US taxes and transfers appear to reduce its inequality gap with Europe. Why is it still more unequal, then? Thomas Blanchet, Lucas Chancel, and Amory Gethin write that countries cannot redistribute their way out of inequality. They say that pre-distribution factors, including equal access to education and healthcare, unionisation, and labour market regulation play a dominant role in moderating the rise of income inequality in the twenty-first century.

A common narrative is that the United States’ weaker welfare state is the main reason behind its relatively high levels of inequality compared to other high-income economies, in particular Europe. International organisations and policy analysts commonly push this narrative to focus on progressive taxation and narrowly targeted benefits as the key levers that would allow a fairer distribution of economic growth in the “land of opportunity.”

Our recent research challenges this view. While income gaps in the US are substantially wider than in any European country, perhaps even more so than previously thought, these differences are entirely due to greater pretax inequality, not taxes and transfers. Predistribution, not redistribution, explains why Europe is more equal than the United States.

We construct a new historical database that provides comparable, high-quality statistics on inequality in twenty-six European countries and in the United States since 1980, and we confirm a well-known fact: inequality is significantly higher in the US than in Europe. In 2017, the top 10% of pretax income earners received 48% of income in the US, compared to about 37% in Europe. This was not always the case: at the beginning of the 1980s, the US and Europe displayed comparable levels of inequality. While income disparities rose in Europe in the past forty years, this increase was much smaller than the one observed in the US, resulting in large differences in inequality between the two regions today.

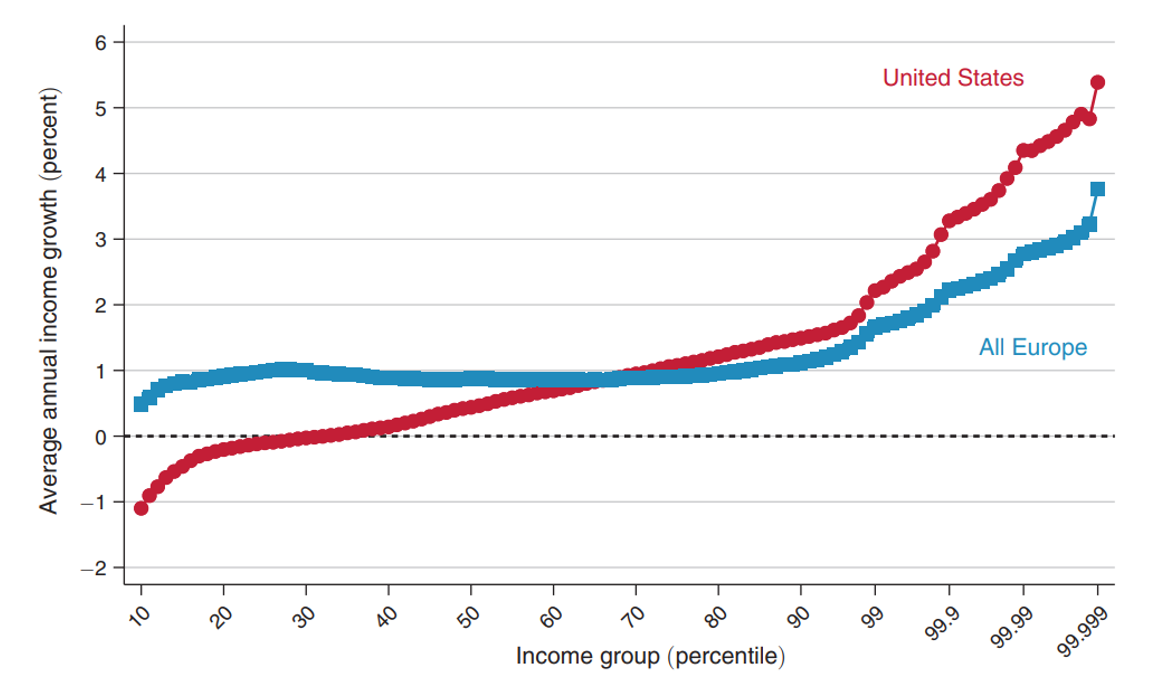

Figure 1 provides a detailed picture of the distribution of economic growth in Europe and the US from 1980 to 2017. The x-axis represents different income percentiles, while the y-axis corresponds to the annual pretax income growth rate that they experienced. Average income growth has been slightly higher in the United States (1.4 percent per year) than in Europe (1.1 percent) in the past four decades, yet this average gap hides substantial differences between richer and poorer segments of the population. The average pretax income of the top 1% grew much faster in the United States than in Europe. Meanwhile, low-income groups have benefited significantly more from macroeconomic growth in Europe than in the US: the average income of the bottom 50% increased in Europe, while it stagnated in the US and even declined for the poorest 30%.

Figure 1.The rise of inequality in Europe and the United States, 1980-2017

The second key result is that taxes and transfers cannot explain why inequality is lower and has risen much less in Europe than in the US since 1980. On the one hand, government spending is lower in the US, so that low-income groups tend to receive lower transfers. Hence, about 13% of national income is received by the poorest 50% of US income earners in the form of social transfers, health, and other public spending today, compared to 18% of national income in France and as much as 23% in Denmark. On the other hand, taxes tend to be more progressive in the US. Indirect taxes, which are regressive because they are paid by consumers, are much lower in the US than in Europe. Social contributions, which in general are either flat or regressive, are more important in Europe. And, finally, the progressive federal income tax in the US collects more revenue than in a number of European countries.

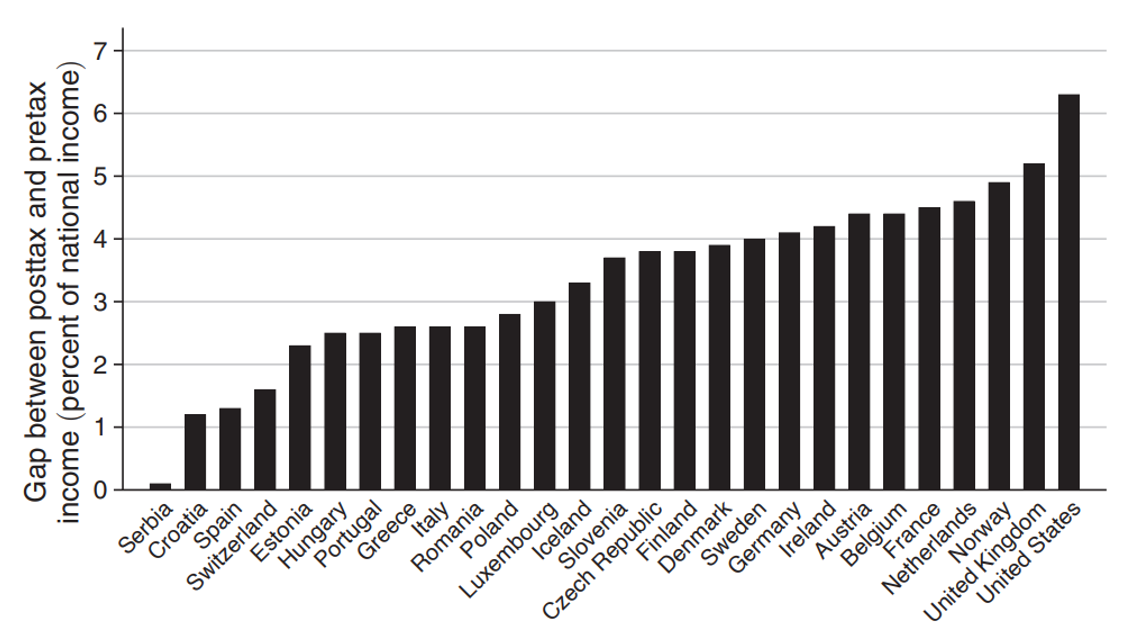

All in all, the US tax-and-transfer system reduces inequality significantly more than that of any European country. As shown in figure 2, the net transfer received by the poorest 50% (that is, transfers received minus taxes paid) was equivalent to approximately 6% of national income in the US in 2017. The corresponding figure stood at 4% in Denmark and just above 1% in Spain. In contrast to a widespread view, government redistribution cannot explain why the US is more unequal than Europe. Quite the contrary: taxes and transfers appear to reduce the inequality gap between the two regions.

Figure 2. Government redistribution is greater in the United States than in Europe

The implications of these findings are quite clear. While progressive taxation and social spending play a key role in alleviating poverty and reducing inequality, they cannot explain well cross-country differences in income inequality today or its evolution in the past decades. Countries do not simply redistribute their way out of inequality. “Predistribution” factors, including equal access to education and healthcare, unionisation, and labour market regulation, play a dominant role in moderating the rise of income inequality in the twenty-first century. This calls for renewed attention to policies enabling a more inclusive distribution of wages and capital income, beyond taxes and transfers, which act as necessary corrective factors but often fail to shape income inequality in the long run.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on Why Is Europe More Equal than the United States?, in American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 14, no. 4, October 2022

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Zack Kiesewetter on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.