of stagnation or reform is on the horizon.

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.