The crisis has resulted in a substantial rise in unemployment in Europe and a notable divergence in unemployment rates and labour market outcomes post-crisis. Particularly, the events that unfolded since the financial crisis and the ensuing sovereign debt — as well as political and institutional — crisis had a tremendous impact on labour markets across Europe. Following a period of subsiding unemployment since 2004, unemployment rose sharply after 2008, rising from just below 7 per cent in 2008 to 9.7 per cent in 2010 and to near 11 per cent in 2013; in some countries, unemployment reached historically unprecedented levels – e.g., above 25 per cent in Spain and Greece.

While at the EU level unemployment today seems to have returned close to its pre-crisis trough, unemployment levels remain exceptionally high in a large pool of countries. A rich and diverse literature emerged, following these developments, that sought to examine the dynamics governing unemployment change in Europe during this turbulent period. This included macroeconomic studies examining shifts in the Phillips Curve (Bulligan and Viviano, 2017) and in the responsiveness of unemployment to changes in output (Cazes et al., 2013), studies examining the individual drivers of unemployment and of youth unemployment in particular (Carcillo et al., 2013; Eichhorst and Neder, 2014; Mauro and Mitra, 2015; Dolado et al., 2013; Kelly and McGuinness, 2015), as well as a limited number of studies examining labour market transitions, and the inflows and outflows from unemployment in particular (Ward-Warmedinger and Macchiarelli, 2014; Daouli et al., 2015; Macchiarelli et al., 2018).

Adding to this literature, in a recent study we implemented a detailed and comparative investigation of the dynamics characterising labour market transitions across Europe during this period, focusing on examining the transition dynamics exhibited in European labour markets during the episodes of crisis and recovery. Labour market transitions show the movements of individuals between the labour market statuses of employment, unemployment and economic inactivity. Our study, forthcoming in Campos, De Grauwe and Ji (2020) drew on earlier work we undertook for the Social Situation Monitor of the European Commission (Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs).

Our analysis covers the period prior to the crisis (2004/2008) and up to 2016. For much of the analysis, we focus on three sub-periods, i.e. between 2004/08, 2009/13 and 2014/16. Drawing on the EU Labour Force Survey statistics (EU-LFS), we examined individuals’ transitions across labour market statuses. For the discussion and further analysis of the results, we finally complement these data with qualitative and macro-quantitative information from the OECD about the different countries of the EU, allowing us to split the countries into different groupings corresponding to different social systems.

More specifically, we analysed labour market transitions, both year-on-year and cumulatively for the period under consideration, across the three key labour market statuses of employment, unemployment and inactivity, providing aggregate break-downs by country, age-groups, gender and individual’s level of education based on the EU-LFS. Following this, we developed country-specific measures of transition rates and a synthetic index of mobility in order to draw comparisons across countries and over time. We looked both at individual countries and at country groups, classifying the EU countries into four groups of Mediterranean, Continental, Central Eastern and Nordic. This offered a granular overview of labour market trends by country and for the EU as a whole, allowing us to draw conclusions about the functioning of labour markets in Europe with regard to their flexibility (speed/extent of transitions and extent of mobility/churn) and how this evolved over time. A focus on the behaviour of labour market transitions around periods in which actual unemployment has risen or fallen sharply may inform on the factors behind shifting mobility flows, as well as other factors contributing to periods of prolonged economic slowdown and/or unemployment persistence (i.e. hysteresis).

Our analysis shows that all EU country groups (Mediterranean, Continental, Central-Eastern, Nordic) exhibit a high degree of employment persistence and persistence of inactivity (out of the labour force), which shows little cyclicality. The dynamics concerning unemployment duration, however, appear more varied. Our evidence shows that unemployment persistence is by far highest in the Nordic countries and lowest, post-crisis, in the Mediterranean. Unemployment persistence increased with the crisis everywhere, and except for the Central and Eastern European countries, it continued to rise also after 2012.

Disaggregating these patterns on the basis of individual characteristics, revealed that individual heterogeneity plays a role, with male and highly educated workers experiencing more favourable transitions from unemployment into employment on the whole (including during the crisis period), although this was stronger in some groups (e.g., Nordics) than others (e.g., the Mediterranean). Amongst all groups and periods, age seemed to be the main factor accounting for the largest differences in labour market transitions. Concerning the case of unemployment persistence, for example, this was found to be higher for young individuals (16-24 and 25-29 years old) in the Nordics, well above any other category; more mature workers in the Continental countries (30-54 years old); and the 25-29 year olds in the Mediterranean and in Central and Eastern Europe. Inversely, overall mobility was found to be higher – and increasing with the crisis – for people below 54 and for highly educated people in Continental countries; by younger individuals and again for the highly educated in Central and Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean; and highest for the 16-24 year olds – but not for the highly educated – in the Nordics.

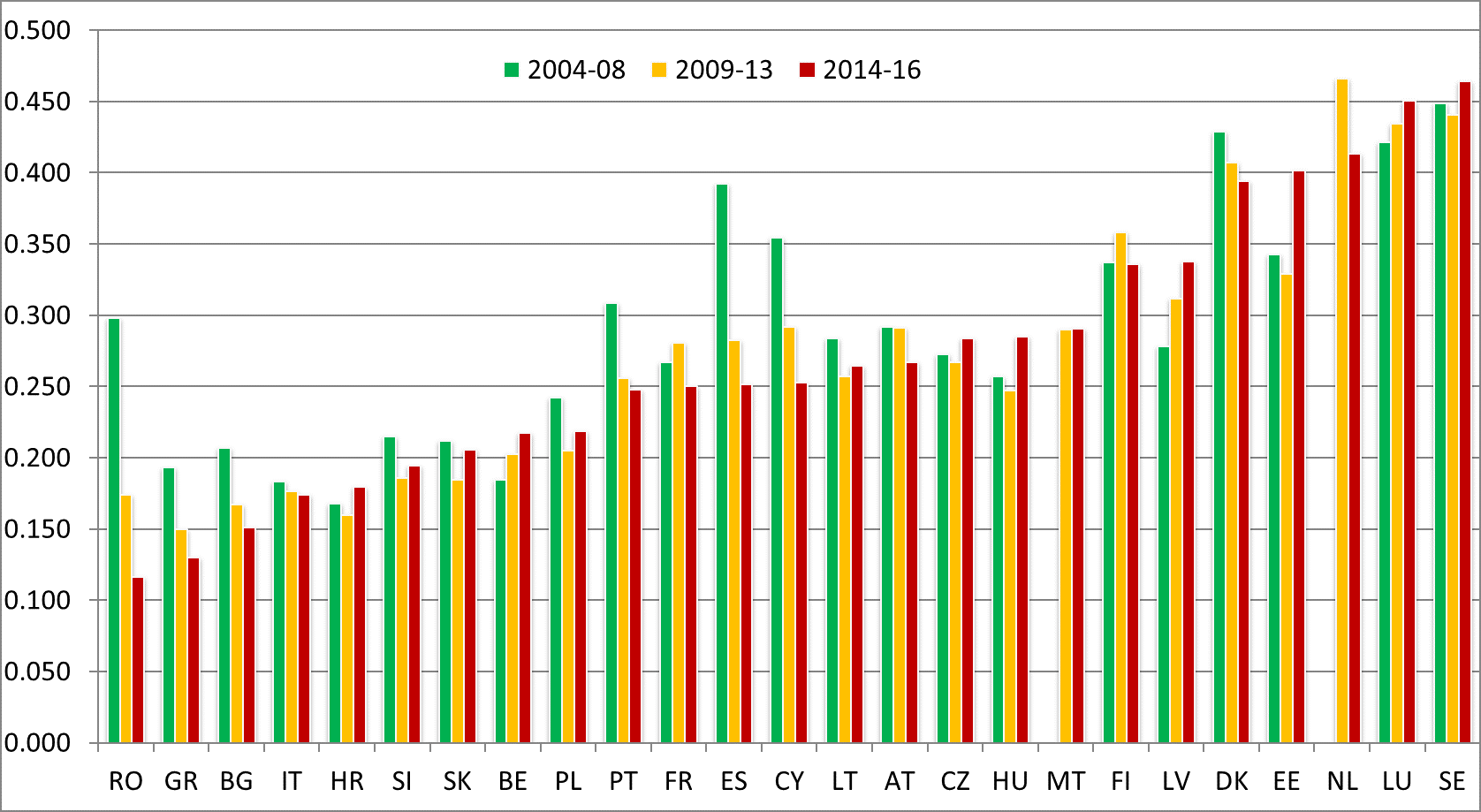

Figure 1 provides a summary picture of our measure for labour market mobility. Importantly, the index interprets the frequencies at which individuals change their labour market status – which is, inversely, the persistence of specific labour market outcomes at the individual level – as a proxy for labour market “fluidity”.

Figure 1: Mobility index in the EU

Sources: EU-LFS microdata, authors’ computations

The mobility index reflects an increase in labour market churning over the crisis period in Nordic and Continental countries. On the contrary, the mobility index for the period 2009-13 reveals a decrease in labour market mobility compared to the pre-crisis both in the Mediterranean and the Central Eastern European countries. The drop in mobility since the crisis may suggest a less efficient matching of individuals with jobs, as evidenced by the increase in the probability to remain in unemployment. [i] For Mediterranean countries, lower mobility over time analogously reflects an increase in the likelihood to remain unemployed over time. In the Nordic and Continental countries, mobility increased over the crisis period, essentially as the result of a fall in the probability of remaining in employment, unemployment and inactivity.

Looking at the results in the figure, labour markets in Spain, the Netherlands, Estonia and Luxembourg, together with Finland, Denmark and Sweden, are more flexible on average. For the latter mobility is twice as high relative to Greece, Bulgaria, the Slovak Republic, Poland, Latvia, Hungary, Croatia, Italy, Belgium, and Slovenia. A group of countries reporting intermediate mobility is represented instead by the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Austria, France, Cyprus and Portugal. Spain, Cyprus and Romania recorded the highest drops in mobility since the crisis.

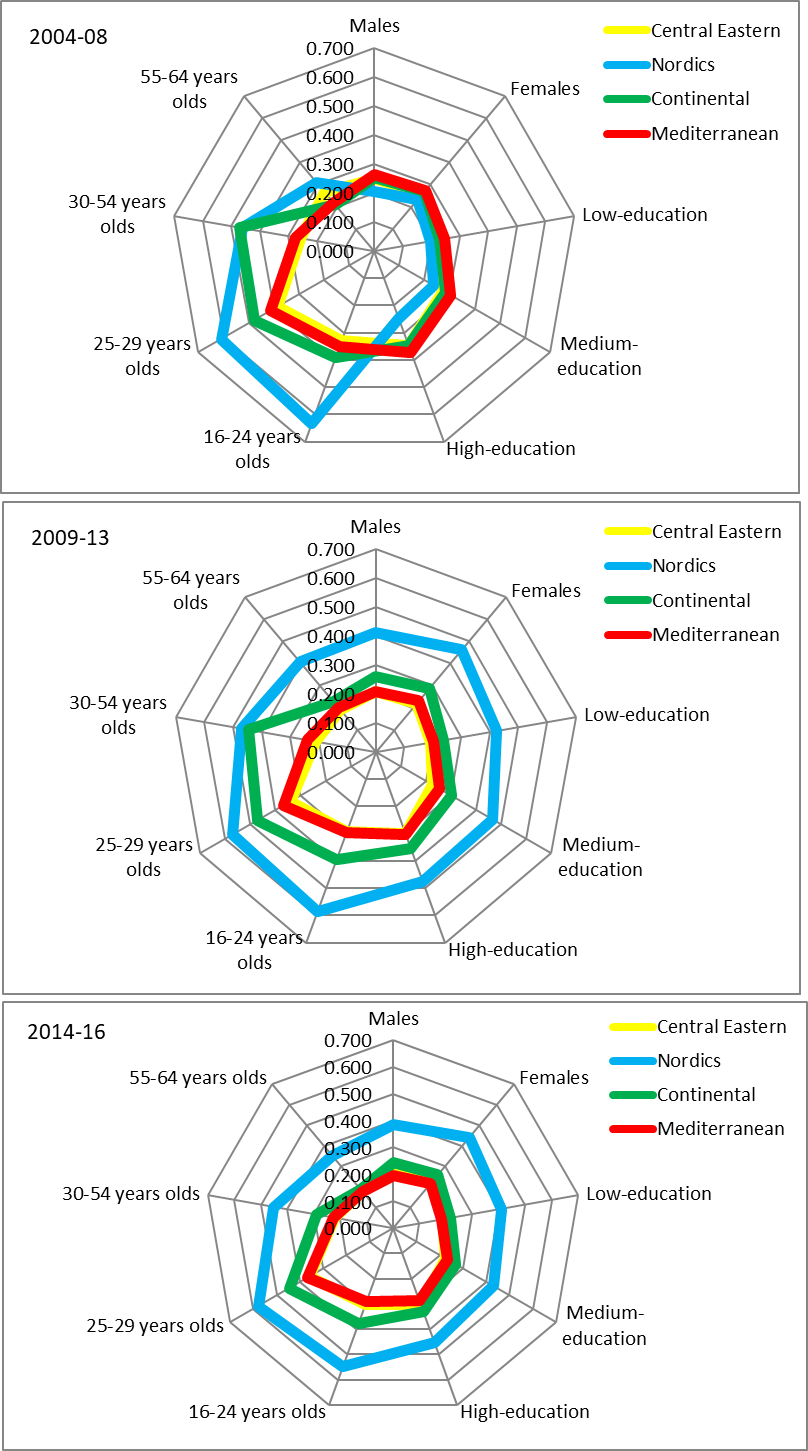

Breaking down the results by individual characteristics and across time (Figure 2), the mobility index confirms that, in Continental countries, mobility was particularly high for people below 54 and highly educated people, and has overall increased over the crisis, as the result of a lower likelihood to remain in employment, unemployment and inactivity. From Figure 2, in Nordic countries, people between the ages of 16-24 are the most mobile on average albeit their mobility has decreased over time, particularly during the crisis. Such behaviour is always driven by a lower probability of remaining in employment, unemployment and inactivity compared to Continental and Mediterranean countries.

In Nordic countries, highly educated individuals generally display both a higher probability of remaining in employment and a lower probability of remaining in unemployment and inactivity over time, while female workers display a lower probability of remaining in both employment and unemployment over time [ii].

In Central Eastern European countries mobility is higher for females, highly educated people and workers between the ages of 25 and 29, though this pattern has overall decreased over time. In these countries, the higher mobility of women is driven by a lower probability of remaining in employment and unemployment over time. Highly educated individuals in the Central Eastern EU countries are more mobile through a lower probability over time of remaining in inactivity and unemployment.

Figure 2 also shows that on average highly educated individuals and people between the ages of 25-29 are the most mobiles across labour market statuses. Moreover, for Denmark, Sweden, the Continental and Mediterranean counties mobility of all worker groups has increased over the last decade – particularly for female workers.

Our descriptive analysis finally concentrates on the relationship between labour market mobility and various labour markets institutions, such as part-time contracts, product market regulation, employment protection legislation, and employment incentives. We find that mobility is on the whole inversely related to the degree of product market regulation, positively related to the prevalence of part-time contracts and employment incentives schemes, but has no relation with the degree of employment protection in the labour market.

Figure 2: Mobility index by worker group

Sources: EU-LFS microdata, authors’ computations

Overall, our results sketch a picture of significant country heterogeneity in the intensity and direction of labour market transitions across the EU. As expected, the crisis did have an impact on labour market transitions and employment/unemployment persistence, but in most cases, the effect of the crisis was smaller than the size of country differences observed in any one period (pre-crisis, during the crisis and post-crisis). Countries known for their institutional rigidities in the labour market, such as those of the Mediterranean, have been found to have less favourable labour market transitions and higher unemployment persistence. At the same time, we found no evidence that this links directly to the degree of employment protection, the main labour market institution associated with labour market rigidity. Instead, part-time employment seems to have played a – rather marginally – positive role for containing unemployment persistence, while product market regulations appear as a much more significant influence on adverse labour market transitions (and lower labour market mobility in particular). In any case, and despite the relative recovery of the European economies post-crisis, the degree of labour market flexibility (and the rates of labour market transitions) has not fully recovered to their pre-crisis levels, especially in some countries.

Drawing on these results, we conclude that efforts to increase labour market ‘fluidity’ should continue: unemployment persistence remains high in much of the EU post-crisis, while labour market transitions are not equally ‘fluid’ in all countries or for all groups of workers. Enhancing this fluidity in the labour market, and especially facilitating convergence across countries in their extent of unemployment persistence, labour market churn or transitions into employment, does not seem to be conditioned on raising labour market flexibility in the traditional sense (namely, reducing employment protection). Rather, policy should aim at more nuanced and country/context-specific measures, including ones that fall outside the labour market.

[i] Mobility clearly depends on the level of unemployment. In a country with high employment you would also expect low mobility between states (as those not in employment are probably really those with the least attractive characteristics). This interpretation is different for a country with low employment as it could point to rigidities or disincentives to work. Note also that high transitions should not necessary be good, as in a highly segmented labour market dominated by short term contracts, this may mean that individuals regularly switch between employment and unemployment (e.g. Spain or France).

[ii] It should be noted, however, that successful exits of females from unemployment into employment are typically lower than those of males. This is because females also have a higher probability of moving from unemployment into inactivity compared to males.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ chapter, which is forthcoming in N. Campos, P. De Grauwe and Y. Ji (eds.), Structural Reforms and Economic Growth in Europe, Cambridge University Press.

- The post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by StockSnap, under a Pixabay licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Corrado Macchiarelli is a senior lecturer in economics and finance at Brunel University London and a visiting fellow at LSE’s European Institute. Beyond his academic endeavours, he worked at the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund and consulted for the European Central Bank, the Swedish Riksbank, and the European Parliament. His interests lie mainly in the fields of international macro and finance, business cycles, and European economic governance. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Torino (Collegio Carlo Alberto).

Corrado Macchiarelli is a senior lecturer in economics and finance at Brunel University London and a visiting fellow at LSE’s European Institute. Beyond his academic endeavours, he worked at the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund and consulted for the European Central Bank, the Swedish Riksbank, and the European Parliament. His interests lie mainly in the fields of international macro and finance, business cycles, and European economic governance. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Torino (Collegio Carlo Alberto).

Vassilis Monastiriotis is an associate professor of political economy at LSE’s European Institute. He is director of LSE’s research unit on Southeast Europe and holds affiliations with LSE’s department of geography and the Hellenic Observatory. His research focuses on economic policy and performance at the regional, national and supra-national levels, with emphasis on labour markets, education and economic growth. Geographically his research specialises in Southeast Europe and the European Union. He has published numerous articles in economics and regional science journals, has strong media and consultancy experience, and has received various distinctions including the Moss Madden Medal in Regional Science (2008). He has a PhD in economic geography and MSc and BSc degrees in economics. He is co-editor of Spatial Economic Analysis (Taylor & Francis).

Vassilis Monastiriotis is an associate professor of political economy at LSE’s European Institute. He is director of LSE’s research unit on Southeast Europe and holds affiliations with LSE’s department of geography and the Hellenic Observatory. His research focuses on economic policy and performance at the regional, national and supra-national levels, with emphasis on labour markets, education and economic growth. Geographically his research specialises in Southeast Europe and the European Union. He has published numerous articles in economics and regional science journals, has strong media and consultancy experience, and has received various distinctions including the Moss Madden Medal in Regional Science (2008). He has a PhD in economic geography and MSc and BSc degrees in economics. He is co-editor of Spatial Economic Analysis (Taylor & Francis).

Nikolitsa Lampropoulou holds a PhD in economics from the University of Patras. She works as a customs officer for the Independent Authority for Public Revenue in Greece. She was previously a Hellenic Bank Association postdoctoral fellow at the Hellenic Observatory, LSE’s European Institute. She has also taught at the department of economics at LSE and the University of Patras. Her research interests lie in the fields of labour economics, applied microeconometrics, unemployment, labour mobility, discrimination and migration. She has also participated in several research projects such as the “Social Situation Monitor” for the European Commission, and “Unemployment Duration in Greece” for the University of Patras.

Nikolitsa Lampropoulou holds a PhD in economics from the University of Patras. She works as a customs officer for the Independent Authority for Public Revenue in Greece. She was previously a Hellenic Bank Association postdoctoral fellow at the Hellenic Observatory, LSE’s European Institute. She has also taught at the department of economics at LSE and the University of Patras. Her research interests lie in the fields of labour economics, applied microeconometrics, unemployment, labour mobility, discrimination and migration. She has also participated in several research projects such as the “Social Situation Monitor” for the European Commission, and “Unemployment Duration in Greece” for the University of Patras.