As industry boundaries are reshaped by digitisation, firms are developing more continuous and open-ended relationships with stakeholders as well as more intense coordination among firm functions across the value chain. However, strategically responding to the new digital landscape requires rethinking how digital business models can most securely lock-in customers. I argue that, when coupled with other foundational digital strategies, leveraging the digital switching costs outlined in what I call the “Digital Lock-in/VEIF Model” can relatively securely lock-in customers and therefore offer prolonged market dominance.

Digital network effects vs. digital switching costs

It is understood that network effects (i.e., the increase in value accruing to users of a product/service and potentially others when a new user joins the group consuming that product/service) can create switching costs (i.e., the costs of transitioning from one supplier to another). Together, these phenomena can create lock-in effects (i.e., the lack of desire or inability to move to an alternative supplier), which in turn create competitive advantages, especially for early movers.

Yet not all network effects generate the same value. And digital businesses experience different network effects than those in the physical-world because they are not as directly tied to hardware.

Moreover, in order to create prolonged digital lock-in, strategists must better appreciate that switching costs in the digital world, in contrast to the physical world, are not inevitable bi-products of network effects. For example, it is often easier to compare the price and quality, based on customer ratings, of competitors’ offerings across digital platforms which effectively reduces information asymmetries that once locked-in customers in the physical-world. More generally, it is possible for a digital network to grow while the costs of switching networks remains very low.

In response to this new techno-economic reality, rather than only relying on digital network effects, digital businesses can leverage the Digital Lock-in/VEIF model to create sustained customer lock-in.

The Digital Lock-in/VEIF model

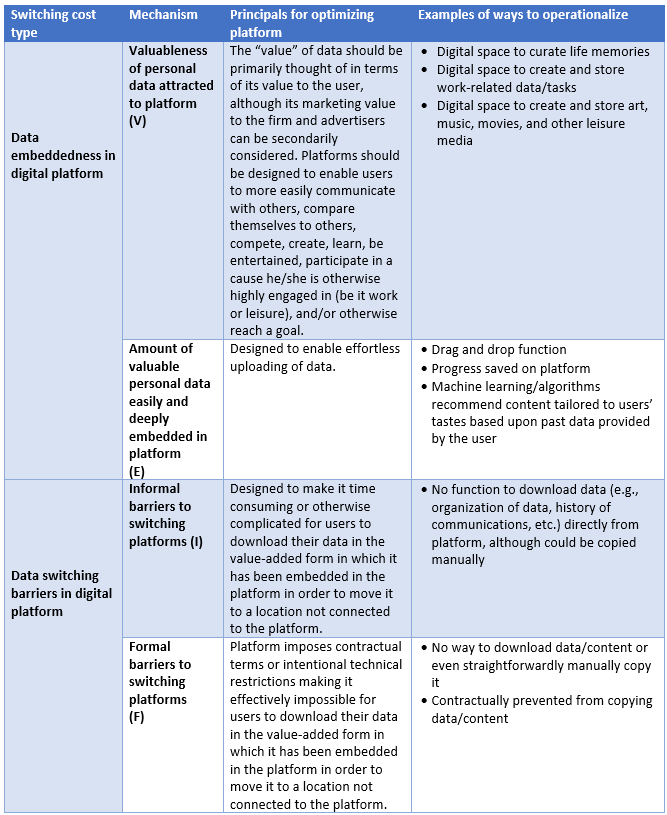

The Digital Lock-in/VEIF model outlines two main types of digital switching costs: (1) valuable data embeddedness and (2) data switching barriers. These two costs – which have roots in strategy, psychology, and technology studies – must be employed together, as one without the other does not securely lock-in customers. Figure 1 presents the model.

Figure 1. Digital lock-in/VEIF model

Firms have excelled in some mechanisms in the VEIF model in sometimes very different ways. For example, Facebook has excelled in the “V” mechanism (valuableness of personal data attracted to platform) by providing a platform to curate and compare life stories. Several firms have excelled in the “E” mechanism (amount of valuable personal data easily and deeply embedded in the platform), for example Microsoft One Drive incorporates an effortless drag-and-drop function, Riot Game’s League of Legends allows saving video game progress online, and Google Play Music uses machine learning/algorithms to recommend content tailored to users’ tastes based upon past data provided by the user. In terms of the “I” mechanism (informal barriers to switching platforms), it is difficult for Facebook and Linkedin users to move all of the media, contacts, and memories they curate on those platforms to another platform. League of Nations players seek to accumulate points and advance to different levels of the game over relatively long periods of time, deterring them from leaving for another video game. In terms of the “F” mechanism (formal barriers to switching platforms), Google Play Music users are unable, contractually and technically, to download the music that they have saved to their app-based library to another platform unless they separately purchase each song or album.

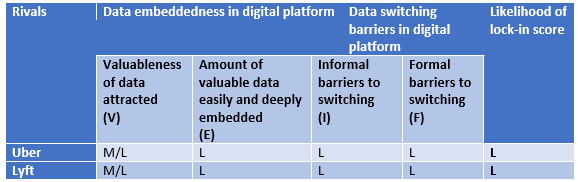

There of course are also firms who have not developed adequate VEIF mechanisms. For example, the user data embedded into Uber’s and Lyft’s digital platforms (both ride hailing apps) is not particularly unique or valuable to users, nor are there particularly significant amounts of such data embedded into the platforms. This allows easy switching between platforms which limits both firms’ long-term ability to securely lock-in customers – a conclusion validating other recent research.

The VEIF Scorecard (see Figure 2) is a straightforward tool for visualising how competitors stack up on the VEIF mechanisms. The greater the “likelihood of lock-in” score, according to the scorecard, the more likely a digital business is to retain customers, assuming other fundamental strategies for designing a successful digital business are also followed. The example provided in Figure 2 illustrates the cases of Uber and Lyft.

Figure 2. VEIF scorecard (example)

Notes: H = High, M = Medium, L = Low. Alternative scales could be used, including but not limited to 1-3 Likert scales. Alternative weightings for the sub-totals from the VE and IF, and the final Likelihood of lock-in score, could be used.

Market dominance through digital lock-in

The Digital Lock-in/VEIF model, on its own, is a helpful tool for thinking about how to leverage digital switching costs to more securely lock-in customers in the digital era. However, it is not for every business. It may be best suited to, although not restricted to, the media and entertainment, information storage and data processing, and educational industries. For firms to make use of the VEIF model, their own business models need to be almost entirely devoted to delivering non-perishable core products/services online. Further, the VEIF model should be combined with a validated revenue-generation model suited to each firm’s digital products/services: freemium leveraging reputational capital, subscription-based, ad-based, and other online fee-based models, or a combination thereof can be used.

By following the model and timely rolling out complementary products/services and pursuing other smart digital strategies, a digital business should be able to relatively securely lock-in customers, helping it achieve prolonged market dominance. The challenge then may be avoiding being too dominant, as digital tech giants such as Facebook are now discovering amidst threats of anti-trust investigations.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The author thanks Jonathan Peillex and Imane El Ouadghiri for suggestions on some case studies to include in this article.

- This blog post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by geralt, under a Pixabay licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Dan Prud’homme is an an associate professor at EMLV Business School (Paris, France) and non-resident research associate at Duke University’s Kunshan, China campus. Prior to joining academia, he worked in the private sector in Beijing and Shanghai, China. Dan holds a PhD from Macquarie Graduate School of Management (Sydney, Australia) and graduate degrees in law and public policy.

Dan Prud’homme is an an associate professor at EMLV Business School (Paris, France) and non-resident research associate at Duke University’s Kunshan, China campus. Prior to joining academia, he worked in the private sector in Beijing and Shanghai, China. Dan holds a PhD from Macquarie Graduate School of Management (Sydney, Australia) and graduate degrees in law and public policy.