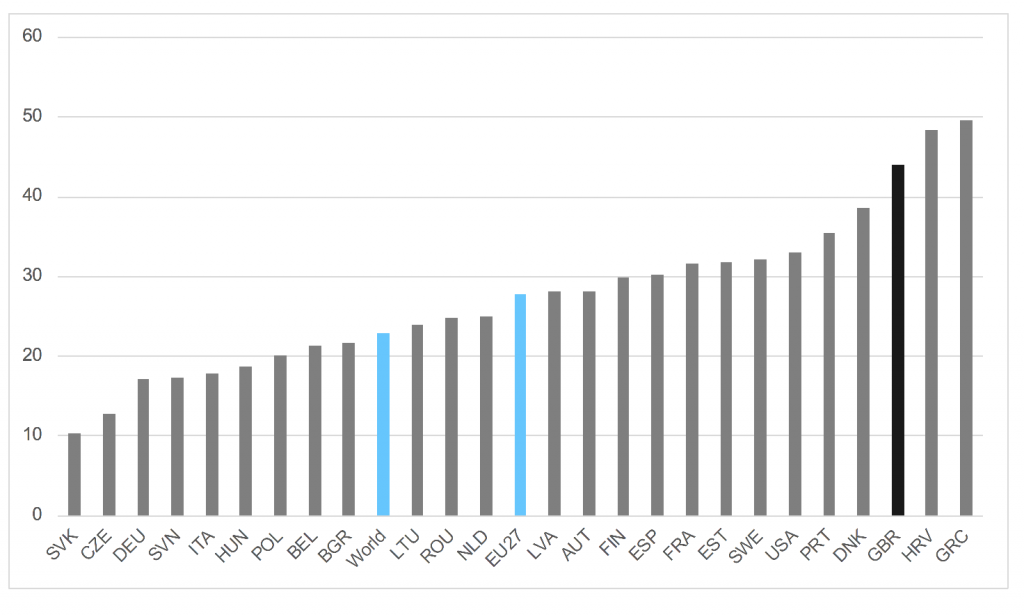

In the Brexit debate, trade in services has been largely overlooked in favour of trade in goods. This is despite the UK being the second biggest exporter of services in the world and having one of the highest shares in total exports among leading economies (Figure 1). Moreover, the EU is a major market for UK services, having accounted for about 49 per cent of the country’s total services exports in 2017.

Figure 1. Share of cross-border services exports in total exports in 2017*, %

Notes: * Excluding outliers Luxembourg, Cyprus and Ireland. Source: WTO

When talking about sector specialisation of services exporters, London, as the UK’s financial hub, comes to mind. But the UK is competitive in a broad range of services, with ‘other business services’ – a combination of legal, accounting, management consulting, and public relations services – being most prominent in cross-border trade, having accounted for 33.5 per cent of the sector’s total exports in 2016 according to WTO data. The second biggest subsector is architectural, engineering, scientific, and other technical services (14.6 per cent), followed by advertising, market research, and public opinion polling services (10.1 per cent). In the transport sector, air transport accounts for almost two-thirds of exports.

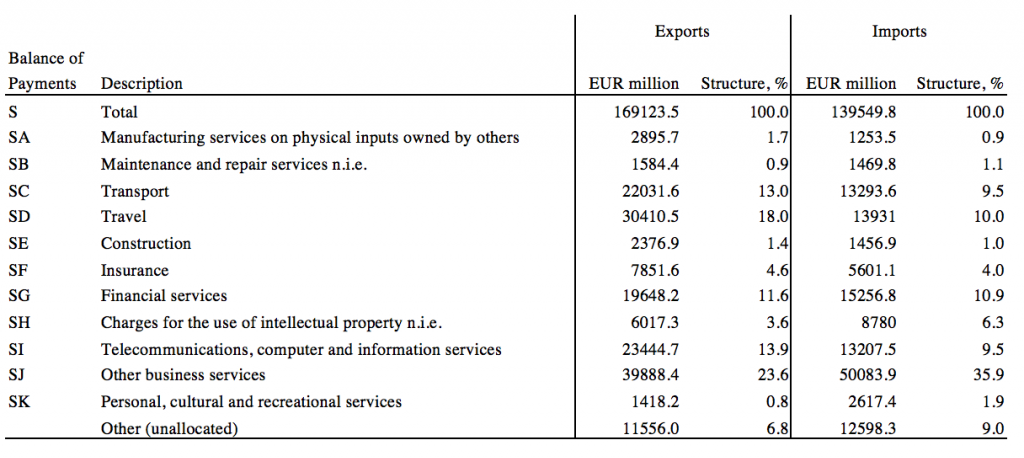

Table 1. Sector structure of UK cross-border services trade (modes 1+2) with the EU in 2016

Source: Eurostat. Mode 1 – Cross-border: services supplied from the territory of one country into the territory of another country. Mode 2 – Consumption abroad: services supplied in the territory of one nation to the consumers of another nation.

As a member of the single market, the UK has access to a market of over 500 million consumers, to the free flow of data between EU members, and to passporting rights, which allow financial companies to sell services in any EU country without having to set up a branch there. In other words, the single market allows the UK to supply more services through cross-border trade rather than through costly commercial presence. Passporting rights are also a very important reason why the UK has been used as an EU base by US and Japanese financial firms.

Important for the professional services sector is also the free movement of people. For example, UK companies can employ European staff in the UK or send their workers on trips to the EU to consult clients, provide technical support to users of their products, broker and draft contracts, and so on. As migration concerns were crucial for the Brexit vote, movement restrictions are probably the most binding constraint on the government, making free movement unlikely to be a part of any deal, which significantly limits the options available for the services trade.

If the UK opts for a divorce that precludes it from participation in the single market in services, it will inevitably face increased regulatory costs: relevant providers in the UK will face heterogenous regulations in each member state, which implies an increase in trading costs. With a rise in cross-border trade barriers there would also be a relative increase in the proportion of services provided via a more costly commercial presence within the EU. The process has already started due to the political uncertainty that has surrounded Brexit since 2016, and has so far been most visible in the financial sector, where more than 250 firms have moved or are moving business elsewhere.

The biggest losses would take place if the country crashed out of the EU without any agreement and had to trade with the bloc on WTO terms, which envisage a very limited scope of liberalisation under the General Agreement on Trade in Services. Even concluding a free trade agreement with the EU will result in a significant rise in the barriers to services trade – the EU’s recent agreement with South Korea and Japan, for example, does not address regulatory issues around authorisations and licensing, with processes varying between member states.

It is nonetheless possible that Brexit could result in more advanced services liberalisation than previous EU agreements. But in order to achieve this, any preferential access to the EU market that the UK might seek will need to be part of a comprehensive agreement, otherwise the EU may be obliged to extend more favourable conditions to its other trading partners according to the most favoured nation principle. Politically feasible options of such an agreement are deals similar to the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement or CETA+, which offer limited scope of liberalisation. The UK could possibly secure mutual recognition that would cover some professional qualifications and licensing for various sectors. Still, the scope of a deal will most likely be limited.

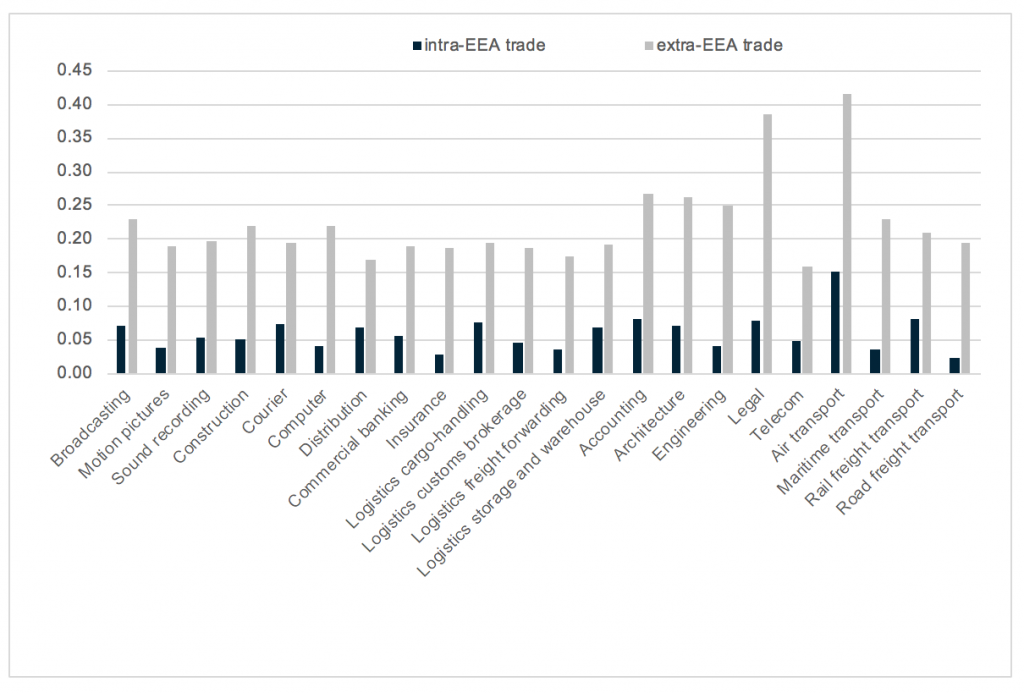

Comparison of the values of the OECD Services Trade Restriction Index for intra- and extra-EEA trade (Figure 2) shows that countries outside the single market face the highest barriers to trade with EEA members in air transport and a range of professional services: legal, accounting, architecture, and engineering. It is in these sectors that the UK is likely to experience the highest increase in trade costs.

Figure 2. EEA Services Trade Restriction Index in 2018, simple average across countries

Source: OECD, author’s calculations

The US is the most important market for UK services exporters outside the EU (20.5 per cent of total services exports in 2017), but substantial reorientation of British services exports to this and other non-EU markets is unlikely as geography matters to services trade almost as much as to trade in goods. This is due to factors such as the need of face-to-face interactions, the inconvenience of operating in different time zones and so on, all of which tend to result in services exports being quite localised geographically.

Just how severely Brexit will affect the services trade will depend on the form it takes; however, it seems increasingly likely that under all feasible options the UK will face increased regulatory costs.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on LSE British Politics and Policy. It is based on the author’s report The Future of UK Services Trade Post-Brexit: Unlikely to Be Bright, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW) Policy Notes and Reports 31, June 2019.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Aleem Yousaf, under a CC-BY-SA-2.0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Olga Pindyuk is an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. Her research focuses on foreign trade, trade in services, international economics and financial markets. She is also country expert for Kazakhstan, Ukraine and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). She has extensive experience with services trade data and does research on modelling trade costs in services trade and on linkages between producer services trade and manufacturing. Previously, she worked as a consultant with the World Bank (Ukraine office) and the DFID Ukraine Trade Policy Project.

Olga Pindyuk is an economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. Her research focuses on foreign trade, trade in services, international economics and financial markets. She is also country expert for Kazakhstan, Ukraine and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). She has extensive experience with services trade data and does research on modelling trade costs in services trade and on linkages between producer services trade and manufacturing. Previously, she worked as a consultant with the World Bank (Ukraine office) and the DFID Ukraine Trade Policy Project.