The sale of state-owned firms can help political corporations to emerge and persist over time. Felipe González, Mounu Prem, and Francisco Urzúa show that the Pinochet dictatorship sold many firms to politically connected buyers at a price below market value. These newly private firms benefited financially from the dictatorship and, once democracy arrived, they formed connections with the new democratic government, financed political campaigns, and many appeared in the Panama Papers.

Political corporations in Chile can be traced back in time to the sale of state-owned firms during the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990). Using newly collected data, we characterise this historical process and find that many of these firms were sold to allies of the regime, i.e., to politically connected buyers, at a price below their market value. By comparing similar firms that were privatised differently, we can observe that the ones sold to connected buyers benefitted financially from the Pinochet regime. Once democracy arrived, these firms formed connections with the new democratic governments, financed political campaigns, and were likely to appear in the Panama Papers. These findings reveal how dictatorships can influence young democracies and document how privatisation reforms help political corporations to emerge and persist over time.

The analysis builds on several newly constructed datasets. First, we digitise annual firm-level reports with balance sheet information, income statements, and the names of owners and board members. We focus our empirical analysis on firms that submitted annual reports and were sold by the Pinochet regime. Second, we characterise each one of these sales using data on buyers and sale prices. Finally, we use the names of owners, board members, and politicians to detect political connections and identify firms engaged in campaign finance and tax avoidance as revealed by the Panama Papers.

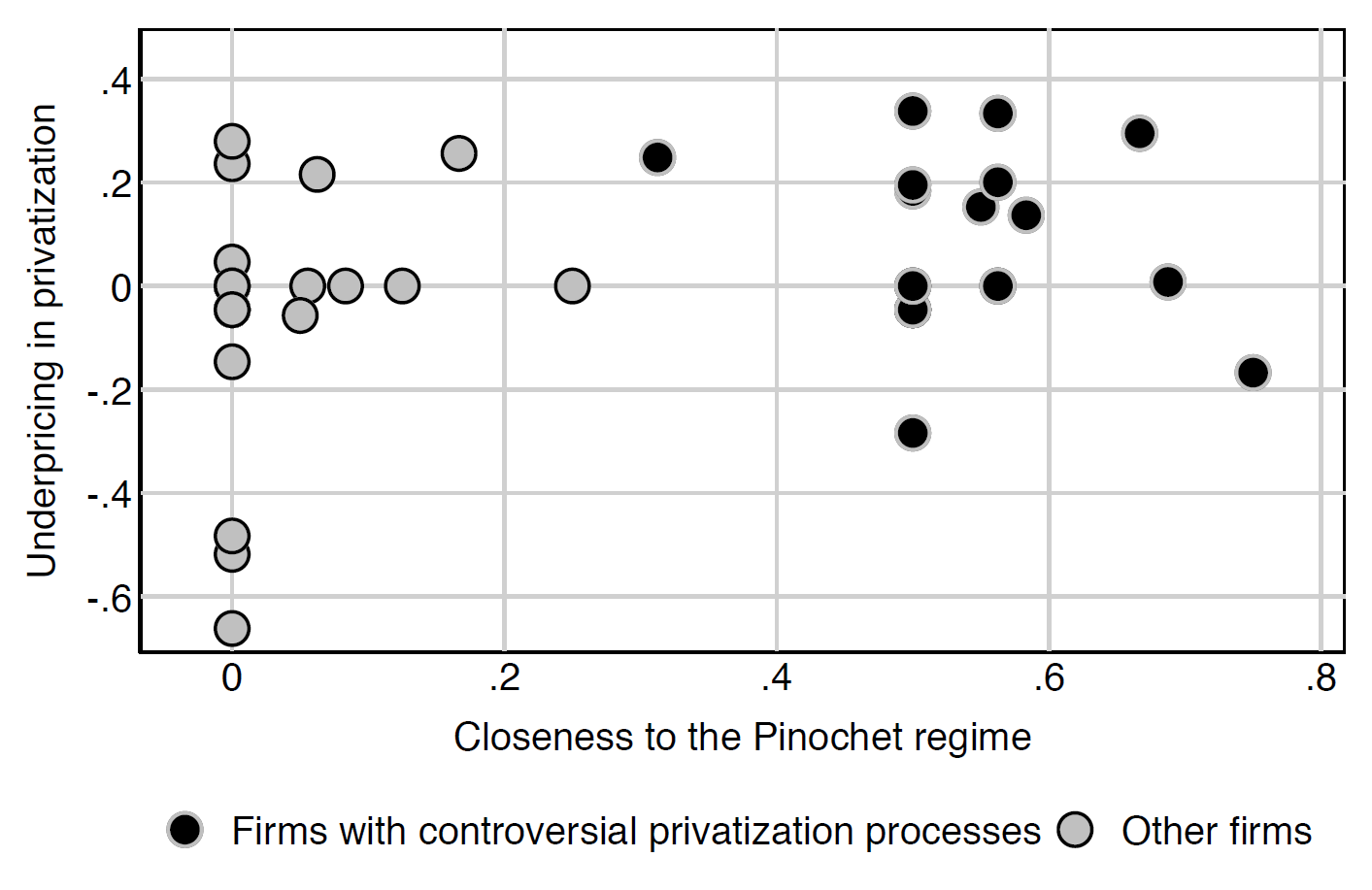

We classify privatised firms into different types of sales using a data-driven algorithm. Book values, balance sheets, and the names of people involved in the transactions allow us to construct relative measures of a) under-pricing and b) social distance between buyers and the Pinochet regime. The former reveals striking differences in sale prices and the latter shows that some buyers were closely connected to Pinochet and others had no relationship at all. This two-dimension classification permits the exploitation of a clustering algorithm to detect two groups of firms. We find that a group of firms was sold under their market price to buyers who were closely related to Pinochet. Many have referred to processes with these characteristics as “controversial privatisations.”

Figure 1. Firms sold below market value and buyers’ closeness to the Pinochet regime

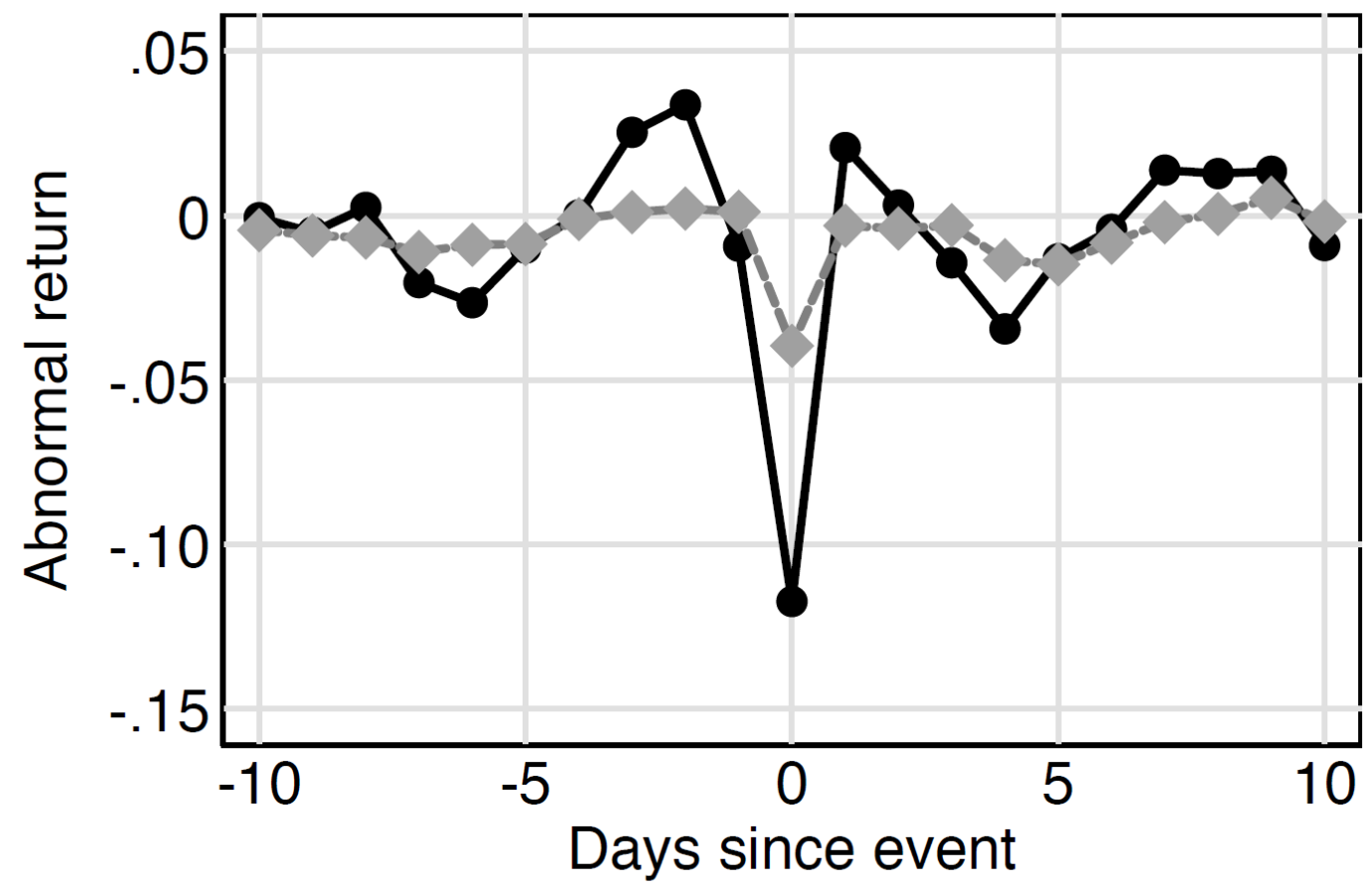

After constructing the data and detecting types of privatisations, we compare firms with controversial processes to other privatised firms before they were sold. Remarkably, the two types of firms had similar indebtedness and performance, suggesting that controversies were unrelated to firm behaviour and industry dynamics. There are, however, differences in firm size for which we control. The day after the 1988 referendum, which ended the Pinochet regime, firms with controversial privatisations experienced an eight percentage points decrease in abnormal stock returns. This result is consistent with controversial firms obtaining benefits from Pinochet (Fisman 2001).

Figure 2.

Motivated by the reaction of financial investors, we study the evolution of economic and political outcomes by comparing controversial and otherwise similar uncontroversial privatisations within industries. To begin with, we focus on the short run after privatisation and study debt financing between privatised firms and state-owned banks, since previous research has shown companies may use these institutions to extract rents (Khwaja and Mian 2005). Then, we study the political behaviour of firms after Pinochet left power in 1990 by analysing the relationship between controversial privatisations, political connections over time, campaign finance, and tax avoidance.

Our analysis reveals that firms with controversial privatisations acquired more loans from state-owned banks toward the end of the regime (1988–1990). In contrast, we do not observe these differential interactions between controversial firms and other types of banks. These results help to explain our stock market results, are consistent with previous findings on preferential access to finance by firms closely linked to the Pinochet regime (González and Prem 2020), and constitute additional evidence suggesting these firms benefited from the regime. Our econometric strategy uses the unexpected outcome of the 1988 referendum and an analysis of loans from the main state bank, private banks, and international banks before and after the referendum.

After the transition to democracy, in March 1990, firms with controversial privatisations formed connections with the new democratic governments, financed the political campaigns of left- and right-wing candidates, and were more likely to appear in the Panama Papers. Controversial firms employed politicians 25 percentage points more often and established connections with the new government in place of the old connections to the dictatorship: by 2005 controversial firms were 40 percentage points more likely to employ a politician from the new government. This finding is important because this type of political connection has been associated with resource misallocation (Cingano and Pinotti 2013) and produces economic rents for connected individuals (Blanes i Vidal, Draca, and Fons-Rosen 2012). Finally, recently declassified documents permit us to show that controversial firms were 31 percentage points more likely to engage in campaign finance and 36 percentage points more likely to appear in the Panama Papers.

Pinochet’s privatisations offer several lessons regarding the business world, politics, and the links between these two. First, poorly monitored privatisation reforms can create firms with significant political influence. Second, authoritarian regimes can affect the functioning of young democracies using policies to take control of firms. And third, our work sheds light on mechanisms used by businesspeople linked to authoritarian regimes to extract rents. Market and institutional structures can shape firm behaviour by affecting the marginal returns and costs of lobbying in new democracies. Dictatorships create economic rents and political connections lower the costs of protecting these.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The Privatization Origins of Political Corporations: Evidence from the Pinochet Regime, The Journal of Economic History.

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen, under a CC-BY-SA-4.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.