The negative impact of climate change on local economic activity has been well studied. However, so far, we have lacked a clear understanding of how it affects the allocation of labour and capital. Christoph Albert, Paula Bustos, and Jacopo Ponticelli use new data on extreme weather events that occurred in Brazil during the last two decades and write that prolonged droughts cause the reallocation of capital and labour away from affected regions, effectively changing the structure of the economy in both directly affected areas and those integrated via labour and capital markets.

The economic and social impact of climate change is the major challenge of our time. Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes across the globe, including heatwaves, heavy precipitation, and droughts, according to the UN body assessing the science related to climate change (IPCC, 2021).

Developing countries, which are often located in (sub)tropical regions with already high temperature levels and have a high agricultural employment share (Mani et al. 2018), are particularly exposed to extreme weather events. Several studies show that increases in temperature and extreme weather have negative effects on local economic activity and generate migration away from affected areas (see Dell et al. 2012 for a review). However, we still lack a clear understanding of how climate change affects labour and capital reallocation, including its impact on destination regions for factors displaced by climate shocks.

In our recent paper (Albert, Bustos and Ponticelli, 2021), we study this question using new data on extreme weather events that occurred in Brazil during the last two decades, focusing on excessive dryness.

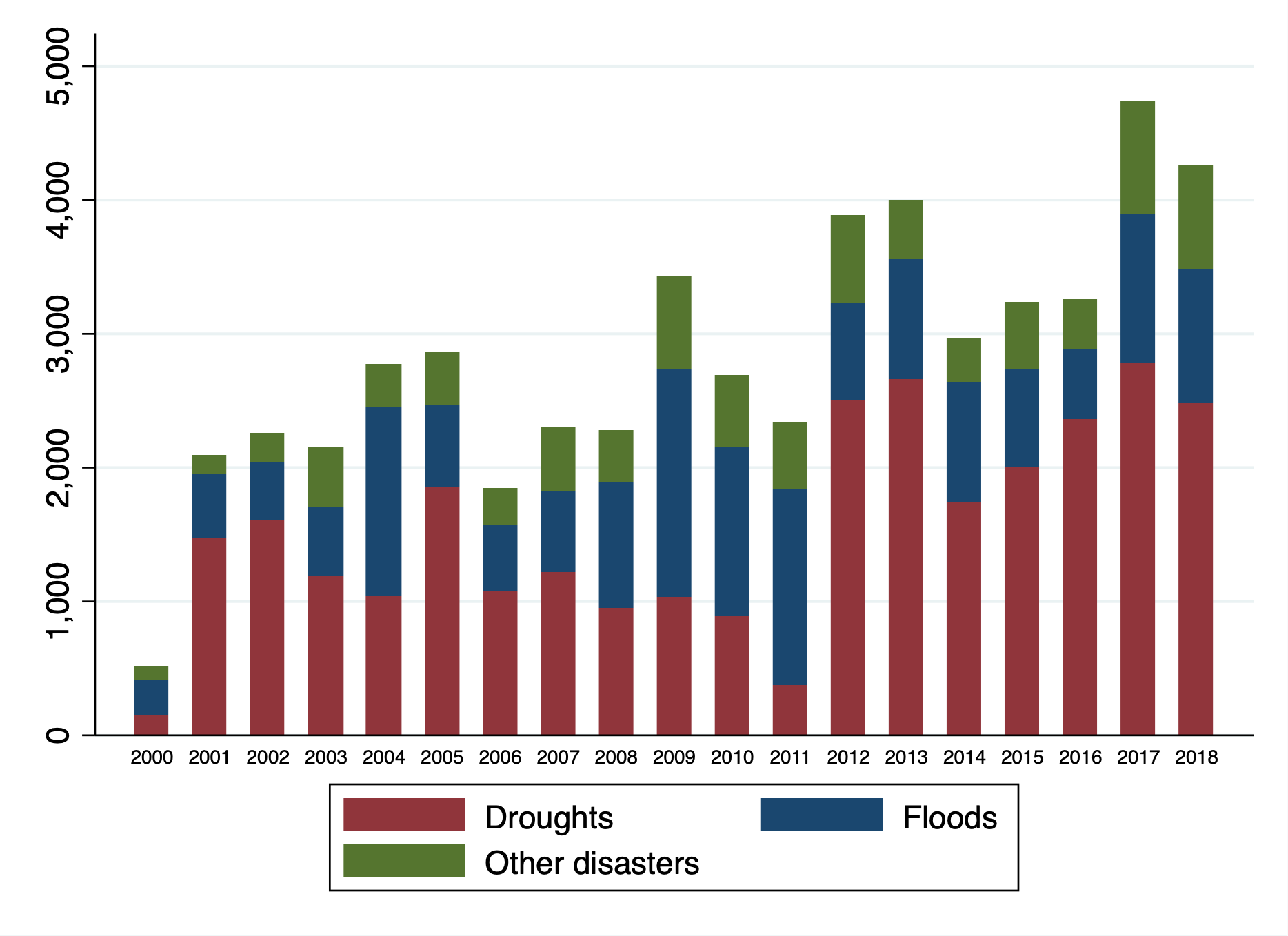

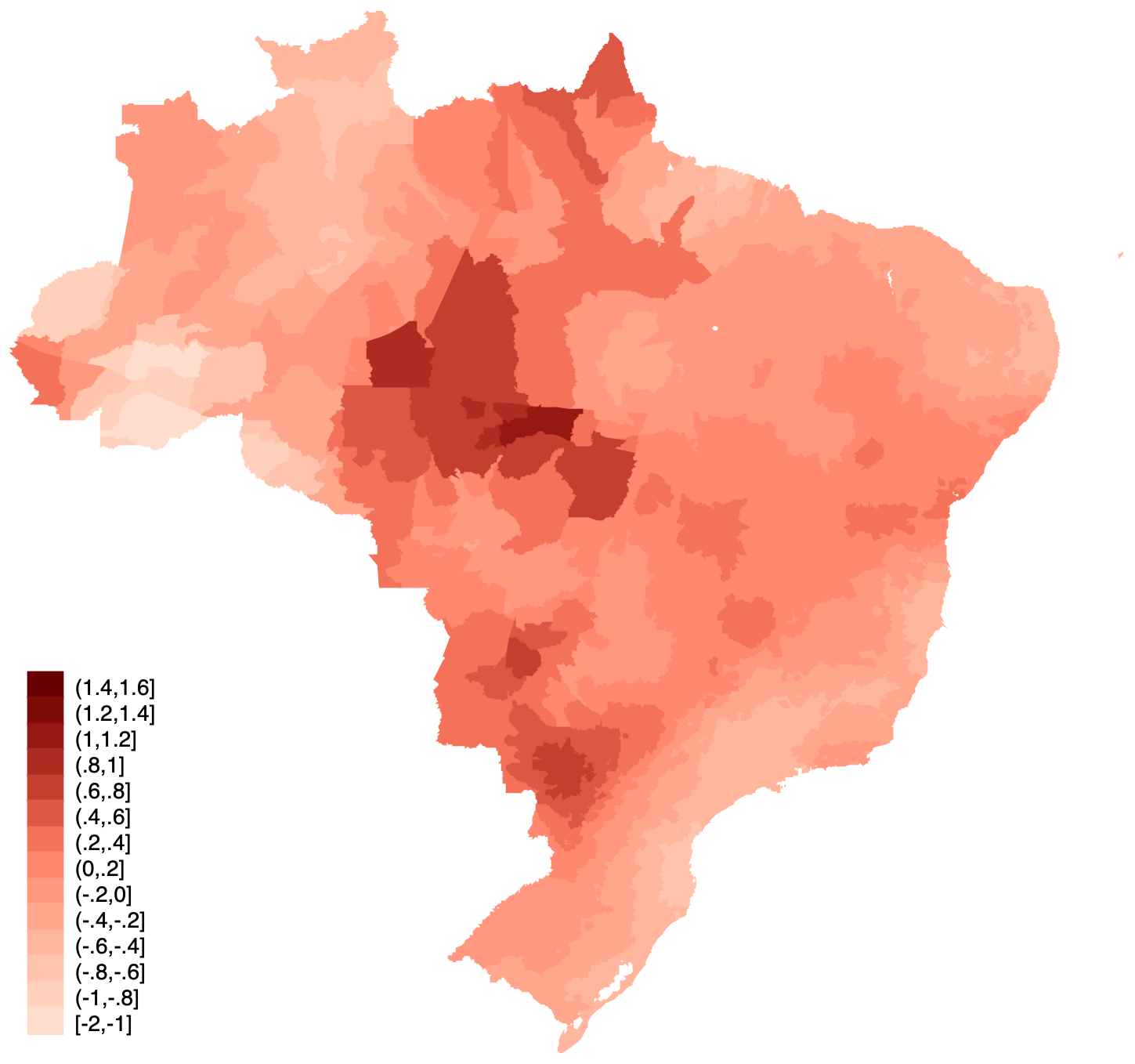

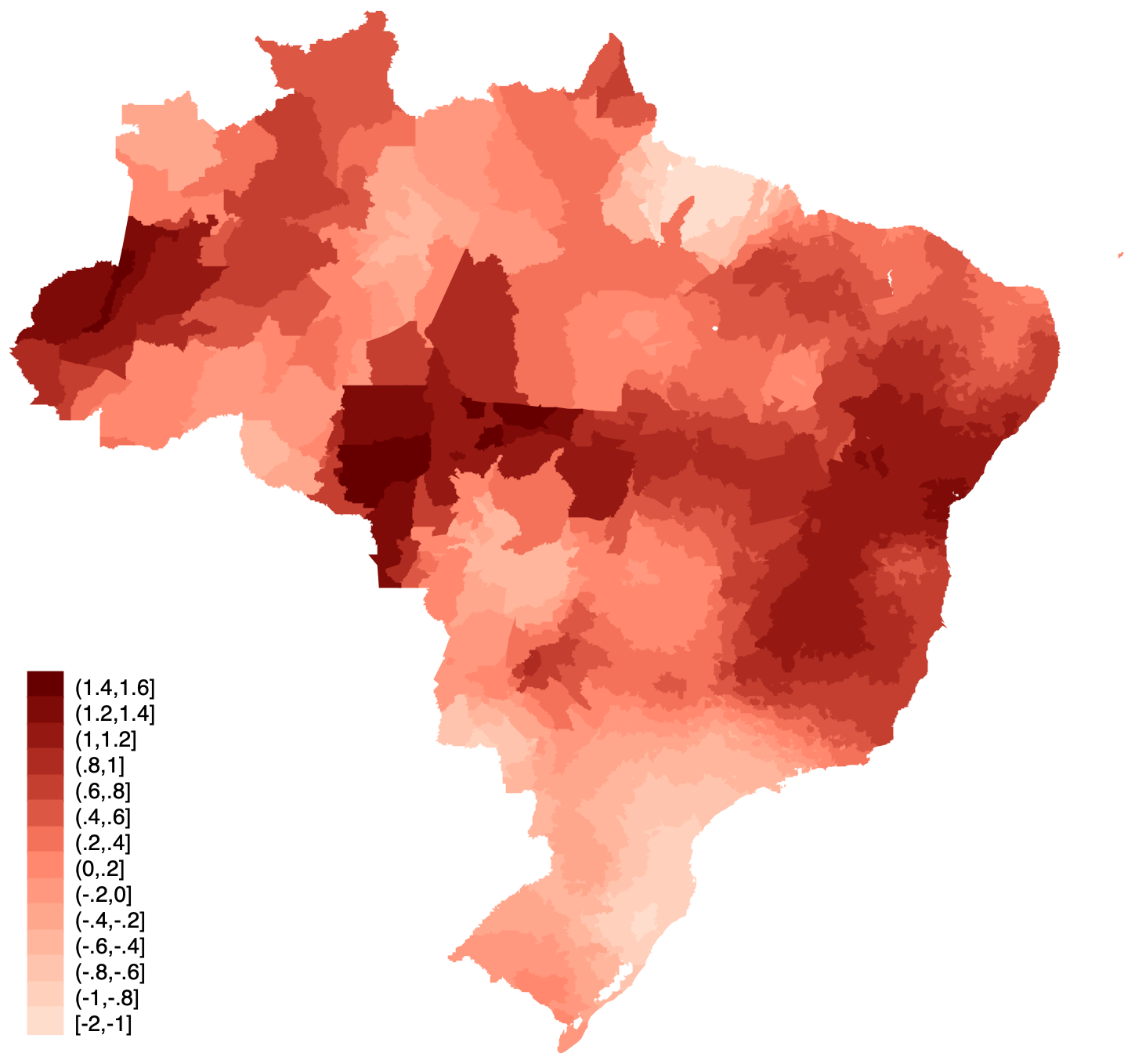

Figure 1 shows the number of natural disasters reported to the federal government by municipalities since 2000. Droughts are the most frequent disaster, with 1,000 to 1,500 yearly reports during the 2000s and an increase to more than 2,000 during most years of the 2010s. We look at the SPEI, a measure of meteorological dryness capturing the moisture deficit in a given location relative to its long-run average based on precipitation and temperature. The SPEI also indicates a strong increase in dryness during the 2010s across major parts of Brazil (Figure 2).

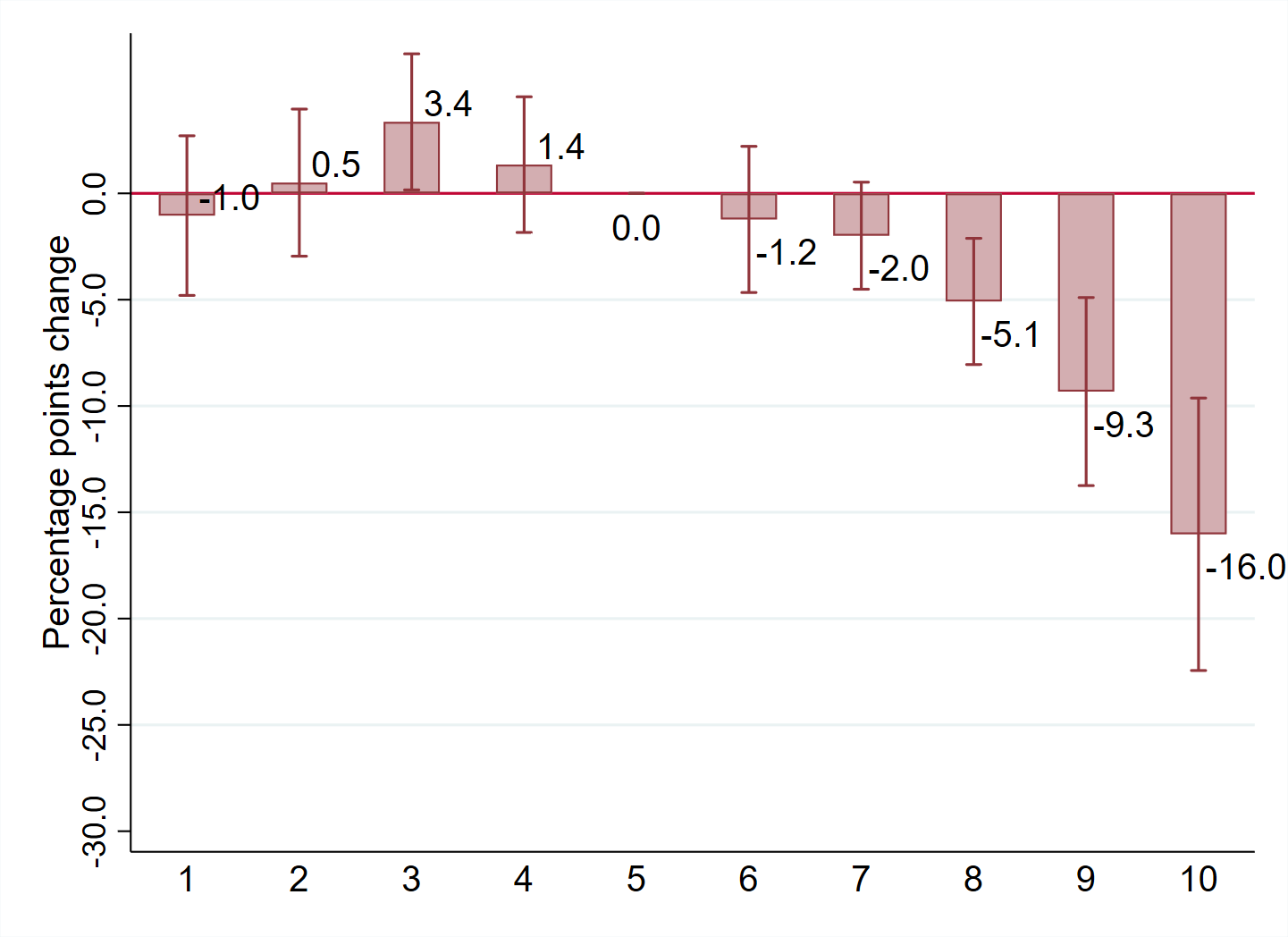

Higher dryness leads to sharp reductions in agricultural output. Municipalities in the top decile of the distribution of dryness in a given year suffer a loss of 16 per cent in the value of agricultural production relative to those in the middle of the distribution (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Reported natural disasters in Brazil: 2000-2018

Notes: Number of natural disasters by year. Source: SINPDEC.

Figure 2. Dryness relative to historical averages

(a) 2000-2010

(b) 2011-2018

Notes: Average SPEI-12 by municipality. We multiply SPEI-12 by -1 so that a higher number indicates higher dryness conditions. Source: Vicente-Serrano et al. (2010)

Figure 3. Decline in value of agricultural production by decile of dryness

Notes: Estimated coefficients on dummies capturing deciles of Dryness (SPEI-12 x -1). The omitted decile is 5th.

How does financial capital react to these productivity shocks? We find regions directly affected by excessive dryness in a given year to experience an expansion of loans, partly financed by municipalities connected to affected ones through the bank branch network. This indicates that regions are partially insured against dryness shocks in the short run through financial integration. However, in the long run, we observe capital outflows from affected areas, as lending is strongly reduced: a municipality at the 90th percentile of the distribution of the 2000-2010 average dryness index SPEI suffers a 10 per cent decline in lending relative to the median. This is consistent with (perceived) permanent negative effects of an unusually dry decade on local productivity.

We also investigate how dryness affects local labour markets and movements of people. We find a strong migration response to higher average dryness over a decade. Relative to the median, a municipality at the 90th percentile of dryness suffers a 1.4 per cent population loss, mainly driven by outmigration. On the other hand, regions linked through historical migration patterns to those affected by dryness expand through migrant inflows.

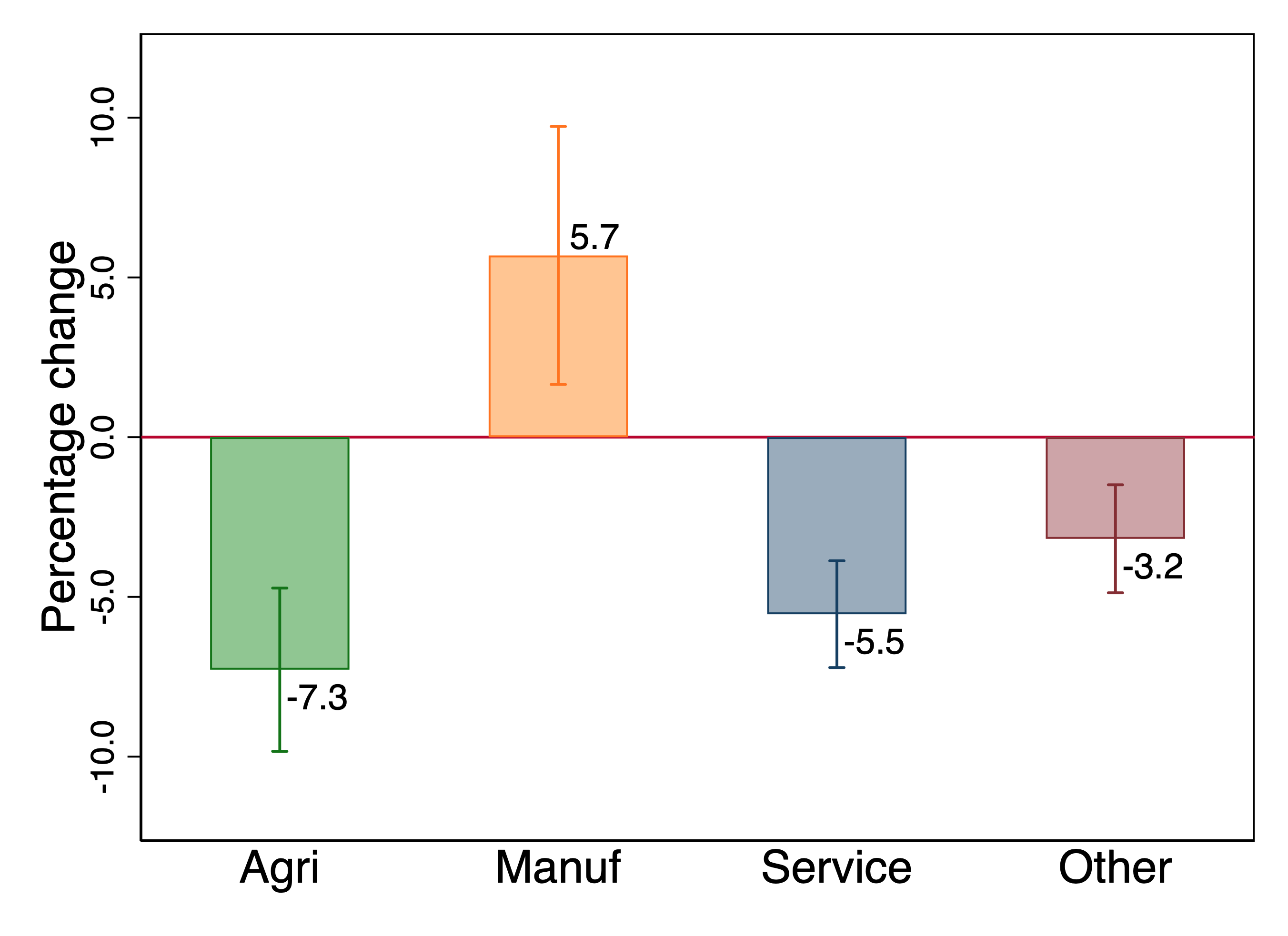

How do dryness shocks and resulting population movements affect sectoral employment? Areas with a higher incidence of droughts experience a sharp decline in employment in the agriculture and service sectors and an increase in manufacturing (Figure 4a). This suggests that lower agricultural productivity reduced the demand for local non-traded good (services), while it generated an expansion in local traded goods (manufacturing) by decreasing the price of labour.

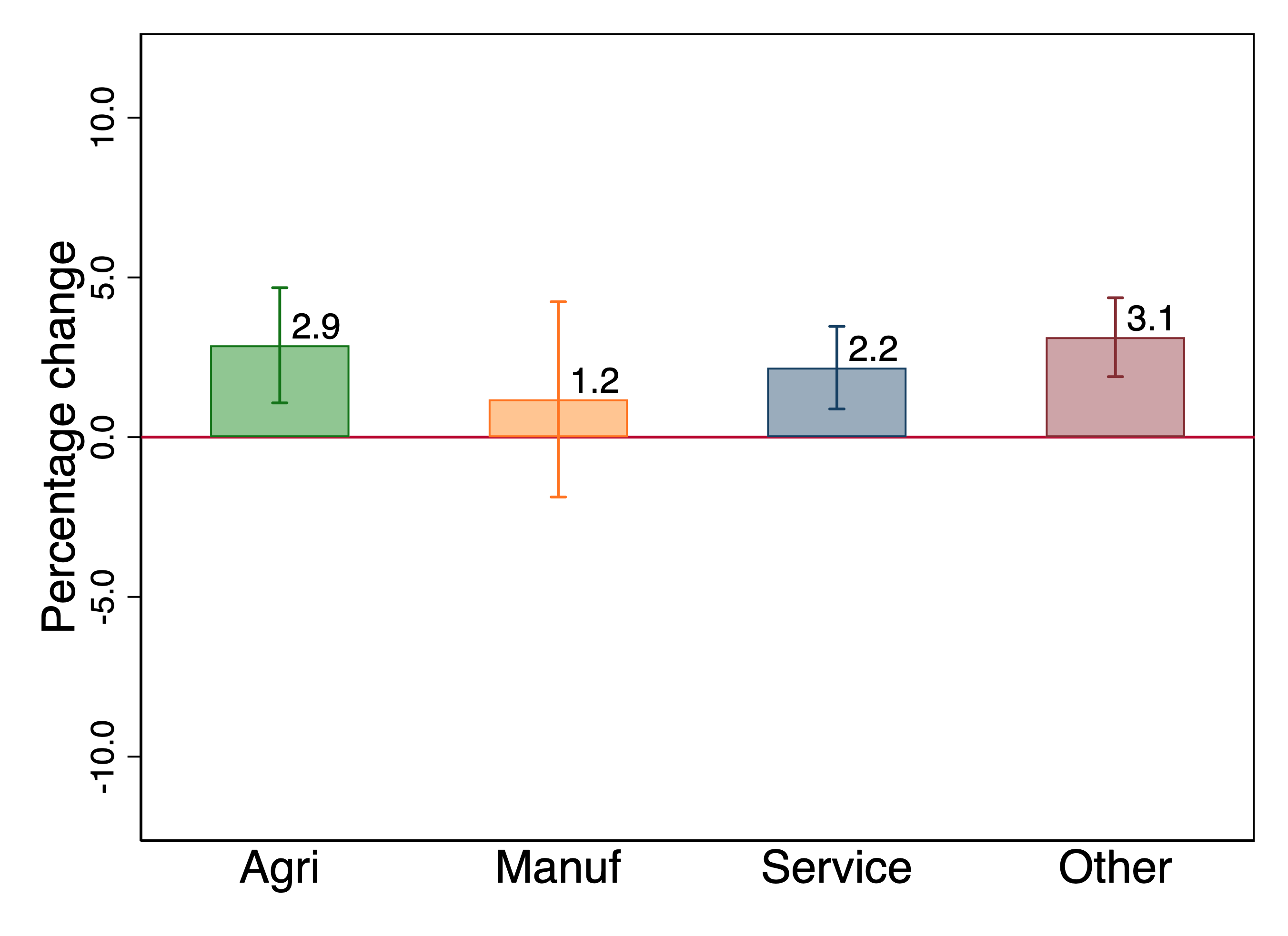

Still, only a quarter of the workers that leave agriculture and services find jobs in local manufacturing, while about half emigrate to other municipalities. The remainder becomes unemployed or is not fully captured in the migration data. In contrast, as seen in Figure 4b, regions that receive climate migrants see their employment expand in agriculture and services, but not in manufacturing.

Figure 4. Dryness and sectoral composition of the economy

(a) direct effects on affected municipalities

(b) indirect effects on connected municipalities

Notes: Estimated effects on employment by sector between 2000 and 2010 for a municipality going from the 50th to the 90th percentile in the direct and indirect (exposure via migrant network) measures of excess dryness.

Notes: Estimated effects on employment by sector between 2000 and 2010 for a municipality going from the 50th to the 90th percentile in the direct and indirect (exposure via migrant network) measures of excess dryness.

To understand the employment trajectories of workers leaving regions affected by dryness, we employ social security data covering all formal workers in Brazil. This allows us to trace worker movements across regions and sectors over time.

Workers from excessively dry areas tend to reallocate towards firms with already larger shares of employees from their same origin, possibly thanks to referrals. This implies that climate migrants do not amount to a symmetric increase in labour supply for all firms. Instead, labour market frictions direct migrants to connected firms. This has important implications for the composition of economic activity in destination regions.

The manufacturing sector is the least connected to areas exposed to excess dryness through past migrant networks: only 2 per cent of its workers come from those areas compared to 4 per cent in services and 6 per cent in agriculture. This might reflect the fact that manufacturing is more geographically concentrated due to agglomeration economies. Even in the presence of referral networks, manufacturing firms are less prone to employ workers from dry areas, potentially because they require specialised skills sourced in thick local labour markets.

Overall, our work helps us understand the economic effects of climate change. Long periods of excess dryness relative to historical averages generate reallocation of capital and labour away from affected regions, consistent with a permanent reduction in agricultural productivity and limited capability of adaptation. Excess dryness changes the structure of the economy in both directly affected areas and those integrated via labour and capital markets.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on The Effects of Climate Change on Labor and Capital Reallocation, presented at LSE’s Environment Week (September 2022).

- The post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Bruno Souza on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.