Policymakers the world over are exploring a range of strategies to mitigate and adapt to greenhouse-gas emissions and manage the unavoidable effects of climate change.

At the 21st Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21), representatives agreed to keep any increase in global average temperature within 2°C of pre-industrial levels and also to set country-specific nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Mexico, for example, pledged a 30 per cent reduction in emissions by 2020, rising to 50 per cent by 2050. To this end, Mexico has implemented climate policies such as the General Law on Climate Change (2012), which promotes the development of economic instruments such as carbon taxes and emissions-trading systems to incentivise companies to reduce their greenhouse-gas emissions. As national and international standards in this area become more robust, companies are increasingly forced to recognise the costs of their exposure to climate risk.

Climate risks and company performance

The implementation of climate policies targeting greenhouse-gas emissions will increase costs for companies in the many sectors that rely on fossil fuels. If producers then transfer these costs to consumers, the prices faced by end-users will also increase. In the long term, consumers will be obliged to use alternative renewable-energy technologies, which will lead to shifts in demand and reduce firms’ revenue.

Investors, meanwhile, are concerned about the degree of exposure to climate risk in their portfolios, particularly because the frequency, severity, and long-term impact of climate change are not only uncertain, but also immune to diversification.

Experts divide climate risks into three major categories:

- Physical risk refers to the direct impacts stemming from changes in climate patterns and extreme climate events.

- Transition risk relates to the commercial resilience of current business activities to regulatory changes.

- Litigation risk involves liability to compensate for damages caused by business activities with negative impacts in areas such as climate, health, ecosystems, or air and water quality.

What are international investors doing to minimise their exposure to climate risk?

Institutional investors evaluate the financial impacts of climate risks before deciding to invest in a pool of assets. Once an investment vehicle has been selected, the performance of the asset value is monitored over the investment period to detect and avoid losses. For this reason, investors are encouraging companies to disclose details of exposure to climate risks so as to enable better decisions on allocation.

The Financial Stability Board, which monitors and advises on the global financial system, acted on input from financial sector representatives by creating the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in December 2015. The Task Force is made up of banks, pension funds, insurance companies, asset managers, and credit-rating agencies, which together were able to agree on a standardised framework for climate risk disclosure in June 2017.

Climate-risk exposure and development banks: the case of Mexico’s NAFIN

Development banks come at climate risk from a slightly different angle than commercial banks, not least because investment decisions involve both public-interest and strictly financial considerations.

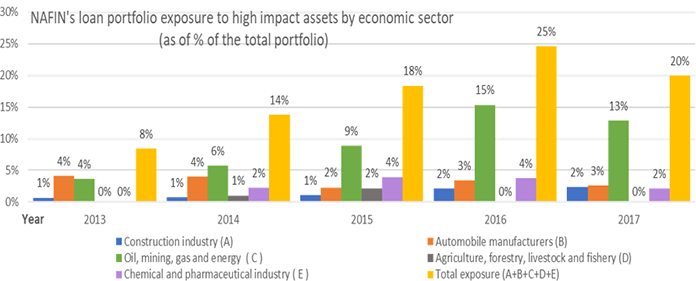

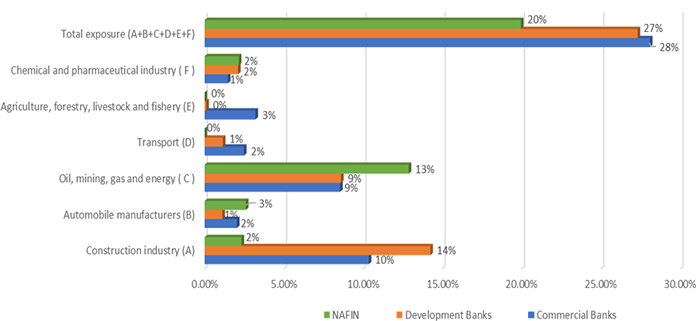

In the case of Mexico’s NAFIN, financial reforms in 2014 led to investment in sectors with high climate-change impact because of the bank’s mandate to finance sectors underserved by commercial banks: energy, oil, gas, and infrastructure feature prominently here (see below). In this sense, exposure does not necessarily indicate a tendency to contract riskier loans, rather that these kinds of investment relate to NAFIN’s developmental role.

Figure 1. Performance of NAFIN loan portfolio exposure

Figure 2. Exposure by sector, NAFIN and wider banking system

The Mexican energy sector in particular has undergone many changes since the Energy Reform initiative was launched in 2013. The most significant is the new requirement of compliance with Mexico’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) within the COP21 framework as part of a transition towards a low-carbon economy.

The changes come in a context of rising incomes and population growth, which are together expected to fuel a 20 per cent jump in demand for energy by 2040. The challenge is to cover that demand without increasing CO2 emissions, and clean energy technologies represent the only path towards this crucial goal.

Furthermore, as with Latin America’s many extractive economies, Mexico’s reliance on oil-export revenues leaves the country sensitive to changes in oil production and prices. The implementation of climate change policies in importing countries means there is a significant risk for the Mexican oil sector from weaker demand and lower prices in future, with a knock-on effect for companies dependent on export activities.

Climate policies that encourage companies at home and abroad to reduce their emissions and promote the sustainable use of energy will increase the direct and indirect costs borne by Mexican firms. As such, climate-transition risks for investments in carbon-intensive sectors will increase significantly.

Expected losses to the world’s current stock of assets as a result of climate change are valued at $4.2 trillion by 2100, but these losses will be halved if mitigating actions are taken. Investments in low-carbon sectors thus become more attractive, as they can minimise the risk of “stranded assets” (those suffering shock devaluations) and provide opportunities for diversification and long-term, risk-adjusted returns within portfolios.

Improving governance mechanisms to attract international investors

Development banks whose loan portfolios are exposed to climate-transition risks can mitigate those risks by implementing governance mechanisms that improve management and transparency of climate risk within loan portfolios, as stipulated by the TCFD framework.

The first step for development banks such as NAFIN is to integrate national and international climate strategies into key objectives. Inclusion of targets for decarbonisation of loan portfolios within overarching objectives will help the bank translate commitments into operational lending criteria. NAFIN should then ensure that loans are allocated with low-carbon transition and resilience in mind. Internal shadow carbon pricing can be helpful here since it allows high-emission projects to slide down the scale of priorities. NAFIN should also develop processes that identify risk factors in transition scenarios and assess their financial impacts over time, using climate-scenario analysis as the primary tool.

Integration of climate action into NAFIN’s strategy and structure, as well as readiness to collaborate with external bodies, would also be positive steps. Internally, the board of directors must build a climate-change framework throughout all levels of management and operations. The climate-change unit and the committee should observe the implementation of climate strategies, while the risk-management unit and its committee must oversee the alignment of the operative processes to the framework and climate exposure levels authorised. Credit experts need to identify the financial impacts of climate change on the creditworthiness of borrowers, and human resources personnel will be vital in creating new institutional roles focused on achievement of climate-change commitments. Externally, banking associations, regulators, and supervisors will play a part in protecting the banking system from climate-change issues.

The commitments and institutional targets defined by the bank have the primary purpose of improving the climate performance of NAFIN. However, rigorous policies for monitoring and reporting would increase the effectiveness of these measures. As such, NAFIN should assess greenhouse-gas emissions at the project-appraisal stage for all of its products.

Finally, NAFIN should implement a transparency policy stipulating annual disclosure of organisational oversight on climate change, strategies in place to identify climate risks, climate-risk assessment processes, and any metrics and targets applied. As noted by the TCFD, from an investor’s point of view, this is how decision-useful disclosure would need to be implemented.

Climate change is increasingly recognised as the major global challenge of our shared present and future, and the political will to rise to this challenge is growing by the day. Though new climate risks imply significant reforms for development banks like NAFIN, timely assessment and adaptation will allow the bank to continue to transfer competitive rates to the micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises and strategic investment projects that are so crucial to Mexico’s economic prospects.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared originally on LSE’s Latin America and Caribbean. It is based on the author’s paper Assessing and Managing Climate Risk Exposure, NAFIN Fellowship Programme Working Paper No 3 (2019), in partnership with LSE’s Latin America and Caribbean Centre (LACC) and Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Hans, under a Pixabay licence.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Marisol Rentería Bravo held the third NAFIN Visiting Fellowship hosted jointly by the Latin America and Caribbean Centre and the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment at the LSE.

Marisol Rentería Bravo held the third NAFIN Visiting Fellowship hosted jointly by the Latin America and Caribbean Centre and the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment at the LSE.