The UK has seen slow rates of productivity growth over the past decade, with output per hour and real wages no higher today than they were prior to the global financial crisis. The February 2020 Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) survey asked its panel of top UK economists about the causes of and possible policy responses to slow growth in UK productivity. Respondents were first asked for the (two) main causes for low productivity growth. They were then asked to give their (two) preferred policy options.

Nearly half of the economists surveyed point to low demand due to the financial crisis, austerity policies and Brexit as a major cause for this productivity slowdown. Despite this diagnosis, only a small minority of the panel believes that the solution lies in demand-side policy. Instead, a majority of panellists support promoting productivity growth through investments in education and worker training. Other policies such as infrastructure investments, and tax and regulatory policies are also proposed.

Productivity puzzle

Growth of output per worker has declined dramatically since the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Output per hour and real wages are now no higher than they were prior to the financial crisis. Output per hour decreased during the last two quarters of 2018 and the first two quarters of 2019.

While the United States and other advanced economies have also experienced productivity slowdowns, the UK slowdown has been more dramatic with the UK ranking 31st out of 35 OECD countries in growth of output per hour from 2008 to 2017. This is despite the fact that the UK is near the top of the league table for ICT-intensive employment, where productivity growth has been the strongest.

One study finds that the productivity slowdown has been relatively widespread, while another has suggested that it was confined largely to two sectors: finance and manufacturing. A third suggests that the slowdown is driven by firms at the top of the productivity distribution: these remain the firms with the fastest productivity growth, but they have seen a relatively greater growth deceleration.

There have been two broad categories of explanations for the productivity slowdown. The first focuses on supply-side factors. This category includes employee skills, with the UK among the worst in Europe in terms of mismatch between skills and field of employment, sluggish investment in research and development (R&D), and global factors, including increases in market power. One study suggests greater labour market flexibility in the UK than in other major economies as an explanation.

The second category of explanations focuses on demand-side factors, implicating the financial crisis, austerity and other causes for slow demand growth in the past decade. There is a separate, longer-term UK productivity puzzle. UK output per hour has underperformed its G7 peers for several decades. The recent slowdown may be affected by these longer-term trends, but the focus of this survey is on the performance of the UK economy in the past decade.

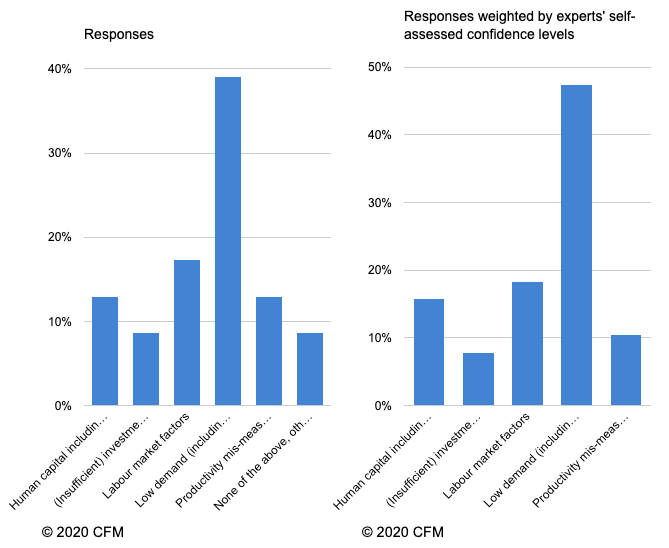

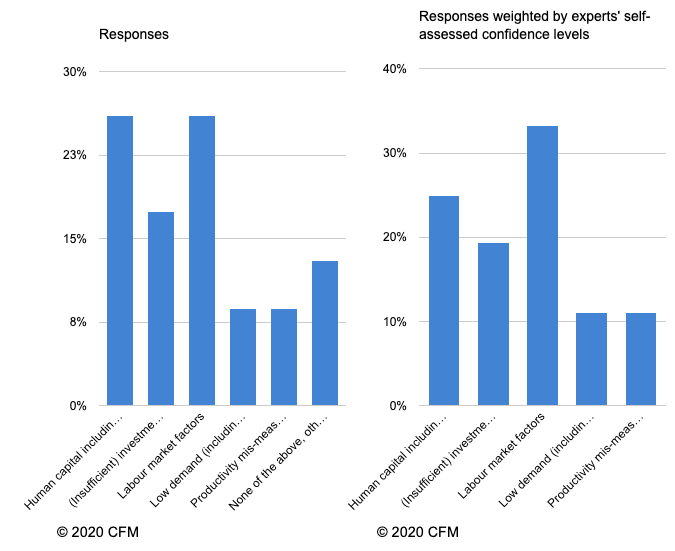

Related to this debate, the first two questions in the latest CFM survey asked panellists for the two most important causes of the productivity slowdown:

Q1. Which was the most important cause for the slowdown in UK productivity growth?

Q2. Which was the second most important cause for the slowdown in UK productivity growth?

Twenty-three panellists responded to these questions. Nearly half of the respondents list low demand as a factor driving low productivity growth in the past decade, with 40% of respondents listing this factor as the most important cause. The share is even larger when responses are weighted by respondents’ degree of confidence.

Respondents pointed to a variety of causes for low demand and productivity, as a result. David Cobham (Heriot-Watt University) suggests that ‘low demand is mainly down to austerity, a misconceived strategy… whose defects have been highlighted by both academics and the research department of the IMF.’ Nicholas Oulton (LSE) points to Brexit and ‘the slowdown after 2007 in demand for UK exports concentrated as they are on the EU’.

Wendy Carlin (University College London) explains the channels through which demand factors may affect productivity: ‘Productivity improvements depend on R&D and on business investment… Both are depressed by low expectations of future market growth, which has been the case since the crisis.’

A large number (43%) of respondents also point to labour market factors as a drag on productivity, with 17% listing this as the main factor impeding productivity growth. An additional 39% of respondents point to the related issue of workers’ skills (with 13% listing this as the primary cause).

Chryssi Giannitsarou (Cambridge University) notes that in an accounting sense, the drop in productivity can be largely accounted for with the increase in employment rates. ‘Therefore labour market factors need to be understood better: for example, demand for new forms of labour types and skills in the last 10-15 years, particularly in the sector of services.’ Kate Barker (British Coal Staff Superannuation) points to the loss in workers’ bargaining power and the ‘erosion for some young people of a skills premium’.

Francesca Monti (King’s College London) put workers’ skills and the mismatch between worker skills and skills needed by employers as central to the productivity decline. Thorsten Beck (Cass Business School) attributes the skill mismatch to a ‘missing middle’ in the UK educational system, which focuses on either academic education or basic skills for low-skilled workers. He remarks that ‘there is a need for a strong technical education system with apprenticeships as, for example, in Germany’.

Some respondents question whether productivity was accurately measured or whether the slowdown was a uniquely UK phenomenon. Patrick Minford (Cardiff Business School) notes that the ICT sector is the engine of UK growth and productivity measurement is particularly challenging in this sector. He states that ‘I certainly find it odd to see widespread pessimism over productivity trends co-existing with equally widespread concerns over the job-destroying effects of ICT.’

Charles Bean (LSE) suggests that ‘we should focus on common, rather than the UK-specific, factors,’ because the slowdown was common across developed nations and pre-dated the financial crisis in the United States. He points, however, to a decline in business dynamism and increased concentration in some markets.

Policy solutions

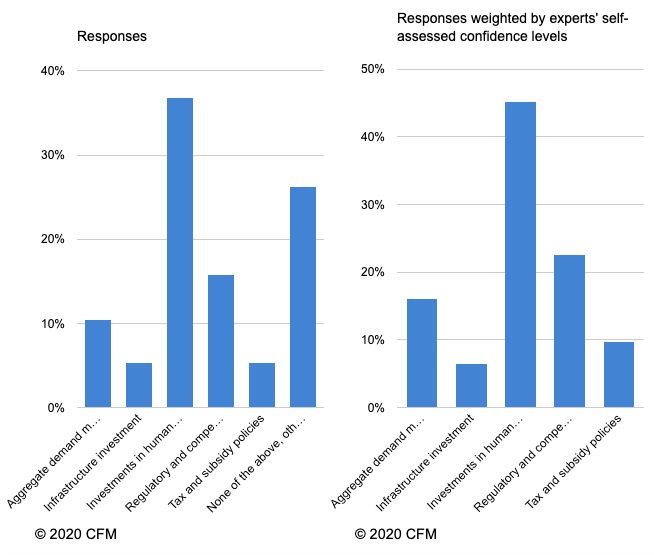

With the majority of respondents agreeing that the productivity growth slowdown is more than a statistical artefact, we asked the panel for their policy recommendations to boost UK productivity. Each panel member was allowed to select two policies:

Q3. Which policy would best help improve private sector productivity?

Q4. Which policy would be your second choice of policy to boost private sector productivity, in addition to or absent your first choice?

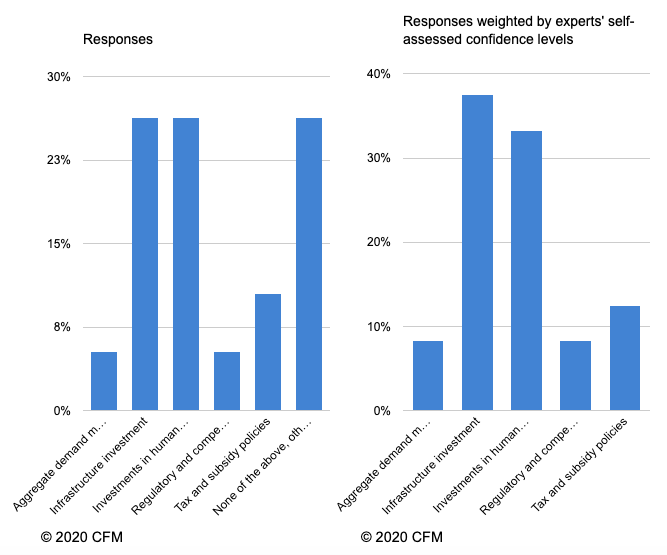

Interestingly, although a plurality of panel members see muted demand as the primary cause for the UK productivity puzzle, only a small fraction (16%) of respondents view aggregate demand management as part of the solution.

Instead, more than half of respondents (63%) propose investments in human capital, such as education and job retraining, as a policy solution. 37% of respondents choose this as the best policy and the remainder as a secondary policy. The share of respondents supporting this view is larger when weighing responses by their degree of confidence.

Thorsten Beck notes that ‘improvements in technical skills would be a long-term solution to support a well-trained working population and thus also improve productivity growth.’ Panicos Demetriades (University of Leicester) makes the caveat that investment in education ‘is the most direct way to improve skills and human capital once we first ensure that the best talent isn’t diverted into unproductive activities and speculation.’

Charles Bean doesn’t view human capital as a major drag on productivity, but nevertheless suggests that it may be ‘a key factor behind the UK’s pre-existing lagging productivity performance’, well pre-dating the recent decade.

A number of respondents relate skills and education to immigration. On the one hand, Ricardo Reis (LSE) proposes that ‘if fewer high-skilled immigrants want to make the UK its home, the country will have to step up significantly the investment in its universities.’ On the other hand, Nicholas Oulton suggests that cuts in unskilled immigration could boost productivity as it would induce firms to increase capital investments.

A substantial share (32%) of respondents support infrastructure investments to boost productivity, with 5% selecting this as their preferred policy solution. Relatedly, a number of panellists suggest that regional investment policies could be part of the policy solution.

Respondents differ in the particular investments they support and several warn that some public investments might be wasteful. Nicholas Oulton warns that public investments may crowd out private investments. David Miles (Imperial College London) supports infrastructure investment to link cities to surrounding areas but suggests that ‘Britain’s biggest transport project – HS2 – seems an extraordinarily expensive and inefficient way of achieving this.’

Other proposals point to tax and regulatory policies, including diversion of resources to the zero-carbon transition (Wendy Carlin), improving business dynamism (Ricardo Reis), and ensuring that the nation’s greatest talents aren’t sucked into the financial sector (Panicos Demetriades).

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared first on the site of the Centre for Macroeconomics’ (CFM) website. It’s based on their latest survey.

- The post expresses the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Science in HD on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Ethan Ilzetzki is a lecturer in economics at LSE. He is an associate at the Centre for Macroeconomics and the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). His research interests are in macroeconomics, international finance and fiscal policy. He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Maryland.

Ethan Ilzetzki is a lecturer in economics at LSE. He is an associate at the Centre for Macroeconomics and the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). His research interests are in macroeconomics, international finance and fiscal policy. He holds a PhD in economics from the University of Maryland.